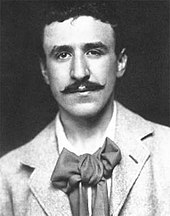

Charles Rennie Mackintosh

Charles Rennie Mackintosh (7 June 1868 – 10 December 1928) was a Scottish architect, designer, water colourist and artist. He was a designer in the Post-Impressionist movement and also the best known representative of Art Nouveau in the United Kingdom. He had considerable influence on European design. He was born in Glasgow and died in London.

Early life and education

Charles Rennie Mackintosh was born at 70 Parson Street, Townhead, Glasgow, on 7 June 1868, the fourth of 11 children[1] and second son of William McIntosh, the superintendent and chief clerk of the City of Glasgow Police, and his wife, Margaret Rennie. Mackintosh grew up in the Townhead and Dennistoun areas of Glasgow, and he attended Reid's Public School and the Allan Glen's Institution.[2][3]

In 1890 Mackintosh was the second winner of the Alexander Thomson Travelling Studentship, set up for the "furtherance of the study of ancient classic architecture, with special reference to the principles illustrated in Mr. Thomson's works."[4]

Name

He changed the spelling of his name from 'McIntosh' to 'Mackintosh' for unknown reasons, as his father did before him, around 1893.[5] Confusion continues to surround the use of his name with 'Rennie' sometimes incorrectly substituted for his first name of 'Charles'. The modern use of 'Rennie Mackintosh' as a surname is also incorrect and he was never known as such in his lifetime;[6] 'Rennie' being a middle name which he used often in writing his name. Signatures took various forms including 'C.R. Mackintosh' and 'Chas. R. Mackintosh.' His surname was thus 'Mackintosh'.

Career and family

Upon his return, he resumed work with the Honeyman and Keppie architectural practice where he started his first major architectural project, the Glasgow Herald Building (now known as The Lighthouse), in 1899. He was engaged to marry his employer's sister, Jessie Keppie.[7]

However, in 1892, Mackintosh met fellow artist Margaret MacDonald at the Glasgow School of Art. He and fellow student Herbert MacNair, also an apprentice at Honeyman and Keppie, were introduced to Margaret and her sister Frances MacDonald by the head of the Glasgow School of Art, Francis Henry Newbery, who thought that there were similarities in their work.[7] Margaret and Charles married on 22 August 1900.[8] The couple had no children. MacNair and Frances would also marry. The four companions would become known as the collaborative group "The Four", prominent members of the "Glasgow School" movement.

After completing several successful building designs, Mackintosh became an official partner in Honeyman and Keppie in 1904. When economic hardships were causing many architectural practices to close in 1913, he resigned from Honeyman and Keppie and attempted to open his own practice.

Design influences

Mackintosh lived most of his life in the city of Glasgow. Located on the banks of the River Clyde, during the Industrial Revolution, the city had one of the greatest production centres of heavy engineering and shipbuilding in the world. As the city grew and prospered, a faster response to the high demand for consumer goods and arts was necessary. Industrialized, mass-produced items started to gain popularity. Along with the Industrial Revolution, Asian style and emerging modernist ideas also influenced Mackintosh's designs. When the Japanese isolationist regime softened, they opened themselves to globalisation resulting in notable Japanese influence around the world. Glasgow's link with the eastern country became particularly close with shipyards building at the River Clyde being exposed to Japanese navy and training engineers. Japanese design became more accessible and gained great popularity. In fact, it became so popular and so incessantly appropriated and reproduced by Western artists, that the Western World's fascination and preoccupation with Japanese art gave rise to the new term, Japonism or Japonisme.

This style was admired by Mackintosh because of: its restraint and economy of means rather than ostentatious accumulation; its simple forms and natural materials rather than elaboration and artifice; the use of texture and light and shadow rather than pattern and ornament. In the old western style, furniture was seen as ornament that displayed the wealth of its owner and the value of the piece was established according to the length of time spent creating it. In the Japanese arts furniture and design focused on the quality of the space, which was meant to evoke a calming and organic feeling to the interior.

At the same time a new philosophy concerned with creating functional and practical design was emerging throughout Europe: the so-called "modernist ideas". The main concept of the Modernist movement was to develop innovative ideas and new technology: design concerned with the present and the future, rather than with history and tradition. Heavy ornamentation and inherited styles were discarded. Even though Mackintosh became known as the ‘pioneer’ of the movement, his designs were far removed from the bleak utilitarianism of Modernism. His concern was to build around the needs of people: people seen, not as masses, but as individuals who needed not a machine for living in but a work of art. Mackintosh took his inspiration from his Scottish upbringing and blended them with the flourish of Art Nouveau and the simplicity of Japanese forms.

