Convex curve

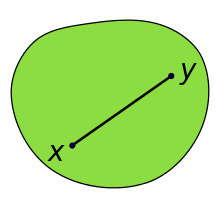

In geometry, a convex curve is a curve in the Euclidean plane which lies completely on one side of each and every one of its tangent lines.

The boundary of a convex set is always a convex curve.

Definitions

Definition by supporting lines

Any straight line L divides the Euclidean plane to two half-planes whose union is the entire plane and whose intersection is L . We say that a curve C "lies on one side of L" if it is entirely contained in one of the half-planes. A plane curve is called convex if it lies on one side of each of its tangent lines.[1] In other words, a convex curve is a curve that has a supporting line through each of its points.

Definition by convex sets

A convex curve may be defined as the boundary of a convex set in the Euclidean plane. This definition is more restrictive than the definition in terms of tangent lines; in particular, with this definition, a convex curve can have no endpoints.[2]

Sometimes, a looser definition is used, in which a convex curve is a curve that forms a subset of the boundary of a convex set. For this variation, a convex curve may have endpoints.

Strictly convex curve

A strictly convex curve is a convex curve that does not contain any line segments. Equivalently, a strictly convex curve is a curve that intersects any line in at most two points,[3][4] or a simple curve in convex position, meaning that none of its points is a convex combination of any other subset of its points.

Properties

Every convex curve that is the boundary of a closed convex set has a well-defined finite length. That is, these curves are a subset of the rectifiable curves.[2]

According to the four-vertex theorem, every smooth convex curve that is the boundary of a closed convex set has at least four vertices, points that are local minima or local maxima of curvature.[4][5]

Parallel tangents

A curve C is convex if and only if there are no three different points in C such that the tangents in these points are parallel.

Proof:

⇒ If there are three parallel tangents, then one of them, say L, must be between the other two. This means that C lies on both sides of L, so it cannot be convex.

⇐ If C is not convex, then by definition there is point p on C such that the tangent line at p (call it L) has C on both sides of it. Since C is closed, if we trace the part of C that lies on one side of L we eventually get at a point q1 which is farthest from L.[1] The tangent to C at q1 (call it L1) must be parallel to L. The same is true in the other side of L - there is a point q2 and a tangent L2 which is parallel to L. Thus there are three different points, {p,q1,q2}, such that their tangents are parallel.

Monotonicity of turning angle

A curve is called simple if it does not intersect itself. A closed regular plane simple curve C is convex if and only if its curvature is either always non-negative or always non-positive—i.e., if and only if the turning angle (the angle of the tangent to the curve) is a weakly monotone function of the parametrization of the curve.[6]

Proof:

⇐ If C is not convex, then by the parallel tangents lemma there are three points {p,q1,q2} such that the tangents at these points are parallel. At least two must have their signed tangents pointing in the same direction. Without loss of generality, assume that these points are q1 and q2. This means that the difference in the turning angle when going from q1 to q2 is a multiple of 2π. There are two possibilities:

- The difference in turning angle from q1 to q2 is 0. Then, if the turning angle would be a monotone function, it should be constant between q1 and q2, so that the curve between these two lines should be a straight line. But this would mean that the two tangent lines L1 and L2 are the same line—a contradiction.

- The difference in turning angle from q1 to q2 is a non-zero multiple of 2π. Because the curve is simple (does not intersect itself), the entire change in the turning angle around the curve must be exactly 2π.[7] This means that the difference in the turning angle from q2 to q1 must be 0, so by the same reasoning as before we get at a contradiction.

Thus we have proved that if C is not convex, the turning angle cannot be a monotone function.

⇒ Assume that the turning angle is not monotone. Then we can find three points on the curve, s1<s0<s2, such that the turning angle at s1 and s2 is the same and different than the turning angle at s0. In a simple closed curve, all turning angles are covered. In particular, there is a point s3 in which the turning angle is minus the turning angle at s1. Now we have three points, {s1,s2,s3}, whose turning angle differs in a multiple of π. There are two possibilities:

- If the tangents at these three points are all distinct, then they are parallel, and by the parallel tangents lemma, C is not convex.

- Otherwise, there are two distinct points of C, say p and q, that lie on the same tangent line, L. There are two sub-cases:

- If L is not contained in C, then consider the line perpendicular to L at a certain point, r, which is not a point of C. This perpendicular line intersects C at two points, say r1 and r2. The tangent to C at r1 has at least one of the points {p,q,r2} on each side, so C is not convex.

- If L is contained in C, then the two points p and q have the same turning angle and so they must be s1 and s2. But this contradicts the assumption that there is a point s0 between s1 and s2 with a different turning angle.

Thus we have proved that if the turning angle is not monotone, the curve cannot be convex.

Related shapes

Smooth convex curves with an axis of symmetry may sometimes be called ovals.[8] However, in finite projective geometry, ovals are instead defined as sets for which each point has a unique line disjoint from the rest of the set, a property that in Euclidean geometry is true of the smooth strictly convex closed curves.

See also

References

- ^ a b Gray, Alfred (1998). Modern differential geometry of curves and surfaces with Mathematica. Boca Raton: CRC Press. p. 163. ISBN 0849371643.

- ^ a b Toponogov, Victor Andreevich (2006), Differential Geometry of Curves and Surfaces: A Concise Guide, Springer, p. 15, ISBN 9780817643843.

- ^ Girko, Vyacheslav L. (1975), Spectral Theory of Random Matrices, Academic Press, p. 352, ISBN 9780080873213.

- ^ a b Bär, Christian (2010), Elementary Differential Geometry, Cambridge University Press, p. 49, ISBN 9780521896719.

- ^ DeTruck, D.; Gluck, H.; Pomerleano, D.; Vick, D.S. (2007), "The four vertex theorem and its converse" (PDF), Notices of the American Mathematical Society, 54 (2): 9268, arXiv:math/0609268, Bibcode:2006math......9268D.

- ^ Gray, Alfred (1998). Modern differential geometry of curves and surfaces with Mathematica. Boca Raton: CRC Press. pp. 163–165. ISBN 0849371643.

- ^ This is by a theorem by Heinz Hopf: the turning number of a simple closed plane curve is either +1 or -1.

- ^ Schwartzman, Steven (1994), The Words of Mathematics: An Etymological Dictionary of Mathematical Terms Used in English, MAA Spectrum, Mathematical Association of America, p. 156, ISBN 9780883855119.