Crossing number (graph theory)

In graph theory, the crossing number cr(G) of a graph G is the lowest number of edge crossings of a plane drawing of the graph G. For instance, a graph is planar if and only if its crossing number is zero.

The mathematical origin of the study of crossing numbers is in Turán's brick factory problem, in which Pál Turán asked to determine the crossing number of the complete bipartite graph Km,n.[1] However, the same problem of minimizing crossings was also considered in sociology at approximately the same time as Turán, in connection with the construction of sociograms.[2] It continues to be of great importance in graph drawing.

Without further qualification, the crossing number allows drawings in which the edges may be represented by arbitrary curves; the rectilinear crossing number requires all edges to be straight line segments, and may differ from the crossing number. In particular, the rectilinear crossing number of a complete graph is essentially the same as the minimum number of convex quadrilaterals determined by a set of n points in general position, closely related to the Happy Ending problem.[3]

History

During World War II, Hungarian mathematician Pál Turán was forced to work in a brick factory, pushing wagon loads of bricks from kilns to storage sites. The factory had tracks from each kiln to each storage site, and the wagons were harder to push at the points where tracks crossed each other, from which Turán was led to ask his brick factory problem: what is the minimum possible number of crossings in a drawing of a complete bipartite graph?[4]

Zarankiewicz attempted to solve Turán's brick factory problem;[5] his proof contained an error, but he established a valid upper bound of

for the crossing number of the complete bipartite graph Km,n. The conjecture that this inequality is actually an equality is now known as Zarankiewicz' crossing number conjecture. The gap in the proof of the lower bound was not discovered until eleven years after publication, nearly simultaneously by Gerhard Ringel and Paul Kainen; see [6]

The problem of determining the crossing number of the complete graph was first posed by Anthony Hill, and appears in print in 1960.[7] Hill and his collaborator John Ernest were two constructionist artists fascinated by mathematics, who not only formulated this problem but also originated a conjectural upper bound for this crossing number, which Richard K. Guy published in 1960.,[7] namely

which gives values of for see sequence (A000241) in the OEIS. An independent formulation of the conjecture was made by Thomas L. Saaty in 1964.[8] Saaty further verified that the upper bound is achieved for and Pan and Richter showed that it also is achieved for If only straight-line segments are permitted, then one needs more crossings. The rectilinear crossing numbers for K5 through K12 are 1, 3, 9, 19, 36, 62, 102, 153, (A014540) and values up to K27 are known, with K28 requiring either 7233 or 7234 crossings. Further values are collected by the Rectilinear Crossing Number project.[9] Interestingly, it is not known whether the ordinary and rectilinear crossing numbers are the same for bipartite complete graphs. If the Zarankiewicz conjecture is correct, then the formula for the crossing number of the complete graph is asymptotically correct;[10] that is,

As of January 2012, crossing numbers are known for very few graph families. In particular, except for a few initial cases, the crossing number of complete graphs, bipartite complete graphs, and products of cycles all remain unknown. There has been some progress on lower bounds, as reported by de Klerk et al. (2006).[11]

The Albertson conjecture, formulated by Michael O. Albertson in 2007, states that, among all graphs with chromatic number n, the complete graph Kn has the minimum number of crossings. That is, if the Guy-Saaty conjecture on the crossing number of the complete graph is valid, every n-chromatic graph has crossing number at least equal to the formula in the conjecture. It is now known to hold for n ≤ 16.[12]

Complexity

In general, determining the crossing number of a graph is hard; Garey and Johnson showed in 1983 that it is an NP-hard problem.[13] In fact the problem remains NP-hard even when restricted to cubic graphs[14] and to near-planar graphs[15] (graphs that become planar after removal of a single edge). More specifically, determining the rectilinear crossing number is complete for the existential theory of the reals.[16]

On the positive side, there are efficient algorithms for determining if the crossing number is less than a fixed constant k — in other words, the problem is fixed-parameter tractable.[17] It remains difficult for larger k, such as |V|/2. There are also efficient approximation algorithms for approximating cr(G) on graphs of bounded degree.[18] In practice heuristic algorithms are used, such as the simple algorithm which starts with no edges and continually adds each new edge in a way that produces the fewest additional crossings possible. These algorithms are used in the Rectilinear Crossing Number[19] distributed computing project.