While working in architecture, Charles Rennie Mackintosh developed his own style: a contrast between strong right angles and floral-inspired decorative motifs with subtle curves, e.g. the Mackintosh Rose motif, along with some references to traditional Scottish architecture. The project that helped make his international reputation was the Glasgow School of Art (1897–1909). During the early stages of the Glasgow School of Art Mackintosh also completed the Queen's Cross Church project in Maryhill, Glasgow. This is considered to be one of Charles Rennie Mackintosh most mysterious projects. It is the only church by the Glasgow born artist to be built and is now the Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society headquarters. Like his contemporary Frank Lloyd Wright, Mackintosh's architectural designs often included extensive specifications for the detailing, decoration, and furnishing of his buildings. The majority if not all of this detailing and significant contributions to his architectural drawings were designed and detailed by his wife Margaret Macdonald[9] whom Charles had met when they both attended the Glasgow School of Art. His work was shown at the Vienna Secession Exhibition in 1900. Mackintosh's architectural career was a relatively short one, but of significant quality and impact. All his major commissions were between 1895[10] and 1906,[11] including designs for private homes, commercial buildings, interior renovations and churches.

- Former Daily Record offices, Glasgow

- Former Glasgow Herald offices in Mitchell Street, now The Lighthouse – Scotland's Centre for Architecture, Design and the City

- 78 Derngate, Northampton (interior design and architectural remodelling for Wenman Joseph Bassett-Lowke, founder of Bassett-Lowke)

- 5 The Drive, Northampton (for Bassett-Lowke's brother-in-law)

Unbuilt designs

Although moderately popular (for a period) in his native Scotland, most of Mackintosh's more ambitious designs were not built. Designs for various buildings for the 1901 Glasgow International Exhibition were not constructed,[12] neither was his "Haus eines Kunstfreundes" (Art Lover's House) of the same year. He competed in the 1903 design competition for Liverpool Cathedral, but failed to gain a place on the shortlist[13] (the winner was Giles Gilbert Scott).

Other unbuilt Mackintosh designs include:

- Railway Terminus,

- Concert Hall,

- Alternative Concert Hall,

- Bar and Dining Room,

- Exhibition Hall

- Science and Art Museum

- Chapter House

The House for An Art Lover (1901) was built after his death in Bellahouston Park, Glasgow (1989–1996).[14]

An Artist's Cottage and Studio (1901),[15] known as The Artist's Cottage, was completed at Farr by Inverness in 1992. The architect was Robert Hamilton Macintyre acting for Dr and Mrs Peter Tovell.[16][17] Illustrations can be found on the RCAHMS Canmore site.[18]

The first of the unexecuted Gate Lodge, Auchinbothie (1901) sketches[19] was realised as a mirrored pair of gatehouses to either side of the Achnabechan[20] and The Artist's Cottage drives, also at Farr by Inverness. Known as North House and South House, these were completed 1995-7.[21][22]

Mackintosh's architectural output was small, but he did influence European design. Popular in Austria and Germany, his work received acclaim when it was shown at the Vienna Secession Exhibition in 1900. It was also exhibited in Budapest, Munich, Dresden, Venice and Moscow.

Design work and paintings

The Four

Mackintosh, his future wife Margaret MacDonald, her sister Frances MacDonald, and Herbert MacNair met at evening classes at the Glasgow School of Art (see above). They became known as a collaborative group, "The Four", or "The Glasgow Four", and were prominent members of the "Glasgow School" movement.[23] The group exhibited in Glasgow, London and Vienna, and these exhibitions helped establish Mackintosh's reputation. The so-called "Glasgow" style was exhibited in Europe and influenced the Viennese Art Nouveau movement known as Sezessionstil (in English, the Vienna Secession) around 1900. Mackintosh also worked in interior design, furniture, textiles and metalwork. Much of this work combines Mackintosh's own designs with those of his wife, whose flowing, floral style complemented his more formal, rectilinear work.

Later life

Later in life, disillusioned with architecture, Mackintosh worked largely as a watercolourist, painting numerous landscapes and flower studies (often in collaboration with Margaret, with whose style Mackintosh's own gradually converged). They moved to the Suffolk village of Walberswick in 1914. There Mackintosh was accused of being a German spy and briefly arrested in 1915.[24]

By 1923, the Mackintoshes had moved to Port-Vendres,[25] a Mediterranean coastal town in southern France with a warm climate that was a comparably cheaper location in which to live. Mackintosh had entirely abandoned architecture and design and concentrated on watercolour painting. He was interested in the relationships between man-made and naturally occurring landscapes, and created a large portfolio of architecture and landscape watercolour paintings. Many of his paintings depict Port Vendres, a small port near the Spanish border, and the landscapes of Roussillon. The local Charles Rennie Mackintosh Trail details his time in Port Vendres and shows the paintings and their locations.[26] The couple remained in France for two years, before being forced to return to London in 1927 due to illness.

