Dane axe

The Dane Axe is an early type of battle axe, primarily used during the transition between the European Viking Age and early Middle Ages. Other names for the weapon include English Long Axe, Danish Axe, and Hafted Axe.

Construction

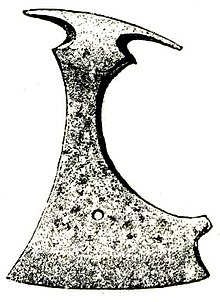

Most axes, both in period illustrations and extant artifact, that fall under the description of Danish Axe, possess Type L or Type M heads according to the Petersen axe typology.[1] Both types consist of a wide, thin blade, with pronounced "horns" at both the toe and heel of the bit. Cutting surface varies, but is generally between 20 cm and 30 cm (8 and 12 inches). Type L blades tend to be smaller, with the toe of the bit swept forward for superior shearing capability. Later Type M blades are typically larger overall, with a more symmetrical toe and heel.

The blade itself was reasonably light and forged very thin, making it superb for cutting. The fatness of the body on top the edge is as thin as 2mm. Many of these axes were constructed with a reinforced bit, typically of a higher carbon steel to facilitate a harder, sharper edge. Average weight of an axe this size is between 1 kg and 2 kg (2 and 4 pounds). Proportionally, the long axe has more in common with a modern meat cleaver than a wood axe. This complex construction results in a lively and quick weapon with devastating cutting ability.

Based on period depictions, the haft of a Longaxe for combat was usually between approx. 0.9 m and 1.2 m (3 and 4 feet) long, although Dane axes used as status symbols might be as long as 1.5 to 1.7 m (5 to 5½ ft). Such axes might also feature inlaid silver and frequently may not have the flared steel edge of a weapon designed for war. Some surviving examples also feature a brass haft cap, often richly decorated, which presumably served to keep the head of the weapon secure on the haft, as well as protecting the end of the haft from the rigors of battle. Ash and oak are the most likely materials for the haft, as they have always been the primary materials used for polearms in Europe.

History

In the course of the 10-11th centuries, the Danish Axe gained popularity in areas outside Scandinavia where Viking influence was strong, such as England, Ireland and Normandy. Historical accounts depict the Danish Axe as the weapon of the warrior elite in this period, such as the Huscarls of Anglo-Saxon England.[citation needed] In the Bayeux tapestry, a visual record of the ascent of William the Conqueror to the throne of England, the axe is almost exclusively wielded by well armoured huscarls. These huscarls formed the core bodyguard of King Harold at the Battle of Hastings. The Bayeux Tapestry also depicts a huscarl cleaving a Norman knight's horse's head with one blow.[2] The Dane-Axe is also known to have been used by the Varangian Guard, also known as pelekyphoros phroura (πελεκυφόρος φρουρά), the "axe-bearing guard". One surviving ivory plaque from the 10th century Constantinople depicts a Varangian holding an axe that is at least as tall as its wielder.[citation needed]

Although the name retains its Scandinavian heritage, the Danish Axe became widely used throughout Europe from 12th.-13th century, as axes gained acceptance as a knightly weapon, albeit not achieving the status of the sword.[3] They also began to be used widely as an infantry polearm, with the haft lengthening to about 6 feet (1.8 m).[4][5] The 13th. and 14th. century also see form changes, with the blade also lengthening, the rear horn extending to touch or attach to the haft. The lengthened weapon, especially if combined with the lengthened blade, was called a sparth in England. Some believe this weapon is the ancestor of the halberd.[6]

While the use of the Danish Axe continued into the 14th. century, axes with an armour piercing back-spike and spear-like spike on the fore-end of the haft became more common, eventually evolving into the Pollaxe in the 15th. century.[7] The simple Danish axe continued to be used in the West of Scotland and in Ireland into the 16th. century.[8] In Ireland, it was particularly associated with Galloglas mercenaries.[9]

Famous historical figures associated with the axe

After the Battle of Stiklestad, the axe also became the symbol of St. Olaf and can still be seen on the Coat of Arms of Norway. However, this is because the axe is the implement of his martyrdom, rather than signifying use.[citation needed]

King Stephen of England famously used a Danish axe at the Battle of Lincoln 1141 after his sword broke.[10]

Richard the Lionheart was often recorded in Victorian times wielding a large war axe, though references are sometimes wildly exaggerated as befitted a national hero: "Long and long after he was quiet in his grave, his terrible battle-axe, with twenty English pounds of English steel in its mighty head..." - A Child's History of England by Charles Dickens.[11] Richard is, however, recorded as using a Danish Axe at the relief of Jaffa.[12] Geoffrey de Lusignan is another famous crusader associated with the axe.[13]

In the 14th. century, the use of axes is increasingly noted by Froissart in his Chronicle,[14] with King Jean II using one at the Battle of Poitiers in 1356 and Sir James Douglas at the Battle of Otterburn in 1388. Bretons were apparently noted axe users, with Bertrand du Guesclin and Olivier de Clisson both wielding axes in battle.[15] In these cases, we cannot tell whether the weapon was a Danish axe, or the proto-pollaxe.

See also

References

- ^ Petersen, Jan (1919). De Norske Vikingesverd. Kristiania.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ http://cache-media.britannica.com/eb-media/77/13177-004-C6966659.jpg

- ^ Edge, David (1988). Arms and Armour of the Medieval Knight. London: Defoe. pp. 31–32. ISBN 1-870981-00-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ See, for example, the illustrations in the Maciejowski Bible

- ^ "The Morgan Library & Museum Online Exhibitions - The Morgan Picture Bible". Themorgan.org. Retrieved 2012-08-20.

- ^ Oakeshott, Ewart (1980). European Weapons and Armour. Lutterworth Press. p. 47. ISBN 0-7188-2126-2.

- ^ Miles & Paddock, op.cit. p.69

- ^ Caldwell, David (1981). "Some Notes on Scottish Axes and Long Shafted Weapons". In Caldwell, David (ed.). Scottish Weapons and Fortifications 1100–1800. Edinburgh: John Donald. pp. 253–314. ISBN 0-85976-047-2.

- ^ Marsden, John (2003). Galloglas. East Linton: Tuckwell Press. ISBN 1-86232-251-1.

- ^ Oman, Sir Charles (1924). A History of the Art of War in the Middle Ages vol.1. London: Greenhill Books. p. 399. ISBN 1-85367-100-2.

- ^ Dickens is referencing Chaucer here, from the Tournament of Theseus of Athens in the Knights Tale, where a combatant "hath a sparth of twenty pound of weight"[1]

- ^ Old French Continuation of William of Tyre, in The Conquest of Jerusalem and the Third Crusade: Sources in Translation, ed. Peter W. Edbury, p. 117.

- ^ Nicholson, Helen (2004). Medieval Warfare. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan. p. 101. ISBN 0-333-76331-9.

- ^ Bourchier, John (1523). The Chronicles of Froissart. Retrieved 2009-07-28.

- ^ Vernier, Richard (2003). The Flower of Chivalry. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. pp. 72, 77. ISBN 1-84383-006-X.

Further reading

- A Warrior with a 'Danish axe' in a Byzantine Ivory Panel Article by Peter Beatson in Gouden Hoorn: Tijdschrift over Byzantium / Golden Horn: Journal of Byzantium 8(1) (2000)