Crossing numbers of cubic graphs

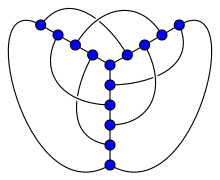

The smallest cubic graphs with crossing numbers 1–8 are known (sequence A110507 in the OEIS). The smallest 1-crossing cubic graph is the complete bipartite graph K3,3, with 6 vertices. The smallest 2-crossing cubic graph is the Petersen graph, with 10 vertices. The smallest 3-crossing cubic graph is the Heawood graph, with 14 vertices. The smallest 4-crossing cubic graph is the Möbius-Kantor graph, with 16 vertices. The smallest 5-crossing cubic graph is the Pappus graph, with 18 vertices. The smallest 6-crossing cubic graph is the Desargues graph, with 20 vertices. None of the four 7-crossing cubic graphs, with 22 vertices, are well known.[20] The smallest 8-crossing cubic graphs include the Nauru graph and the McGee graph or (3,7)-cage graph, with 24 vertices.

In 2009, Exoo conjectured that the smallest cubic graph with crossing number 11 is the Coxeter graph, the smallest cubic graph with crossing number 13 is the Tutte–Coxeter graph and the smallest cubic graph with crossing number 170 is the Tutte 12-cage.[21][22]

The crossing number inequality

The very useful crossing number inequality, discovered independently by Ajtai, Chvátal, Newborn, and Szemerédi[23] and by Leighton,[24] asserts that if a graph G (undirected, with no loops or multiple edges) with n vertices and e edges satisfies

then we have

The constant 29 is the best known to date, and is due to Ackerman;[25] the constant 7.5 can be lowered to 4, but at the expense of replacing 29 with the worse constant of 64.

The motivation of Leighton in studying crossing numbers was for applications to VLSI design in theoretical computer science. Later, Székely[26] also realized that this inequality yielded very simple proofs of some important theorems in incidence geometry, such as Beck's theorem and the Szemerédi-Trotter theorem, and Tamal Dey used it to prove upper bounds on geometric k-sets.[27]

For graphs with girth larger than 2r and e ≥ 4n, Pach, Spencer and Tóth[28] demonstrated an improvement of this inequality to

Proof of crossing number inequality

We first give a preliminary estimate: for any graph G with n vertices and e edges, we have

To prove this, consider a diagram of G which has exactly cr(G) crossings. Each of these crossings can be removed by removing an edge from G. Thus we can find a graph with at least edges and n vertices with no crossings, and is thus a planar graph. But from Euler's formula we must then have , and the claim follows. (In fact we have for n ≥ 3).

To obtain the actual crossing number inequality, we now use a probabilistic argument. We let 0 < p < 1 be a probability parameter to be chosen later, and construct a random subgraph H of G by allowing each vertex of G to lie in H independently with probability p, and allowing an edge of G to lie in H if and only if its two vertices were chosen to lie in H. Let denote the number of edges of H, and let denote the number of vertices.

Now consider a diagram of G with cr(G) crossings. We may assume that any two edges in this diagram with a common vertex are disjoint, otherwise we could interchange the intersecting parts of the two edges and reduce the crossing number by one. Thus every crossing in this diagram involves four distinct vertices of G.

Since H is a subgraph of G, this diagram contains a diagram of H; let denote the number of crossings of this random graph. By the preliminary crossing number inequality, we have

Taking expectations we obtain

Since each of the n vertices in G had a probability p of being in H, we have . Similarly, since each of the edges in G has a probability of remaining in H (since both endpoints need to stay in H), then . Finally, every crossing in the diagram of G has a probability of remaining in H, since every crossing involves four vertices, and so . Thus we have

If we now set p to equal 4n/e (which is less than one, since we assume that e is greater than 4n), we obtain after some algebra

A slight refinement of this argument allows one to replace 64 by 33.75 when e is greater than 7.5 n.[25]

See also

Notes

- ^ Turán, P. (1977). "A Note of Welcome". J. Graph Theory. 1: 7–9. doi:10.1002/jgt.3190010105.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Bronfenbrenner, Urie (1944). "The graphic presentation of sociometric data". Sociometry. 7 (3): 283–289. JSTOR 2785096.

The arrangement of subjects on the diagram, while haphazard in part, is determined largely by trial and error with the aim of minimizing the number of intersecting lines.

{{cite journal}}: line feed character in|quote=at position 32 (help) - ^ Scheinerman, Edward R.; Wilf, Herbert S. (1994). "The rectilinear crossing number of a complete graph and Sylvester's "four point problem" of geometric probability". American Mathematical Monthly. 101 (10): 939–943. doi:10.2307/2975158. JSTOR 2975158.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Pach, János; Sharir, Micha (2009). "5.1 Crossings—the Brick Factory Problem". Combinatorial Geometry and Its Algorithmic Applications: The Alcalá Lectures. Mathematical Surveys and Monographs. Vol. 152. American Mathematical Society. pp. 126–127.