That year, Charles Rennie Mackintosh was diagnosed with throat and tongue cancer. A brief recovery prompted him to leave the hospital and convalesce at home for a few months. Mackintosh was admitted to a nursing home where he died on 10 December 1928 at the age of 60. He was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium in London, his ashes are buried in the grounds (with a marker).

Retrospect

Mackintosh's designs gained in popularity in the decades following his death. His House for an Art Lover was built in Glasgow's Bellahouston Park in 1996, and the University of Glasgow (which owns most of his watercolour work) rebuilt the interior of a terraced house Mackintosh had designed, and furnished it with his and Margaret's work (it is part of the university's Hunterian Museum). The Glasgow School of Art building (now "The Mackintosh Building") is cited by architectural critics as among the finest buildings in the UK. On 23 May 2014 the building was ravaged by fire. The library was destroyed, but firefighters managed to save the rest of the building.[27]

The Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society encourages greater awareness of the work of Mackintosh as an architect, artist and designer. The rediscovery of Mackintosh as a significant figure in design has been attributed to the designation of Glasgow as European City of Culture in 1990,[28] and exhibition of his work which accompanied the year-long festival. His enduring popularity since has been fuelled by further exhibitions and books and memorabilia which have illustrated aspects of his life and work. The revival of public interest has led to the refurbishment and opening of more buildings to the public, such as the Willow Tea Rooms in Glasgow and 78 Derngate in Northampton. From the 1990s onwards the Scottish artist Stewart Bowman Johnson, who studied in the Mackintosh building at Glasgow School of Art, produced a series of interpretations of the architect's work including works depicting the doors and windows of the Willow tearooms.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City held a major retrospective exhibition of Charles Rennie Mackintosh's works from 21 November 1996 to 16 February 1997. In conjunction with the exhibit were lectures and a symposium by scholars, including Pamela Robertson of the Hunterian Art Gallery, Glasgow art gallery owner Roger Billcliffe, and architect J. Stewart Johnson, and screening of documentary films about Mackintosh.[29]

Charles Rennie Mackintosh was commemorated on a series of banknotes issued by the Clydesdale Bank in 2009; his image appeared on an issue of £100 notes.[30]

In 2012, one of the largest collections of art by Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the Glasgow Four Glasgow School was sold at auction in Edinburgh for £1.3m. The sale included work by Mackintosh's sister-in-law Frances Macdonald and her husband Herbert MacNair.[31]

In July 2015 it was announced that Mackintosh's designs for a tearoom would be reconstructed to form a display in Dundee's new V&A museum. Although the original building which housed the tearoom on Glasgow's Ingram Street was demolished in 1971 the interiors had all been dismantled and put into storage.[32]

See also

References

- ^ http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/architecture/11440936/Glasgow-School-of-Art-Charles-Rennie-Mackintosh-in-Exile.html

- ^ Edwards, Gareth (8 July 2005). "The many colours of Mackintosh – Scotsman.com News". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. Retrieved 14 September 2009.

- ^ "Dictionary of Scottish Architects – DSA Architect Biography Report (September vkfd;j14, 2009, 10:20 pm)". Retrieved 14 September 2009.

- ^ "The Alexander Thomson Memorial".

- ^ Kaplan, Wendy(ed.). Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Abbeville Press, 1996. ISBN 0-7892-0080-5. page 19.

- ^ Stamp, Gavin. Toshie Trashed, The London Review of Books, 19th June 2014. Pages 37-38.

- ^ a b Panther, Patricia (10 January 2011). "Margaret MacDonald: the talented other half of Charles Rennie Mackintosh". BBC Scotland. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ^ "MX.04 Interiors for 120 Mains Street" (PDF). Mackintosh Architecture : Context, Making and Meaning. University of Glasgos. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ^ "Margaret macdonald | Features | The Official Gateway to Scotland". Scotland.org. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ http://www.thelighthouse.co.uk/about/history

- ^ http://www.crmsociety.com/crmackintosh.aspx

- ^ http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/feb/11/charles-rennie-mackintoshs-genius-shines-in-his-first-ever-retrospective

- ^ "Liverpool Cathedral", The Times, 25 September 1902, p. 8

- ^ House for an Art Lover, Bellahouston Park, Glasgow 1996.

