Great Lillebonne mosaic

| Grande mosaïque de Lillebonne | |

|---|---|

General view of the mosaic | |

| Artist | Unknown |

| Year | 2nd-4th century |

| Dimensions | 573 cm × 592 cm (226 in × 233 in) |

| Location | Rouen (France) |

The great Lillebonne mosaic is an ancient Roman mosaic found in 1870 in Lillebonne (France), the site of the Roman city of Juliobona. It is one of the most impressive mosaic pavements discovered in France.

It originally measured 8.6 x 6.8 m[1] and is thought to date from the late 2nd or 4th century AD.

It is now conserved at the Musée des Antiquités de Rouen.

An overview of the city's ancient history

[edit]The mosaic comes from a suburban villa in present-day Lillebonne, a town located at a “crossroads on the right bank of the Seine”.[2]

Juliobona is considered the main city of the Kalete people and is mentioned as such by Ptolemy, Geography, II, 8, 5.[3]

The site shows no traces of Gallic occupation, and appears to be an Augustan foundation dating back to the reorganization of Gaul between 16 and 13 BC. At that time, the city had an “orthogonal plan adapted to topographical constraints”.

Claudius' conquest of Britannia seems to have had an impact on the development of the city, which reached its apogee between the end of the 1st and the end of the 1st century AD, a period of economic prosperity as in all the cities of Gaul.[4]

The city suffered the after-effects of the 197 power struggle between Clodius Albinus, governor of Brittany, and Septimius Severus, governor of the Danubian provinces, and underwent major restoration work.[5]

The city's port gradually silted up, and Rouen overtook it economically.[6] “The second century was thus one of slow decline for Lillebonne, accelerated by the crisis and by Saxon plundering (to which the estuary was exposed)”, with excavations showing traces of fires and the prevailing insecurity.[6]

Juliobona lost its status as a city in the 2nd century[3] and Rouen became the capital of the second Lyonnaise under Diocletian's reorganization. After the difficult period of the 2nd century invasions,[7] the site showed little sign of revival.

In the 5th century, Lillebonne shrank around a castrum built by destroying public and funerary monuments, in particular around the theater:[6] the latter was built for defensive purposes perhaps as early as 280-290, and the entire castrum was completed in the first half of the 5th century.[8]

Rediscovery and peregrinations

[edit]

Rediscovered and first interpreted by Abbé Cochet (1870-1879)

[edit]The mosaic was rediscovered at an estimated depth of between 50 and 60 cm from the ground[9] on March 8, 1870, in the Saint-Denis district,[10] on land owned by the mayor of Lillebonne, Doctor Pigné. The mosaic was discovered by a workman commissioned by the cafe owner who rented the land to transform his courtyard into a garden.[11][10]

Following a visit to the site by two members of the Société havraise d'études diverses on Sunday March 13th,[9] Abbé Cochet examined it on March 15th and 21st,[11] and gave a description later that month.[12] The work was discovered “isolated from any modern construction” and carefully cleared,[13] with “intelligent slowness”.[14]

The discovery was reported in the newspapers, even though the work had not yet been uncovered, leading to “partial descriptions and often contradictory interpretations, stemming from the inevitable trial and error of their authors, who were in a hurry to be the first to arrive ”.[14] Bouet surveyed the mosaic, while Duval, a tax collector from Lillebonne,[15] produced a watercolor reproduction.[16]

As a result of the discovery of terracotta statuettes for religious purposes during the excavation of the mosaic, Abbé Cochet indicated in 1870 that “the building, of which we have the paving, was a temple dedicated to Diana and Apollo”.[17] However, this was an abusive interpretation, reflecting a “method of architectural identification based simply on iconographic considerations” according to Harmand, the 20th-century excavator of the site.[18]

The original edifice is thought to have been destroyed by fire, as Abbé Cochet notes that “over the entire mosaic was a black, charcoal layer several centimeters thick ‘,[13] in which were found ’terracotta statuettes, broken or whole” representing seated figures.[19] The site was covered with fragments of tile, and roofing nails were also discovered.[13]

Once cleared, the mosaic was summarily displayed at the site of its discovery, under a shed, and was for a time accessible to the public. Ownership of the mosaic was disputed between the landowner and the workman, and the 1879 judgement was in favor of the landowner.[1]

Sales and trip to Russia (1879-1885)

[edit]

The work was deposited[20] and sold for the first time in August 1879 to Mme Merle for 20,000 or 23,500 francs,[21] after unsuccessful bids by the Seine-Inférieure department, supported in particular by Abbé Cochet[3] and for the Musée des Antiquités de Rouen.

