Corps expéditionnaire d'Orient

| Corps Expeditionnaire d'Orient | |

|---|---|

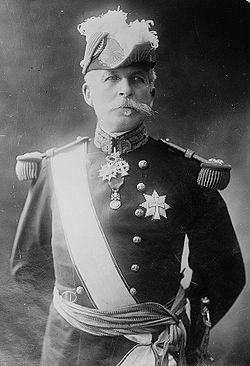

Albert d'Amade, the CEO's first commander | |

| Active | 1915–1916 |

| Country | |

| Role | Expeditionary force |

| Size | 1–2 divisions |

| Engagements | World War I |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Albert d'Amade Henri Gouraud Maurice Bailloud |

The Corps Expeditionnaire d'Orient (Oriental Expeditionary Force) (CEO) was a French Expeditionary Force raised for service during the Gallipoli Campaign in World War I. The corps initially consisted of a single infantry division that was raised in North Africa from metropolitan French and French colonial African soldiers, but later grew to two divisions. It took part in fighting around Kum Kale, on the Asiatic side of the Dardanelles, at the start of the campaign before being moved to Cape Helles where it fought alongside British formations for the remainder of the campaign. In October 1915, the corps was reduced to one division again and was finally evacuated from the Gallipoli Peninsula in January 1916 when it ceased to exist.

Formation

Initially, the force consisted of 16,700 troops organised into one division, made up of two brigades, which had been raised from the 17th Colonial Division in North Africa and included both "metropolitan" French and colonial African troops.[1][2][3] The so-called metropolitan units included four battalions of zouaves mainly recruited from French settlers in Algeria and Tunisia, the 175th regiment of French line infantry and one battalion of the Foreign Legion. The colonial troops consisted of battalions of both West African Tirailleurs Senegalais and white regulars of colonial infantry, initially organised into the 6th regiment de march colonial d'infanterie.[4] The force had a strong divisional artillery, consisting of six field and two mountain batteries,[5] but having been raised quickly, it received only limited training as a formation, and with only two brigades it was smaller than the British divisions that took part in the campaign.[1] Later in the campaign, the corps was expanded to include a second division, raised from the 156th Infantry Division.[6] At its height, the corps' strength was around 42,000 men.[7]

Operational service

Following the Ottoman Empire's entry into the war on the Central Powers side in late 1914, the Allies began preparations to capture the Dardanelles in order to secure a supply route to Russia.[8] As part of these preparations, the Corps Expeditionnaire d'Orient was raised on 22 February 1915[9] under the command of General Albert d'Amade, who had previously served in Morocco and the Western Front.[10]

Throughout February and March, Anglo-French naval forces attempted to penetrate the Dardanelles, aided by small landing parties that were put ashore to destroy Ottoman fortifications.[11] Several small-scale operations were undertaken, starting on 19 February, but they were hampered by bad weather which delayed the main attack until 18 March. Entering the straits in broad daylight, the force was heavily engaged by Ottoman shore batteries and following heavy losses from mines and shelling, they were forced to turn back.[12] After this, the Allied strategy to capture the Dardanelles turned towards a large-scale landing.[13]

Hastily formed, after assembling on Lemnos there had been no time for the corps to undertake large-scale training before it was committed to the land campaign.[1] During the initial Allied landing on 25 April, the corps undertook a diversionary landing on the Dardanelles Asiatic coast around Kum Kale, to divert Ottoman forces away from the main landings on the Gallipoli Peninsula,[14] and to disrupt Ottoman artillery that could have fired upon the main landings. The 6th Colonial Regiment led the division ashore, supported by three battleships and a Russian warship. Part of the first wave was turned back by heavy fire, but the rest managed to get ashore and they proceeded to secure the village and an Ottoman fort. Throughout the course of 26 April, the Ottoman 3rd Division counterattacked, but the following day, having lost over 2,200 killed or wounded, the Ottomans began surrendering to the French in large numbers. Nevertheless, they were withdrawn shortly afterwards, having lost about 300 killed and 500 wounded.[15][16]

Following this, the French force re-embarked and was landed at Cape Helles, where they took up a position on the right flank around 'S' Beach.[17] With a strength of 24 battalions,[7] they subsequently took part in the First Battle of Krithia on 28 April.[18] In early May, the Ottoman forces launched a heavy counterattack on the Allied positions with a force of over 16,000 men. The attack was beaten back, but the French division suffered heavy casualties – up to 2,000 men – and at the height of the assault some of the Senegalese and Zouaves "broke and ran".[19] As a result, the 2nd Naval Brigade from the British Royal Naval Division, had to take over some of their positions.[20] Reinforcements were brought in, including a second French division, which arrived between 6 and 8 May, although they did not arrive in time to take part in the Second Battle of Krithia, during which the 1st Division attacked towards the Kereves Dere gully, and although they made slow progress they eventually managed to secure the high ground overlooking this position before the attack petered out.[6][21]

D'Amade was replaced as commander of the corps in late May when he was dismissed and recalled to France. He was replaced by General Henri Gouraud.[22] On 4 June, both divisions took part in the Third Battle of Krithia, once again forming the right of the Allied line as part of the effort to take Achi Baba, a high feature that dominated the Allied position.[23] The six French batteries were detached to support the British,[24] while the infantry were tasked with attacking the Haricot Redoubt, overlooking the Kereves Dere spur.[23] Attacking in daylight, but possessing a numerical superiority, the Allies made ground across a broad front, before the French were forced back by an Ottoman counterattack. Regaining positions on the right, the Ottomans were able to enfilade the British positions and eventually they too were forced back, and the attack ultimately failed.[25] In preparation for the August Offensive, minor attacks continued around Helles, and the French undertook further attacks on the Haricot Redoubt, which they subsequently took on 21 June albeit with heavy casualties.[26]