- ^ Zarankiewicz, K. (1954). "On a Problem of P. Turán Concerning Graphs". Fund. Math. 41: 137–145.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Guy, R.K. (1969). "Decline and fall of Zarankiewicz's Theorem". Proof Techniques in Graph Theory (Ed. by F. Harary), Academic Press: 63–69.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b Guy, R.K. (1960). "A combinatorial problem". Nabla (Bulletin of the Malayan Mathematical Society). 7: 68–72.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Saaty, T.L. (1964). "The minimum number of intersections in complete graphs". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 52: 688–690. doi:10.1073/pnas.52.3.688.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Oswin Aichholzer. "Rectilinear Crossing Number project".

- ^ Kainen, P.C. (1968). "On a problem of P. Erdos". Journal of Combinatorial Theory. 5: 374–377. doi:10.1016/s0021-9800(68)80013-4.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ de Klerk, E.; Maharry, J.; Pasechnik, D. V.; Richter, B.; Salazar, G. (2006). "Improved bounds for the crossing numbers of Km,n and Kn". SIAM Journal on Discrete Mathematics. 20 (1): 189–202. doi:10.1137/S0895480104442741Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link). - ^ Barát, János; Tóth, Géza (2009). "Towards the Albertson Conjecture". arXiv:0909.0413 [math.CO].

{{cite arXiv}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Garey, M. R.; Johnson, D. S. (1983). "Crossing number is NP-complete". SIAM J. Alg. Discr. Meth. 4 (3): 312–316. doi:10.1137/0604033. MR 0711340.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hliněný, P. (2006). "Crossing number is hard for cubic graphs". Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series B. 96 (4): 455–471. doi:10.1016/j.jctb.2005.09.009. MR 2232384.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Cabello S. and Mohar B. (2013). "Adding One Edge to Planar Graphs Makes Crossing Number and 1-Planarity Hard". SIAM Journal on Computing. 42 (5): 1803–1829. doi:10.1137/120872310.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Schaefer, Marcus (2010). "Complexity of some geometric and topological problems" (PDF). Graph Drawing, 17th International Symposium, GS 2009, Chicago, IL, USA, September 2009, Revised Papers. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 5849. Springer-Verlag. pp. 334–344. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-11805-0_32. ISBN 978-3-642-11804-3.

{{cite conference}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help). - ^ Grohe, M. (2005). "Computing crossing numbers in quadratic time". J. Comput. System Sci. 68 (2): 285–302. doi:10.1016/j.jcss.2003.07.008. MR 2059096.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Kawarabayashi, Ken-ichi; Reed, Bruce (2007). "Computing crossing number in linear time". Proceedings of the 29th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing. pp. 382–390. doi:10.1145/1250790.1250848. ISBN 978-1-59593-631-8.{{cite conference}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Even, Guy; Guha, Sudipto; Schieber, Baruch (2003). "Improved Approximations of Crossings in Graph Drawings and VLSI Layout Areas". SIAM Journal on Computing. 32 (1): 231–252. doi:10.1137/S0097539700373520.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Rectilinear Crossing Number on the Institute for Software Technology at Graz, University of Technology (2009).

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Graph Crossing Number". MathWorld.

- ^ Exoo, G. "Rectilinear Drawings of Famous Graphs".

- ^ Pegg, E. T.; Exoo, G. (2009). "Crossing Number Graphs". Mathematica Journal. 11Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link). - ^ Ajtai, M.; Chvátal, V.; Newborn, M.; Szemerédi, E. (1982). "Crossing-free subgraphs". Theory and Practice of Combinatorics. North-Holland Mathematics Studies. Vol. 60. pp. 9–12. MR 0806962.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Leighton, T. (1983). Complexity Issues in VLSI. Foundations of Computing Series. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- ^ a b Ackerman, Eyal (2013), On topological graphs with at most four crossings per edge (PDF). For earlier results with worse constants see Pach, János; Tóth, Géza (1997), "Graphs drawn with few crossings per edge", Combinatorica, 17 (3): 427–439, doi:10.1007/BF01215922, MR 1606052; Pach, János; Radoičić, Radoš; Tardos, Gábor; Tóth, Géza (2006), "Improving the crossing lemma by finding more crossings in sparse graphs", Discrete and Computational Geometry, 36 (4): 527–552, doi:10.1007/s00454-006-1264-9, MR 2267545.

- ^ Székely, L. A. (1997). "Crossing numbers and hard Erdős problems in discrete geometry". Combinatorics, Probability and Computing. 6 (3): 353–358. doi:10.1017/S0963548397002976. MR 1464571.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Dey, T. L. (1998). "Improved bounds for planar k-sets and related problems". Discrete and Computational Geometry. 19 (3): 373–382. doi:10.1007/PL00009354. MR 1608878.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Pach, János; Spencer, Joel; Tóth, Géza (2000). "New bounds on crossing numbers". Discrete and Computational Geometry. 24 (4): 623–644. doi:10.1007/s004540010011.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)