The work was deposited by Giandomenico Facchina, a renowned Italian mosaicist (he had been involved in decorating the Garnier opera house in particular),[22] assisted by three Italians and two Frenchmen (an engineer and an architect). The mosaic left its city of origin in various crates on July 1, 1880.[3]

The mosaic was restored between 1880 and 1885 by two successive restorers: Facchina in 1880-1881 (this restoration would have been expensive, costing 12,000 francs[2]), and Zanussi, heir to the Mazzioli-Chauviret firm, in 1883-1885. Zanussi was commissioned to reassemble the work at the Musée de Rouen before a second sale.[23]

It was sent in 60 fragments to Russia,[24] perhaps to be sold there,[25] but apparently in vain, as no business was concluded during this journey,[1] or at least no overall sale, although Darmon's work suggests that authentic elements were removed during this journey.

On the mosaic's return to France, it was restored for sale by “Italian mosaicists of identical training and experience, heirs to the modern Italian tradition”.[25]

It was displayed in 22 fragments and auctioned at Hôtel Drouot on May 16, 1885.[26][1] The Musée du Louvre and the Musée des antiquités nationales de Saint-Germain-en-Laye refused to acquire it,[24] perhaps due to the manoeuvring of the curator of the Musée des Antiquités de Rouen, Maillet du Boullay. The work was sold for 7,245 francs, including costs, although it had been appraised at 100,000 francs,[27] with initial purchase and restoration costs of around 30,000 francs.[28]

Exhibition at the Musée des Antiquités de Rouen (since 1886)

[edit]

After being restored once again, it joined the collections of the Musée des Antiquités de Rouen in 1886[20] (and not from the year of its discovery, contrary to what is sometimes claimed[29]), in a room specially designed for it, “worthy of housing the mosaic”.[2] Significant modifications were made in 1954.[30]

The current presentation at the Musée des Antiquités de Rouen features a connection with a geometric decoration that is not the original one, but is the result of a restoration in 1886[20] or a remounting dated 1954, during the latest refurbishment of the museum's mosaic and sculpture room.[30] According to Darmon, this geometric decoration comes from another discovery made in Lillebonne in 1836, preserved in the Musée des Antiquités and then mistakenly attached to the mosaic.[31] Certain restorations and modern additions are also highly suspect, in particular the heads of the figures, which certainly look modern and thus prove that original elements were dispersed during the work's peregrinations.[32]

Excavations and a new interpretation by Harmand

[edit]The villa from which the mosaic originates was excavated by Louis Harmand in October 1964, April and October 1965.[18][33] The excavator's work was hampered by modern constructions, and investigations were limited,[34] in particular due to the destruction of archaeological layers.[35]

Harmand confirmed that the building had no religious purpose and was not a fanum[36] but a villa; however, this excavation did not include a systematic survey of the building plan[24] and did not reveal any elements left in place during previous excavations of the large mosaic.[30]

Despite this, the excavation revealed that the villa's other rooms, including “cramped, secluded corner rooms ”,[36] were almost all fitted with red painted plaster and also with plaster with geometric decor,[24] including alternating green, red and ochre panels.

