Columbia Amusement Company

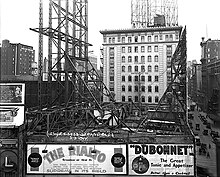

Columbia Amusement Co. Building, Manhattan, in 1917 | |

| Formation | 12 July 1902 |

|---|---|

| Legal status | Corporation |

| Purpose | Burlesque booking |

Region | United States and Canada |

Official language | English |

| Leader | Samuel A. Scribner |

| Subsidiaries | American Burlesque Association |

The Columbia Amusement Company, also called the Columbia Wheel or the Eastern Burlesque Wheel, was an industry organization that arranged burlesque company bookings in American theaters between 1902 and 1927. The burlesque companies would travel in succession round a "wheel" of theaters, ensuring steady employment for performers and a steady supply of new shows for the participating theaters. For much of its history the Columbia Wheel advertised relatively "clean" variety shows featuring pretty girls. Eventually the wheel was forced out of business due to competition from cinemas and from the cruder stock burlesque companies.

Background

The Theatrical Syndicate was formed in 1896 by the theatrical managers or booking agents Charles Frohman, Al Hayman, A. L. Erlanger, Marc Klaw, Samuel F. Nirdlinger and Frederick Zimmerman. The syndicate soon dominated legitimate theater, deciding what would be shown and where.[1] The Vaudeville Managers Association was founded soon after, with similar goals, and the United Booking Office was founded to provide a single place where performers could seek engagements.[1]

In 1898 the burlesque producers and theater managers attempted to organize in a similar way with the Travelling Variety Managers Association (TVMA). The idea was that approved shows would progress from one theater to another in succession, round a "wheel".[1] The vaudeville and burlesque producer Gus Hill claimed credit for the concept.[2] The theaters would not have to compete for shows, and the burlesque companies would have guaranteed work. The TVMA soon split into two wheels, one in the west and the other in the east.[1]

Formation

Sixteen managers and producers incorporated the Columbia Amusement Company on 12 July 1902.[3] They had left the TVMA to set up a more stable operation. The lead was taken by Sam A. Scribner. Other principals were William S. Campbell, William S. Drew, Gus Hill, John Herbert Mack, Harry Morris, L. Lawrence Weber and A. H. Woodhill.[4] The circuit had headquarter in New York and included the larger cities east of the Missouri and north of the Ohio such as Philadelphia and Pittsburg. It included Montreal and Toronto in Canada, and Boston in the east.[5] Since the theaters were in the east, the Columbia Wheel was also called the Eastern Wheel. Another circuit was formed in the west, called the Empire Circuit or Western Wheel.[4]

Early years

The Columbia organizers at first aimed to provide affordable shows that were acceptable to women and men.[4] They advertised "clean" or "refined" burlesque.[6] They included lines of chorus girls and slightly risqué comedians, but did not go so far as to give offense.[4] The Columbia Wheel's refined burlesque shows had multi-act vaudeville-style programs that included farces, comedians, skits and variety acts. In August 1905 Will Rogers signed up with Scribner for five one-week shows in Brooklyn, New York, Buffalo, Cleveland and Pittsburg.[7]

Although the wheel system made the industry more stable, the shows became standardized. New costumes and acts were expensive, and when performers became better known they often left for legitimate theater.[8] Performers who started in burlesque included Weber & Fields, Bert Lahr, W. C. Fields, Red Skelton, Sophie Tucker and Fanny Brice. All of them moved into musical comedy or vaudeville as soon as they could.[9] But the audiences still came to see the girls, and burlesque remained profitable.[8]

The Star and Garter opened in Chicago in 1908, providing "Clean Entertainment for Self-Respecting People".[9] On 10 January 1910 the Columbia Amusement Company opened the Columbia Theatre, "Home of Burlesque De Luxe", at Broadway and 47th Street in Manhattan. The theater was designed by William H. McElfatrick and had a capacity of 1,385. The company owned and operated it.[10] The Columbia theater opening was well publicized and was attended by various dignitaries.[9]

Evolution

The Empire pushed the legal limits with its "hot" shows. The Columbia often lowered its standards and competed directly with the Empire.[6] In 1913 the Eastern and Western wheels were consolidated into the Columbia Amusement Company, headed by Samuel Scribner and Isidore Herk. The combined operation put on fairly clean shows, as had the Eastern Wheel.[12] The Columbia Wheel now had two large burlesque circuits.[13] Another wheel started to compete with raunchier performances.[12] In May 1915 the company transferred its No. 2 circuit, which had forty theaters and thirty-four touring companies, to a new subsidiary corporation called the American Burlesque Association. Gus Hill was named president of the new entity.[13] The American Wheel offered rawer performances, with blue humor and suggestive dancing, and drove the competition out of business.[12]

