Cognitive distortion

A cognitive distortion is an exaggerated or irrational thought pattern involved in the onset and perpetuation of psychopathological states, especially those more influenced by psychosocial factors, such as depression and anxiety.[1] Psychiatrist Aaron T. Beck laid the groundwork for the study of these distortions, and his student David D. Burns continued research on the topic. Burns, in The Feeling Good Handbook[2] (1989), described personal and professional anecdotes related to cognitive distortions and their elimination.

Cognitive distortions are thoughts that cause individuals to perceive reality inaccurately. According to the cognitive model of Beck, a negative outlook on reality, sometimes called negative schemas (or schemata), is a factor in symptoms of emotional dysfunction and poorer subjective well-being. Specifically, negative thinking patterns reinforce negative emotions and thoughts.[3] During difficult circumstances, these distorted thoughts can contribute to an overall negative outlook on the world and a depressive or anxious mental state.

Challenging and changing cognitive distortions is a key element of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

History

In 1972, psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, and cognitive therapy scholar Aaron T. Beck published Depression: Causes and Treatment.[4] He was dissatisfied with the conventional Freudian treatment of depression, because there was no empirical evidence for the success of Freudian psychoanalysis. Beck's book provided a comprehensive and empirically supported theoretical model for depression—its potential causes, symptoms, and treatments. In Chapter 2, titled "Symptomatology of Depression", he described "cognitive manifestations" of depression, including low self-evaluation, negative expectations, self-blame and self-criticism, indecisiveness, and distortion of the body image.[4]

In 1980 Burns published Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy[5] (with a preface by Beck), and nine years later The Feeling Good Handbook, both of which built on Beck's work.

Main types

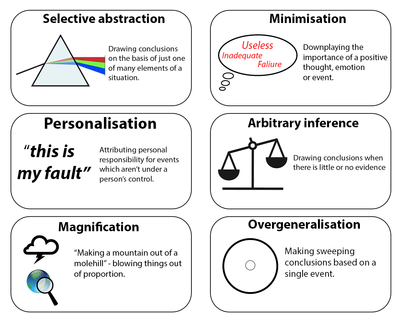

The cognitive distortions listed below[2] are categories of automatic thinking, and are to be distinguished from logical fallacies.[6]

Always being right

In this cognitive distortion, being wrong is unthinkable. This distortion is characterized by actively trying to prove one's actions or thoughts to be correct, and sometimes prioritizing self-interest over the feelings of another person.[3]

Blaming

Blaming is the opposite of personalization. In the blaming distortion, other people are held responsible for the harm they cause, and especially for their intentional or negligent infliction of emotional distress.[3]

Disqualifying the positive

Discounting positive events, such as scoring highly on an exam but not achieving a perfect score.

Emotional reasoning

In the emotional reasoning distortion, we assume that feelings expose the true nature of things and experience reality as a reflection of emotionally linked thoughts; we think something is true solely based on a feeling.

- Examples: "I feel stupid, therefore I must be stupid".[3] Feeling fear of flying in planes, and then concluding that planes must be a dangerous way to travel. Feeling overwhelmed by the prospect of cleaning one's house, therefore concluding that it's hopeless to even start cleaning.[7]

Fallacy of change

Relying on social control to obtain cooperative actions from another person[3]

Fallacy of fairness

The belief that life should be fair. When life is perceived to be unfair, an angry emotional state is produced which may lead to attempts to correct the situation.[3]

Jumping to conclusions

Reaching preliminary conclusions (usually negative) with little (if any) evidence. Two specific subtypes are identified:

- Mind reading: Inferring a person's possible or probable (usually negative) thoughts from his or her behavior and nonverbal communication; taking precautions against the worst suspected case without asking the person.

- Example: A student assumes that the readers of his or her paper have already made up their minds concerning its topic, and, therefore, writing the paper is a pointless exercise.[6]

- Fortune-telling: predicting outcomes (usually negative) of events

Labeling and mislabeling

A form of overgeneralization; attributing a person's actions to his or her character instead of to an attribute. Rather than assuming the behaviour to be accidental or otherwise extrinsic, one assigns a label to someone or something that is based on the inferred character of that person or thing.

Magnification and minimization

Giving proportionally greater weight to a perceived failure, weakness or threat, or lesser weight to a perceived success, strength or opportunity, so that the weight differs from that assigned by others, such as "making a mountain out of a molehill". In depressed clients, often the positive characteristics of other people are exaggerated and their negative characteristics are understated.

- Catastrophizing – Giving greater weight to the worst possible outcome, however unlikely, or experiencing a situation as unbearable or impossible when it is just uncomfortable

Overgeneralizing

Making hasty generalizations from insufficient evidence. Drawing a very broad conclusion from a single incident or a single piece of evidence. Even if something bad happens only once, it is expected to happen over and over again.[3]

- Example: A woman is lonely and often spends most of her time at home. Her friends sometimes ask her to dinner and to meet new people. She feels it is useless to even try. No one really could like her.[7]

Personalizing

Attributing personal responsibility, including the resulting praise or blame, to events over which the person has no control.

Making "must" or "should" statements

Making "must" or "should" statements was included by Albert Ellis in his rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT), an early form of CBT; he termed it "musturbation". Michael C. Graham called it "expecting the world to be different than it is".[8] It can be seen as demanding particular achievements or behaviours regardless of the realistic circumstances of the situation.

- Example: After a performance, a concert pianist believes he or she should not have made so many mistakes.[7]

- In Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy, David Burns clearly distinguished between pathological "should statements", moral imperatives, and social norms.

A related cognitive distortion, also present in Ellis' REBT, is a tendency to "awfulize"; to say a future scenario will be awful, rather than to realistically appraise the various negative and positive characteristics of that scenario.