Some painted elements were still in situ on the remains of walls preserved to a height of only 0.25 m to 0.30 m.[36] The excavators found traces of red frescoes “except in a corner room of the front gallery ”.[12]The villa in which the mosaic was discovered is estimated to date from the second half of the 2nd century.[37] The villa had a front gallery (similar to the villa with the large peristyle at Vieux-la-Romaine) and a corner tower.[38] According to Michel de Boüard, the villa's plan was of a widespread and stereotyped type, “a large rectangle 15 to 20 m long by 8 to 10 m deep, with variable internal partitioning”; a large room has corridors opening onto the façade, which is equipped with a portico.[39] Harmand identifies the excavated building with a well-known model such as the villa at Maulévrier or Lébisey[40] in Hérouville-Saint-Clair. According to Harmand, the villa measured 18 m from north to south.[41]

The building was heated not by the floor but by terracotta elements installed in the partitions, and great care was taken to avoid heat loss.[42] Excavations in 1964 revealed tegulæ mammatæ and tubuli[34] and, in 1965, elements of the præfurnium were uncovered.[35]

The building's owner was prosperous, and the mosaic adorned a dining room (triclinium) that was equipped with ceremonial beds.[43] In the adjoining room, however, the floor was covered with a crude pavement, using “the most elementary coating processes”, with “flat stone elements and tile splinters juxtaposed”.[42] The triclinium also featured painted and marble[12] decorations, fragments of which were found during the first excavations.[13] The walls were very flat, only “a few centimetres ”[13] high and around 60 cm thick.[12][2]

Description

[edit]

The mosaic was found with a number of gaps, identifiable by a photograph taken in 1870. Although heavily altered, the mosaic is well preserved and depicts deer bellowing in a “remarkable thematic unity”,[43] and in a wooded landscape reminiscent of the forests of Normandy,[44] decked out in the colors of autumn, with tesserae ranging from yellow to red.[45]

The mosaic was present in the triclinium, the villa's dining room, in a classic T and U configuration.[notes 1][29][12] The entrance to the room was to the east.[46]

According to Abbé Cochet,[13] the paving measured a total of 8.50 m by 6.80 m at its maximum. Cochet emphasizes the quality of the cement used to form the mosaic base, which “largely explains the good preservation of the paving”.[47] According to Abbé Cochet,[13] the area bearing the figurative panels measures 5.80 m long by 5.60 m wide, but is now 5.73 m by 5.92 m.[30]

In addition to a fairly common geometric mat, it features a central motif measuring 2.55 m by 2.75 m, surrounded by four 1.20 m trapezoids.[17][48][29] The part with figurative scenes was enclosed in a U-shaped border, white and black and 0.55 cm wide.[1]

In the foreground geometric motifs

[edit]The foreground is occupied by a geometric carpet of intersecting circles,[1] which is not the main interest of the work.[49]

At the time of its discovery, this section, which contains “on a white background, interlocking red circles”, measured 6.70 m long by 2.50 m wide according to Abbé Cochet[13] and 2.25 m according to Darmon.[1]

The geometrically-decorated mosaic on display at the Musée des Antiquités does not correspond to the descriptions at the time of discovery, but to another Lillebonne work unearthed in 1836. Its elements “were wrongly combined with the large Lillebonne mosaic when it was transferred in 1954”.[46]

We still don't know what happened to this part of the work, which was deposited in 1880[46] because, according to Darmon, “no fragment of the geometric carpet of the original extension” remains in the Rouen museum.[31] Darmon evokes the possibility of either a deposit in a private collection or the loss of the motif as “deemed unworthy of preservation ”.[31]

Side patterns

[edit]Each trapeze depicts a hunting scene in a wooded landscape.

One of the trapezes has been called a “propitiatory sacrifice to Diana before setting off on a slab hunt ”.[24] It depicts a sacrifice to the goddess of the hunt, Diana, who stands on a circular pedestal[30] and is traditionally depicted wearing a tunic, sandals, a bow in her left hand and drawing an arrow from her quiver with her right hand.[50][51] The tesserae used to represent the goddess are coloured to evoke bronze.[30]

The scene also features an altar with pieces of wood for the sacrificial fire,[52] the forest suggested by the vegetation between the various figures.[24]