In 1921 Scribner insisted that shows in the Columbia circuit include their own orchestras so they resembled the more respectable vaudeville shows, and banned smoking in the theaters. He also tried to ban the comedians from using double entendres, but with less success.[14] A 1922 report said "the companies will come to town on the same day each week to offer what is declared to be comedies with music, musical shows with chorus girls or whatever may best describe clean, wholesome offerings that should not be confused with "burlesque" as it was presented when Dad was a young chap."[5]

The Columbia Wheel avoided runways until its final years, although the subsidiary American Wheel offered cooch dancers performing on runways.[15] In 1922 the American Wheel was dissolved due to an argument between Scribner and Herk and replaced by the Mutual Wheel.[12] Herk headed up the Mutual.[14] Performers for the Mutual Wheel became the first to expose their breasts. The Mutual put on less elaborate shows with more tease, although it generally did not include stripping.[16] The Mutual grew fast, buying up Columbia theaters across the country.[17]

Decline and dissolution

In 1923 Columbia still had thirty-eight shows, and was still the largest burlesque operation in the country. However, receipts were declining.[12] By the mid-1920s cinemas were providing shows that combined film and live entertainment with ticket prices lower than any burlesque show.[18] In the 1925 season Scribner authorized the removal of tights, and tableaux of bare-breasted women. Columbia continued to lose customers to other types of entertainment and to more explicit stock burlesque theaters.[12]

Columbia and Mutual merged in 1927 to form the United Burlesque Association.[16] Herk, President of the Mutual Wheel, became President of the new combination, with Scribner, formerly president of the Columbia Wheel, as the Chairman of the Board.[19] The new organization comprised 44 theaters,[19] and soon reverted to the name Mutual Burlesque Circuit.[20][21]

By the 1927–28 season the combined circuit was struggling financially. This was the last season where cartoon theatricals were a significant part of the burlesque shows.[22] In 1930–31 the combined wheel decided to revive clean burlesque. The experiment failed and the circuit closed.[12]

References

Citations

- ^ a b c d Cullen, Hackman & McNeilly 2004, p. 252.

- ^ Cullen, Hackman & McNeilly 2004, p. 510.

- ^ Winchester 1995, p. 16.

- ^ a b c d Cullen, Hackman & McNeilly 2004, p. 253.

- ^ a b Columbia Wheel Shows, Reading Eagle 1922.

- ^ a b Allen 1991, p. 191-192.

- ^ Dodge & Rogers 2000, p. 183.

- ^ a b Briggeman 2004, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Wagenknecht 1982, p. 268.

- ^ Columbia Theatre, MCNY.

- ^ Winchester 1995, p. 29.

- ^ a b c d e f g Allen 1991, p. 249.

- ^ a b New Burlesque Circuit, NYT 1915.

- ^ a b Shteir 2004, p. 72.

- ^ Briggeman 2004, p. 14.

- ^ a b Briggeman 2004, p. 15.

- ^ Shteir 2004, p. 73.

- ^ Allen 1991, p. 244.

- ^ a b Buffalo Currier Express, January 15, 1928

- ^ Brooklyn Standard Union August 2, 1929, pg. 8

- ^ Philadelphia Inquirer May 19, 1929, pg 12

- ^ Winchester 1995, p. 30.

Sources

- Allen, Robert Clyde (1991). Horrible Prettiness: Burlesque and American Culture. Univ of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4316-1. Retrieved 2014-05-14.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Briggeman, Jane (2004-09-01). Burlesque: Legendary Stars of the Stage. Collectors Press, Inc. ISBN 978-1-888054-94-1. Retrieved 2014-05-14.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Columbia Theatre". Museum of the City of New York. Retrieved 2014-05-14.

- "Columbia Wheel Shows". Reading Eagle. 2 October 1922. Retrieved 2014-05-14.

- Cullen, Frank; Hackman, Florence; McNeilly, Donald (2004). "Gus Hill". Vaudeville old & new: an encyclopedia of variety performances in America. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-93853-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dodge, Richard Irving; Rogers, Will (2000). The Indian Territory Journals of Colonel Richard Irving Dodge. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3267-9. Retrieved 2014-05-14.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "New Burlesque Circuit". New York Times Article. 10 May 1915.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Shteir, Rachel (2004-11-01). Striptease : The Untold History of the Girlie Show: The Untold History of the Girlie Show. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-802935-9. Retrieved 2014-05-14.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wagenknecht, Edward (1982). American Profile, 1900–1909. Univ of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 0-87023-351-3. Retrieved 2014-05-14.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Winchester, Mark David (1995). "Cartoon Theatricals from 1896 to 1927: Gus Hill's Cartoon Shows for the American Road Theatre". Ohio State University. Retrieved 2014-05-13.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)