Jerome Hall

Jerome Hall | |

|---|---|

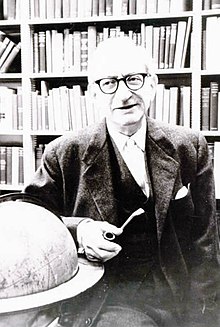

Professor Hall at Indiana University, circa 1970 | |

| Born | February 4, 1901 Chicago, Illinois |

| Died | March 2, 1992 (aged 91) San Francisco, California |

| Education | University of Chicago |

| Occupation | Professor of Law |

Jerome Hall (February 4, 1901 – March 2, 1992) was an American legal scholar and academic. He is best known for his pioneering work in interdisciplinary legal analysis. Through his work with the United States Department of State, he offered advice and insight to several countries across the globe as they rewrote some or all of their legal codes.

Early years and education

[edit]Hall was born in 1901 and grew up in Chicago, Illinois. He studied at the University of Chicago and was a Fulbright scholar, earning both his bachelor's in philosophy and his law degrees. He graduated from law school with honors in 1923.[1]

Career

[edit]Hall became a member of the Illinois Bar in 1923, and began his legal career practicing corporate law in Chicago from 1923 to 1929. Even during this early stage of his career, the allure of teaching manifested itself, and he began teaching classes in public speaking and business law at the Indiana University Extension (now Indiana University Northwest) in Gary, Indiana.[2] These early teaching experiences fostered a love of teaching, and in 1929, he left his legal practice behind to teach full time, beginning at the University of North Dakota from 1929 to 1932.[3] From 1932 to 1934 he taught as a special fellow at Columbia University, earning his Doctor of the Science of Law (Jur.Sc.D.) in 1935.[4] From 1934 to 1935 he taught as a Benjamin Research Fellow at Harvard Law School, earning the degree of Doctor of Juridical Science (S.J.D.) in 1935.[4] He next moved to Louisiana State University and taught as a professor of law from 1935-1939, before moving to Indiana.[4] Hall spent the majority of his professional career as a professor of law at Indiana University Bloomington from 1939 to 1970. Upon retiring at 65, he was invited to join the esteemed Sixty-Five Club at University of California, Hastings College of the Law, where he continued to teach until 1986.[5]

Scholarship

[edit]Hall was a renowned scholar in comparative law, criminal law, and jurisprudence. He was among the first scholars to analyze legal problems through an interdisciplinary approach. He published his first book, Theft, Law and Society, in 1935; even then his interdisciplinary approach to legal analysis could be seen: "One great effect is and will be the fact that it stimulates one's thinking along all the allied fields…. The author realizes that crime is behavior. If those who defend individualization of punishment and those who are sceptical [sic] of all individualization of punishment will read this chapter, I think that there will be much more sense displayed in the writing and the talking on this subject."[6] In one of his best known works, General Principles of Criminal Law, Hall developed a single concept of mens rea,[7] a common law principle today regarded as a critical element of proving culpability for a crime. Readings in Jurisprudence, first published in 1938, has seen multiple editions and was popular both in the United States and in England.[8] His writings on criminal law theory became well known among scholars. "Professor Hall has added another book to his already long list of distinguished publications. [Studies in Jurisprudence and Criminal Theory] is not a self-contained segment of work, but, rather, a cross section of works, and not just of any scholar, but of an unusually original thinker. Moreover, the subjects joined in this book have rarely, if ever, been combined in this country. The result of this joinder is a new area of inquiry, criminal theory."[9] Late in his career, Hall's research interests shifted to a focus on law and religion, and he became involved with the Harvard Divinity School and Berkeley's Pacific School of Religion, speaking and writing on the topic; through this new interest, he was asked to be a founding member of the Association of American Law Schools' Section on Law and Religion, and was the first director of the Council on Religion and Law, a non-profit organization that came out of a series of discussions and conferences at Harvard in the 1970s.[10] A full bibliography of his written works can be found on the Jerome Hall Law Library website.

Professional Contributions

[edit]Hall made significant contributions to the global legal community throughout his career. He was an active member of several professional organizations, including serving as chairman and editor of the Modern Legal Philosophy Series from 1940 to 1956,[11] and holding simultaneous presidencies of both the American Society for Political and Legal Philosophy and the American section of the International Association for Philosophy of Law and Social Philosophy, 1965-66.[12] In 1954, Hall was one of two Americans approached by the US Department of State to travel to Korea to assist the country in reconstructing their legal system.[13] He spent seven weeks in Korea, then went to Japan for another six weeks, and was then asked to continue on to India for another six weeks, culminating in the Philippines for an additional week. He was named honorary director of the Korean Law Institute in 1955. The State Department came to him a second time in 1968 and asked him to lecture across Asia as a "leader specialist" in the US State Department's Exchange Program. He advised India on the rewriting of the country's criminal code during this trip.[2]