A man, the officiant, points to the statue of the deity with his right hand, “perhaps the end of a ritual kissing gesture”.[52] Other figures are shown to the right and left of the goddess: these include a young server behind the altar, a man holding a dog on a leash and a spear, and a man holding the reins of a horse and a whip.[52] To Diana's right, an officiant (or another server, according to Darmon[52]) points to the representation of the deity; he holds a patera and an oenochoe; another individual holds a stag[37][51] in both hands.[52]

The composition is meticulous, “harmonious, with an effect of both symmetry and variety ‘:[52] the goddess occupies the center of the panel, and there is a symmetry between the man with the horse on the left and the man with the stag on the right, with the other figures on either side of the altar and pedestal on which the representation of the divinity is enthroned, ’the axis of the painting”.[24] The landscape is evoked by the vegetation integrated into the composition, and the ground and shadows of the protagonists are suggested by the use of ochre tesserae.[52]

The other trapezoids depict the departure for the hunt, the hunt for the decoy and a hunting scene.

Departure for the hunt

[edit]

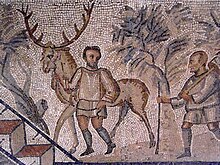

The scene of departure for the hunt depicts a line of people and animals in a bushy landscape, moving towards the left.[52]

From right to left are two horsemen, a man with a stick and a cylindrical object, followed by two dogs.[52] The cylindrical object has been mistaken “for a club used to stun the stag, for a hammer to fix a stake to the ground, for a skin-covered drum” or even for an element designed to illuminate the hunting scene; Yvart, for his part, adheres to the hypothesis of an utensil intended for hunting, to “roll up a battue streamer”.[53] On the left is a stag held by a man with a bridle.[54]

The rider furthest to the right is riding a horse and holding a whip, while the second is about to mount53.[52] One of the two riders has been heavily reworked in the modern restoration, and his posture is now “strange and stilted”, whereas the original position was a more fluid movement, “evoking the posture of a galloping rider trying to look behind, and of an infinitely happier effect than what we see represented today”.[55]

Ride

[edit]

The so-called “chasse à courre” scene depicts three horsemen, accompanied by their dogs, riding towards the area where the bow-wielding master is stationed. This is undoubtedly “the noisy ride of the beaters ”.[28] Yvart considers this panel to be unrelated to hunting with a decoy, and identifies it as a hounding scene, even though he considers some of the hunters to be the same protagonists as the bellowing scene54.[53]

The scene is energized by movement from left to right57.[56] This is emphasized by the way in which the riders and their mounts are depicted (the last of which is represented only by its forequarters) and the dogs, the first of which is leaping and depicted as a very large animal58,57.[57][56]

One of the riders has been clumsily restored, for which “the restorer did not understand the position” intended by the artist. The figure was holding a whip and reins while turning around57.[56] The attributes of the other rider may have been altered by the restorer57.[56]

Caller hunt

[edit]

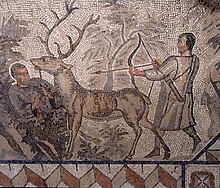

Hunting with bellowing or calling “evokes a Gallic hunting practice ”52:[51] in the middle of the panel we see a thick bush57;[56] on the left, two hinds, of which only the forequarters can be seen, emerge from a bush, and in front of them is a large stag.[56]

This large stag is about to be trapped by a crouching man[51] dressed in a white tunic,[56] who has already captured one of his now tame congeners[37][57] and is holding it by means of a tether.[58] This second stag serves as bait and “appears agitated and feverish”, “animated by a movement difficult to contain ”,[56] perhaps due to the majesty of the wild animal he is confronted with. The captive animal is ready to bellow, according to Yvart.[53] An archer (carrying a double-curved weapon [59]), positioned behind the domesticated stag, is about to release an arrow in the direction of the wild stag,[56][57] which is in rut, and is represented in the posture specific to this period, with its neck swollen and the coloring of its coat.[53] According to Yvart, this last element is a sign of “Gallo-Roman realistic art”.[53] The wild animal is about to be slaughtered.[28]