- ^ The Hunterian, The University of Glasgow. Mackintosh Collection, cat no: GLAHA 41142-45

- ^ Macintyre, Robert Hamilton (Spring 1992). "An Artist's Cottage and Studio". CRM Society Newsletter (Glasgow), No 58, p5-8.

- ^ Hall, Michael (26 November 1992). "The Artist's Cottage, Inverness". Country Life (London), p34-37.

- ^ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS), The Artist's Cottage, Canmore ID 82860

- ^ The Hunterian, The University of Glasgow. Mackintosh Collection, cat no: GLAHA 41860.

- ^ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS), Achnabechan, Canmore ID 114263

- ^ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical fascinating Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS), North House, Canmore ID 280055

- ^ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS), South House, Canmore ID 280056

- ^ "Margaret Macdonald". Undiscovered Scotland: The Ultimate Online Guide.

- ^ Gordan Tait (29 June 2004). "Rennie Mackintosh locked up as 'German spy'". The Scotsman. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- ^ "Port-Vendres, official site of the city and the tourist office – Official website". Port-vendres.com. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ The Mackintosh Trail, L'association Charles Rennie Mackintosh en Roussillon

- ^ "Library destroyed at Glasgow School of Art". Guardian.co.uk. Retrieved 25 May 2014.

- ^ "The Glasgow Story: Modern Times". City of Glasgow Culture and Leisure Services. Retrieved 22 June 2009.

- ^ Charles Rennie Mackintosh: Gallery Plan and Program Guide (1996). See also Filler, Martin (17 November 1996). "A Show on the Road May Take Many Forms". New York Times. Retrieved 7 June 2008.

- ^ "Banknote designs mark Homecoming". BBC News. 14 January 2008. Retrieved 20 January 2009.

- ^ "Art collection, including Mackintosh, sells for £1.3m". BBC News. 7 September 2012. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- ^ http://www.scotsman.com/lifestyle/arts/visual-arts/v-a-to-recreate-lost-charles-rennie-mackintosh-work-1-3824707

- Davidson, Fiona (1998). The Pitkin Guide: Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Great Britain: Pitkin Unichrome. ISBN 0-85372-874-7.

- Fiell, Charlotte and Peter (1995). Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Taschen. ISBN 3-8228-3204-9.

Further reading

- David Stark Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Co. 1854 to 2004 (2004) ISBN 1-84033-323-5

- Tamsin Pickeral; Mackintosh Flame Tree Publishing London 2005 ISBN 1-84451-258-4

- Alan Crawford Charles Rennie Mackintosh (Thames & Hudson)

- John McKean Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Architect, artist, Icon (Lomond, 2000 second edition 2001) ISBN 0-947782-08-7

- David Brett Charles Rennie Mackintosh: The Poetics of Workmanship (1992)

- Timothy Neat Part Seen Part Imagined (1994)

- John McKean Charles Rennie Mackintosh Pocket Guide (Colin Baxter, 1998 and updated editions to 2010)

- ed. Wendy Kaplan Charles Rennie Mackintosh (Abbeville Press 1996)

- John McKean, "Glasgow: from 'Universal' to 'Regionalist' City and beyond – from Thomson to Mackintosh", in Sources of Regionalism in 19th Century Architecture, Art and Literature, ed. van Santvoort, Verschaffel and De Meyer, (Leuven, 2008)

- "Fanny Blake" Essential Charles Rennie Macintosh

External links

- Mackintosh, Charles Rennie (1868–1928), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press

- Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society, Glasgow

- Unbuilt Mackintosh Models and Designs

- Charles Rennie Mackintosh – Glasgow Buildings

- The Hunterian Museum & Art Gallery: The Mackintosh House

- The Hunterian Museum & Art Gallery: The Mackintosh Collection

- paintings by Charles Rennie Mackintosh at the WikiGallery.org

- The Northern Italian Sketchbook

- National Library of Scotland: Scottish Screen Archive (Archive film "Charles Rennie Mackintosh", 1965, by the Scottish Educational Film Association)

- Charles Rennie Mackintosh buildings

- 1868 births

- 1928 deaths

- People from Townhead

- People of the Victorian era

- People of the Edwardian era

- Art Nouveau architects

- Art Nouveau designers

- Art Nouveau painters

- Arts and Crafts Movement artists

- Scottish architects

- 19th-century Scottish painters

- 20th-century Scottish painters

- Alumni of the Glasgow School of Art

- People educated at Allan Glen's School

- Scottish watercolourists

- Glasgow School

- Scottish furniture designers

- Golders Green Crematorium

- Architects from Glasgow