Splitting (All-or-nothing thinking, black-or-white thinking, dichotomous reasoning)

Evaluating the self, as well as events in life in extreme terms. It is either all good or all bad, either black or white, nothing in between. Even small imperfections seem incredibly dangerous and painful. Splitting involves using terms like "always", "every" or "never" when they are false and misleading.

Cognitive restructuring

Cognitive restructuring (CR) is a popular form of therapy used to identify and reject maladaptive cognitive distortions[9] and is typically used with individuals diagnosed with depression.[10] In CR, the therapist and client first examine a stressful event or situation reported by the client. For example, a depressed male college student who experiences difficulty in dating might believe that his "worthlessness" causes women to reject him. Together, therapist and client might then create a more realistic cognition, e.g., "It is within my control to ask girls on dates. However, even though there are some things I can do to influence their decisions, whether or not they say yes is largely out of my control. Thus, I am not responsible if they decline my invitation." CR therapies are designed to eliminate "automatic thoughts" that include clients' dysfunctional or negative views. According to Beck, doing so reduces feelings of worthlessness, anxiety, and anhedonia that are symptomatic of several forms of mental illness.[11] CR is the main component of Beck's and Burns's cognitive behavioral therapy.[12]

Narcissistic defense

Those diagnosed with narcissistic personality disorder tend to view themselves as unrealistically superior and overemphasize their strengths but understate their weaknesses.[11] As such, narcissists use exaggeration and minimization to defend against psychic pain.[13][14]

Decatastrophizing

In cognitive therapy, decatastrophizing or decatastrophization is a cognitive restructuring technique that may be used to treat cognitive distortions, such as magnification and catastrophizing,[15] commonly seen in psychological disorders like anxiety[10] and psychosis.[16] Major features of these disorders are the subjective report of being overwhelmed by life circumstances and the incapability of affecting them.

The goal of CR is to help the client change his or her perceptions to render the felt experience as less significant.

Criticism

Common criticisms of the diagnosis of cognitive distortion relate to epistemology and the theoretical basis. The implicit assumption behind the diagnosis is that the therapist is infallible and that only the world view of the therapist is correct. If the perceptions of the patient differ from those of the therapist, it may not be because of intellectual malfunctions but because the patient has different experiences. Critics claim that there is no evidence that patients suffering from e.g. depression have dysfunctional cognitive abilities. Actually, some depressed subjects appear to be “sadder but wiser”.[17]

See also

References

- ^ Helmond, Petra; Overbeek, Geertjan; Brugman, Daniel; Gibbs, John C. (2015). "A Meta-Analysis on Cognitive Distortions and Externalizing Problem Behavior". Criminal Justice and Behavior. 42 (3): 245–262. doi:10.1177/0093854814552842.

- ^ a b Burns, David D. (1989). The Feeling Good Handbook: Using the New Mood Therapy in Everyday Life. New York: W. Morrow. ISBN 978-0-688-01745-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g Grohol, John (2009). "15 Common Cognitive Distortions". PsychCentral. Archived from the original on 2009-07-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b Beck, Aaron T. (1972). Depression; Causes and Treatment. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-7652-7.

- ^ Burns, David D. (1980). Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy. New York: Morrow. ISBN 978-0-688-03633-1.

- ^ a b Tagg, John (1996). "Cognitive Distortions". Archived from the original on November 1, 2011.

- ^ a b c Schimelpfening, Nancy. "You Are What You Think".

- ^ Graham, Michael C. (2014). Facts of Life: ten issues of contentment. Outskirts Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-4787-2259-5.

- ^ Gil, Pedro J. Moreno; Carrillo, Francisco Xavier Méndez; Meca, Julio Sánchez (2001). "Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioural treatment in social phobia: A meta-analytic review". Psychology in Spain. 5: 17–25.

- ^ a b Martin, Ryan C.; Dahlen, Eric R. (2005). "Cognitive emotion regulation in the prediction of depression, anxiety, stress, and anger". Personality and Individual Differences. 39 (7): 1249–1260. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.06.004.

- ^ a b Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association., American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 Task Force. (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. 2013. ISBN 9780890425541. OCLC 830807378.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Rush, A.; Khatami, M.; Beck, A. (1975). "Cognitive and Behavior Therapy in Chronic Depression". Behavior Therapy. 6 (3): 398–404. doi:10.1016/S0005-7894(75)80116-X.

- ^ Millon, Theodore; Carrie M. Millon; Seth Grossman; Sarah Meagher; Rowena Ramnath (2004). Personality Disorders in Modern Life. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-23734-1.

- ^ Thomas, David (2010). Narcissism: Behind the Mask. ISBN 978-1-84624-506-0.

- ^ Theunissen, Maurice; Peters, Madelon L.; Bruce, Julie; Gramke, Hans-Fritz; Marcus, Marco A. (2012). "Preoperative Anxiety and Catastrophizing". The Clinical Journal of Pain. 28 (9): 819–841. doi:10.1097/ajp.0b013e31824549d6. PMID 22760489.

- ^ Moritz, Steffen; Schilling, Lisa; Wingenfeld, Katja; Köther, Ulf; Wittekind, Charlotte; Terfehr, Kirsten; Spitzer, Carsten (2011). "Persecutory delusions and catastrophic worry in psychosis: Developing the understanding of delusion distress and persistence". Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 42 (September 2011): 349–354. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.02.003. PMID 21411041.

- ^ Beidel, Deborah C. (1986). "A Critique of the Theoretical Bases of Cognitive Behavioral Theories and Therapy". Clinical Psychology Review. 6 (2): 177–97. doi:10.1016/0272-7358(86)90011-5.