The figures depicted are of two types, identified by their clothing and shoes:[51] the hunters are dressed in a wide, loose tunic “close to the loose garment characteristic of the Gauls” according to E. Deniaux, “richly adorned masters”,[51] while the servants are clad in a shorter tunic.[37] Deniaux, “richly adorned masters”,[51] while servants wore a shorter tunic.[37]

This technique of hunting tamed deer is characteristic of Gallic or Germanic tradition according to Darmon,[28] but “widespread in the Roman world” according to Yvart,[60] although the style of the mosaic is Roman. According to Yvart, the hunting season could only have taken place during the deer's short rut in early autumn.[61] Representations of such scenes are rare, but Yvart mentions an arkose bas-relief preserved in the Musée Crozatier in Le Puy-en-Velay,[45] which bears an early depiction of a crossbow, a weapon known from the texts of Vegece.[59] He also refers to a vase found at Alise-Sainte-Reine bearing a scene of the same theme.[58]

The central pattern

[edit]

The central space consists of a square measuring 2.55 m by 2.75 m[30] within which is inscribed a circle bearing a scene, with a spandrel in each corner. A mythological motif is depicted in the circle, as are palms,[62] symbolizing victory, and cups in each corner,[29] probably gold canthars filled with wine.[57][56]

The central painting was very incomplete at the time of discovery, and the extent of the lacunae in the ancient documents underlines the arbitrariness of the restoration carried out at the end of the 19th century.[63]

The mythological motif features an almost-naked woman surrounded by a veil suspended above her and enveloping her thighs, with an urn in her right hand and her left arm extended as well as her hand towards a male figure, “as if in a gesture of imploration”, also wrapped in a cloth and whose left hand held an ill-identified object, scepter or thyrse.[62] The male figure comes from the right in a lively movement, and has undergone numerous restorations, with the restorer retaining a bias that is not necessarily that of the original, due to the deterioration of the figure on discovery.[62]

The identification of the characters is not guaranteed,[28] as those proposed do not correspond to known treatments: Amymone surprised by Poseidon (who is missing his trident, the usual attribute of the marine divinity[56]), the woman does not appear to be a representation of Daphne or Callistô. Another proposed interpretation is the meeting of Dionysus and Ariadne, “treated in an unusual manner” even though the cups are filled with wine,[57] the latter identification being the one preferred by Darmon.[28] Nor does the male figure appear to be Apollo,[28] contrary to Yvart's identification of the scene as Daphne being pursued by Apollo.[58]

However, the artist's aim is understood, in a “unity of intent ‘,[64] ’the theme of the hunt metaphorically illustrating that of the pursuit of love”.[57] The representation of palms and canthars evokes victory in the hunt and can also be transposed to the realm of love.[64]

Two inscriptions, AE 1978, 00500 and CIL XIII, 3225, each two lines long and unclear, appear in the medallion and in a cartouche ending in a dovetail.[48][62]

First line: T(itus) Sen(nius) [or Sextius] Felix c(ivis) pu/teolanus fec(it): Titus Sennius Felix citizen of Pozzuoli made (or had made) [this mosaic].

Titus Sennius Felix is either the artist or the commissioner of the work, the verb facio meaning both “to make” and “to have made ”.[27] Darmon considers that “in the current state of research [...] T. Sen. Felix designating the patron“.[64]

This first inscription has been interpreted in this way since the work of Abbé Cochet.[65]

Second line: (e)t Amor c(ivis) K(aletorum)/ discipulus: et Amor, citoyen de la cité des Calètes, son élève. Some believe it can also be expanded to c(ivis) K(arthaginiensis) (Carthage).