On 30 June, command of the corps changed again when Gouraud, who had been viewed with considerable respect by the British commander, Ian Hamilton, was wounded while touring the front line to boost the morale of his troops. He was replaced by Maurice Bailloud, who had previously commanded one of the corps' divisions.[27]

A period of stalemate followed, and after the August Offensive failed to break the deadlock, the Allied commanders at Gallipoli requested heavy reinforcements. The French initially proposed to send a further four divisions, but following Bulgaria's entry into the war, this was cancelled, and in late September one of the corps' divisions was diverted to Salonika, on the Macedonian front.[28][29] As the French began to refocus their actions in the Mediterranean around Salonika, in early October, the Corps Expeditionnaire d'Orient was renamed the "Corps Expeditionnaire des Dardanelles";[30] nevertheless, a total of 21,000 French troops remained on the peninsula to show political support to the British.[19] The corps remained in existence until 6 January 1916 when, following the evacuation of French forces from the peninsula, it was subsumed into the larger Army of the Orient serving in Salonika.[9] Around 80,000 men served in the two French divisions. Casualties during the campaign amounted to around 47,000 killed, wounded or sick.[31]

Order of battle

Source:[5]

1st Division (17th Colonial Division) under Jean-Marie Brulard

- 1 Metropolitan Brigade

- 175th Regiment

- Composite Regiment of Zouaves and Foreign Legion

- Colonial Brigade

- 4th Colonial Regiment

- 6th Colonial Regiment

- Six field artillery batteries (operating Soixante-Quinze 75mm field guns)

- Two mountain batteries

2nd Division (156th Infantry Division) under Maurice Bailloud

- 2 Metropolitan Brigade

- 176th Regiment

- 2nd African Regiment (Zouaves)

- Colonial Brigade

- 7th Colonial Regiment

- 8th Colonial Regiment

- Six field artillery batteries (Soixante-Quinze 75mm field guns)

- Two mountain batteries

Notes

- ^ a b c Erickson 2001, p. 1004.

- ^ Haythornthwaite 2004, p. 39.

- ^ Organisation CEO 22 February 1915.

- ^ Hure 1972, p. 302.

- ^ a b Haythornthwaite 2004, p. 25.

- ^ a b Haythornthwaite 2004, pp. 55–56.

- ^ a b Hughes 2005, p. 64.

- ^ Haythornthwaite 2004, p. 6.

- ^ a b Moore & Drecki 2013, p. 34.

- ^ Haythornthwaite 2004, p. 14.

- ^ Haythornthwaite 2004, p. 27.

- ^ Haythornthwaite 2004, pp. 28–33.

- ^ Haythornthwaite 2004, p. 33.

- ^ Broadbent 2005, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Broadbent 2005, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Haythornthwaite 2004, pp. 45–49.

- ^ Broadbent 2005, p. 123.

- ^ Broadbent 2005, p. 125.

- ^ a b Hughes 2005, p. 66.

- ^ Haythornthwaite 2004, p. 55.

- ^ Broadbent 2005, p. 138.

- ^ Haythornthwaite 2004, pp. 15 & 61.

- ^ a b Broadbent 2005, p. 171.

- ^ Haythornthwaite 2004, p. 61.

- ^ Haythornthwaite 2004, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Broadbent 2005, p. 186.

- ^ Haythornthwaite 2004, p. 15.

- ^ Baldwin 1962, pp. 61 and 66.

- ^ Aspinall-Oglander 1992, pp. 363–376.

- ^ Dutton 1998, p. 155.

- ^ Erickson 2001, p. 1009.

References

- Aspinall-Oglander, C. F. (1992) [1932]. Military Operations Gallipoli, Vol II: May 1915 to the Evacuation. London: IWM & Battery Press. ISBN 0-89839-175-X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Baldwin, Hanson (1962). World War I: An Outline History. London: Hutchinson. OCLC 793915761.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Broadbent, Harvey (2005). Gallipoli: The Fatal Shore. Camberwell, Victoria: Viking/Penguin. ISBN 0-670-04085-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Corps expéditionnaire d'Orient (C.E.O.): J.M.O. 22 février-5 mai 1915: 26 N 75/1". Mémoire des hommes: Journaux des Unites (1914-1918) (in French). Ministere De la Defense. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- Dutton, David (1998). The Politics of Diplomacy: Britain, France and the Balkans in the First World War. London: I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9781860641121.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Erickson, Edward (2001). "Strength Against Weakness: Ottoman Military Effectiveness at Gallipoli, 1915". The Journal of Military History. 65: 981–1012. doi:10.2307/2677626. ISSN 1543-7795.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Haythornthwaite, Philip (2004) [1991]. Gallipoli 1915: Frontal Assault on Turkey. Campaign Series #8. London: Osprey. ISBN 0-275-98288-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hughes, Matthew (2005). "The French Army at Gallipoli". The RUSI Journal. 153 (3): 64–67. ISSN 0307-1847.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hure, R. (1972). L'Armee d'Afrique 1830–1962. Paris: Charles-Lavauzelle. OCLC 464095274.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Moore, Antoni; Drecki, Igor (2013). Geospatial Visualisation. New York: Springer. ISBN 9783642122897.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)