Michel de Boüard considers the work “the most splendid mosaic (...) [as] probably due to the collaboration of an artist from Pozzuoli and a Caleta, his pupil and apprentice”.[66]

The meaning continues to raise questions,[57] all the more so as the disciple, also a Roman citizen, should have been named with his tria nomina. Perhaps this inscription makes sense in view of the theme of the pursuit of love.[64] The inscription may have been damaged “when it was removed ”.[62]

Difficulties and interpretation

[edit]Difficult interpretation of a heavily reworked work

[edit]Many gaps in discovery

[edit]

At the time of its discovery, the mosaic had gaps in the central medallion and in the details of certain trapezoids, as attested by documents dating from the time of discovery, the most valuable of which is a retouched photograph.[67][68] These gaps were filled in 1880, “with unequal happiness”.[47]

The biggest gaps were in the central panel, where the figures had been damaged, and three of the four side panels were also missing.[69] “The corresponding parts of the mosaic in its current state are therefore modern”, according to Darmon.[69]

Restorations sometimes untimely

[edit]

The restorations are of uneven quality, as is their insertion into the antique work, with both skilful repeats and errors, including an “arbitrary assumption” or inaccuracies concerning the colors of the tesserae used for the restoration,[70] or even clumsiness - such as that of the rider in the side panel of horses and hounds.[71] The central panel was extensively reworked, as there were significant gaps, but the restoration work was carried out with care, as “the most scrupulous examination (...) does not reveal their exact limits”.[64]

Some of the figures' heads are no longer antique, and Darmon's work demonstrates the untimely interventions carried out in the 19th century, including “almost all the faces of the figures in the trapezoidal panels ”.[47] An early photograph reveals that some of the heads “are entirely in keeping with the habits of ancient mosaicists, the technique is tachist, more concerned with painting than drawing, (...) rendering [the] volumes in the form of a series of lines. ) render[ing] volumes by playing on oppositions of colors and tones using fairly large tesserae, with a very happy result", whereas today's heads are made from small tesserae with an unhappy result, ‘the naïve verism and dulcet softness being much more akin to St. Sulpician aesthetics than to antique art.[72][47]

The changes made to the work are linked either to deterioration during successive deposits, or to fraud: when the work was sent to Russia, certain heads were sold separately,[32] replaced in preparation for the 1885 sale by others made “not according to ancient art, but according to the techniques of nineteenth-century Italians trained in the Ravenna school, the Renaissance and Sulpician art ”.[24] Darmon emphasizes that “the originality of the fraud would here be the insertion of small false parts into an authentic whole, to replace the corresponding authentic fragments which would themselves have been sold separately”.[73][28]

A mosaic head supposedly from Lillebonne and preserved in the Musée d'Autun is a modern forgery, reflecting the practice of the period.[32] Several of the heads in the present work have the “same sweet, frozen expression, so characteristic”, and the plants and animals seem to have been little altered, according to Darmon.[32] "It remains to be seen where the authentic heads, which would have been sold between 1880 and 1885, are kept”.[28]

Dating and interpretation

[edit]Dating not yet certain

[edit]

Darmon dates the work to the first century and considers it contemporary with the Lillebonne theater and “the work of an Italian artist, [...] a mosaic artist from Pozzuoli, trained in the best schools of his time”.[74] Yvart considers that the mosaic undoubtedly dates from the heyday of the city of Lillebonne.[45] Chatel considers that the building was a “pagan sacellum”.[15] These interpretations are old and cannot be accepted as they stand today, especially after the excavations carried out by Harmand in 1964-1965.[18] Some elements point to a later date: “the very coarse treatment of the drapery floating around the god” and “the very crude heaviness of the thick border motif ”.[64] However, archaeologists have found little evidence of a resumption of activity after the 2nd century, and tria nomina are now rarely used except for very important figures.[7]

With the doubts permitted by the current state of knowledge, Darmon proposes a range from the 2nd century to the first half of the 4th century.[7]

Testimony to aristocratic lifestyle

[edit]

Along with other ancient discoveries in Normandy, such as the Berthouville treasure and the Thorigny marble, the great Lillebonne mosaic bears witness to the Romanization of the area of future Normandy: the river undoubtedly played a role as an axis for the penetration of Roman influences, according to E. Deniaux. Deniaux.[29]

The work bears witness to the wealth of local notables, like the painted decorations found in the excavations of the archaeological garden of the Lisieux hospital29 or like certain painted decorations found to a lesser degree in Bayeux and now on display at the Musée Baron Gérard. “Testifying to the costumes, customs and leisure activities of a number of important figures,[61] the scenes depicted are representative of the iconography found in aristocratic homes, with the ’evocation of an aristocratic lifestyle in which the nobleman asserts his superiority through his equipment and activity”, but with an adaptation to the local context,[37] in particular the depiction of Norman forests.[75]

See also

[edit]- History of Normandy

- Villa Romana del Casale

- Neptune Triumph and the House of Sorothus mosaic

- Carthage Circus Mosaic

Notes

[edit]- ^ The U was formed by a mosaic carpet of white tesserae 0.55 cm wide; the T was formed by the geometric carpet bar and the mosaic panel featuring the circle with the divinity and the trapezoids of the hunting scenes.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Darmon (1994, p. 92)

- ^ a b c d Deniaux et al. (2002, p. 80)

- ^ a b c d Rogeret (1997, p. 326)

- ^ Rogeret (1997, p. 328)

- ^ Rogeret (1997, pp. 328–329)

- ^ a b c Rogeret (1997, p. 329)

- ^ a b c Darmon (1994, p. 102)

- ^ Rogeret (1997, p. 389)

- ^ a b Chatel (1873, p. 571)

- ^ a b Darmon (1994, p. 90)

- ^ a b Cochet (1870, p. 37)

- ^ a b c d e Rogeret (1997, p. 367)

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cochet (1870, p. 38)

- ^ a b Chatel (1873, p. 572)

- ^ a b Chatel (1873, p. 573)

- ^ Chatel (1873, p. 574)

- ^ a b Cochet (1870, p. 39)

- ^ a b c Harmand (1965, p. 65)

- ^ Cochet (1870, pp. 38–39)

- ^ a b c Darmon (1978, p. 66)

- ^ Darmon (1978, p. 86)

- ^ Darmon (1978, pp. 81–83)

- ^ Darmon (1978, p. 83)

- ^ a b c d e f g h Rogeret (1997, p. 368)

- ^ a b Darmon (1978, p. 84)

- ^ Darmon (1978, p. 81)

- ^ a b Darmon (1978, p. 87)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Darmon (1994, p. 100)

- ^ a b c d e Deniaux et al. (2002, p. 193)

- ^ a b c d e f g Darmon (1994, p. 93)

- ^ a b c Darmon (1978, p. 67)

- ^ a b c d Darmon (1978, p. 79)

- ^ Rogeret (1997, pp. 366–367)

- ^ a b Harmand (1965, p. 67)

- ^ a b Harmand (1965, p. 68)

- ^ a b c Harmand (1965, p. 66)

- ^ a b c d e f Deniaux et al. (2002, p. 195)

- ^ Rogeret (1997, p. 366)

- ^ de Boüard (1970, p. 63)

- ^ Harmand (1965, p. 71)

- ^ Harmand (1965, p. 69)

- ^ a b de Boüard (1970, p. 65)

- ^ a b Leménorel (2004, p. 56)

- ^ Leménorel (2004, pp. 56–57)

- ^ a b c Yvart (1959, p. 38)

- ^ a b c Darmon (1994, p. 99)

- ^ a b c d Darmon (1994, p. 99)

- ^ a b Deniaux et al. (2002, p. 194)

- ^ Deniaux et al. (2002, p. 194)

- ^ Deniaux et al. (2002, pp. 193–195)

- ^ a b c d e f g Leménorel (2004, p. 57)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Darmon (1994, p. 94)

- ^ a b c d e Yvart (1959, p. 37)

- ^ Rogeret (1997, pp. 369–370)

- ^ Darmon (1978, pp. 73–74)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Darmon (1994, p. 95)

- ^ a b c d e f g Rogeret (1997, p. 370)

- ^ a b c Yvart (1959, p. 36)

- ^ a b Yvart (1959, p. 39)

- ^ Yvart (1959, p. 40)

- ^ a b Yvart (1959, pp. 37–38)

- ^ a b c d e Darmon (1994, p. 96)

- ^ Darmon (1978, p. 74)

- ^ a b c d e f Darmon (1994, p. 101)

- ^ Cochet (1870, p. 44)

- ^ de Boüard (1970, p. 64)

- ^ Darmon (1978, pp. 69–70)

- ^ Darmon (1994, p. 99)

- ^ a b Darmon (1978, p. 71)

- ^ Darmon (1978, p. 72)

- ^ Darmon (1978, p. 73)

- ^ Darmon (1978, p. 76)

- ^ Darmon (1978, p. 85)

- ^ Cochet (1870, pp. 44–45)

- ^ Groud-Cordray (2007, p. 14)

Bibliography

[edit]- Baratte, François (1996). Histoire de l'art antique: L'art romain (978-2-711-83524-9 ed.). Paris: Manuels de l’école du Louvre - La documentation française.

- Darmon, Jean-Pierre (1994). Recueil général des mosaïques de Gaule, province de Lyonnaise: 10e supplément à Gallia, vol. 5. CNRS.

- Demarolle, Jeanne-Marie. à la recherche des métiers d'art en Gaule et en Germanie romaines.

- Rogeret, Isabelle (1997). La Seine-Maritime, Paris, Ministère de l'enseignement supérieur et de la recherche ; diff. Fondation Maison des sciences de l'homme. Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres, Ministère de la culture. ISBN 2877540553.

- Sennequier, Geneviève (2002). Les mosaïques du Musée départemental des Antiquités. Département de Seine-Maritime.

- Vipard, Pascal (2012). La (future) Normandie dans l'espace nord-occidental d'après les sources écrites antiques des Ier-IVe siècles », dans Jérémie Chameroy et Pierre-Marie Guihard, Circulations monétaires et réseaux d'échanges en Normandie et dans le Nord-Ouest européen (Antiquité-Moyen Âge). Caen. ISBN 9782841334209.

- Deniaux, Elisabeth; Lorren, Claude; Bauduin, Pierre; Jarry, Thomas (2002). La Normandie avant les Normands: de la conquête romaine à l'arrivée des Vikings. Rennes. ISBN 2737311179.

- Groud-Cordray, Claude (2007). La Normandie gallo-romaine, Cully. Orep éditions. ISBN 978-2-915762-18-1.

- Leménorel, Alain (2004). Nouvelle histoire de la Normandie, Toulouse. Privat. ISBN 9782708947788.

- Rouen T1: de Rotomagus à Rollon. Éditions Petit à Petit. 2015.

- de Boüard, Michel (1970). Histoire de la Normandie, Toulouse. Privat.

- Chatel, Eugène (1873). Notice sur la mosaïque de Lillebonne. Mémoires de la Société des antiquaires de Normandie.

- Cochet, Jean-Benoît-Désiré (1870). Sur la mosaïque de Lillebonne. CRAI.

- Darmon, Jean-Pierre (1976). La mosaïque de Lillebonne. Musée des Antiquités.

- Darmon, Jean-Pierre (1978). Les restaurations modernes de la grande mosaïque de Lillebonne (Seine-Maritime). Gallia.

- Harmand, Louis (1965). La « villa de la mosaïque » à Lillebonne. Revue des Sociétés Savantes de Haute-Normandie. Préhistoire-Archéologie.

- Yvart, Maurice (1959). Aperçus nouveaux sur la mosaïque de Lillebonne. Revue des Sociétés Savantes de Haute Normandie.

- (Collectif) (1885). Grande mosaïque de Lillebonne (Seine Inférieure) dont la vente aux enchères publiques aura lieu Hôtel des Commisseurs-priseurs, rue Drouot... Exposition publique... par le ministère de Me Albinet... assisté de MM. Rollin et Feuardent, experts, Paris.

- (Collectif) (1871). La mosaïque de Lillebonne - Extrait des Publications de la Société Havraise d'Études diverses. - Deux lettres de M. Ch. Roessler et de M.A. Longpérier, Rouen.