Hall's international lectureship did not end with his involvement with the US Department of State. He has held several prestigious lecturer positions at universities across the globe, including a Fulbright Scholar position at the University of London and Queen's University in Belfast from 1954–55; a Ford Foundation lectureship in 1960 that sent him to Mexico and several countries in South America; a second Fulbright Scholar position in 1961 at Freiburg University; and a Rockefeller Foundation grant to study and lecture on comparative law in Western Europe from 1961 to 1962.[2]

Hall's teaching accolades could be seen within the United States as well. He received the Frederic Bachman Lieber Memorial Award for distinguished teaching from Indiana University in 1956; Hall was only the second recipient of this award, and was the only law professor at IU to receive it during his career.[14] He attained the faculty ranking of distinguished professor at Indiana University in 1957.[15] He later held the Edward Douglass White lectureship at Louisiana State University in the spring of 1962 and was a Murray Lecturer at the University of Iowa in 1963.[16] Upon his retirement, he was invited to join the prestigious Sixty-Five Club at the University of California Hastings College of the Law, a club that invited distinguished law professors to continue their teaching and scholarly pursuits as members of the Hastings faculty upon retirement.[17]

Awards and honors

[edit]Hall received several honorary doctor of law degrees throughout this career: from the University of North Dakota in 1958,[18] the China Academy in Taipei in 1968,[19] and the Tuebingen University in 1978.[20] In addition, he was bestowed with the Order of San Francisco by the University of Sao Paulo, Brazil, was made honorary president of the Latin American Association of Sociology, and became an honorary member of the bar associations of Arequipa, Peru, LaPaz, and Bolivia in 1960. In 1976, he became the first recipient of the 1066 Foundation's Distinguished Professorship Award.[21] In 1986, he became an honorary member of the American Society for Political and Legal Philosophy.[2] He was one of 25,000 people whose biography appeared in the first edition of Marquis' Who's Who in the World (1972).[22]

Personal life

[edit]In 1940, Hall married Marianne Adele Cowan, an actress from Fort Wayne, Indiana. Classically trained at London's Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, Marianne had performed in New York, Philadelphia, and Canada. She died in 1980. They had one daughter, Heather, who became a teacher.[5]

Legacy

[edit]Jerome Hall died in 1992.[8] His scholarship continues to have an influence, cited regularly in academia today. Indiana University Maurer School of Law's Center for Law, Society, and Culture continues Hall's work in interdisciplinary analysis of legal problems by bringing together scholars from departments and schools across campus to engage in collaborative research and scholarship. In 2015, Lowell E. Baier, a 1964 graduate of Indiana University School of Law in Bloomington, Indiana, and former student and research assistant of Hall,[23] gave a substantial gift to the law school and had the law library named the Jerome Hall Law Library, in honor of his professor and mentor.[24]

References

[edit]- ^ "Citation: Jerome Hall," 35 N.D. L. Rev. 89 (1959).

- ^ a b c d Dorothy Mackay-Collins. "Oral History with Professor Jerome Hall." University of California Hastings College of the Law (June 17, 1987).

- ^ Mackay-Collins at 9.

- ^ a b c Eloise Helwig. "1066 Foundation Honors Jerome Hall." Hastings Law Bulletin volume XXI number 1 (Fall 1976).

- ^ a b Mackay-Collins at 17.

- ^ Paul J. Mundle. "Book Review: Theft, Law and Society, By Jerome Hall." 19 Marq. L. Rev. 146 (1935).

- ^ Livingston Hall. "Review: General Principles of Criminal Law, by Jerome Hall." 60 Harv. L. Rev. 846 (1946-47) ("The most distinctive contribution made by Hall to criminal theory lies in his development of a single concept of mens rea." (page 848)).

- ^ a b Wolfgang Saxon. "Obituary: Jerome Hall, 91, Legal Scholar Who Was Professor and Author." New York Times (Mar. 11, 1992).

- ^ Gerhard O.W. Mueller. "Criminal Theory: An Appraisal of Jerome Hall's Studies in Jurisprudence and Criminal Theory." 34 Ind. L. Rev. 206 (1958-59).

- ^ Mackay-Collins at 96.

- ^ Mackay-Collins at 30.

- ^ "Jerome Hall, 1901-1992." Hastings Community (Summer 1992).

- ^ Robert G. Storey. "Korean Law and Lawyers: The New Korean Legal Center." 41 American Bar Association Journal 629 (1955).

- ^ Mackay-Collins at 70.

- ^ "Jerome Hall Ends 31-Year Teaching Career at IU." 2 Bill of Particulars 7 (1970).

- ^ Mackay-Collins at 72, 73.

- ^ Sixty-Five Club Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ O.H. Thormodsgard. "Citation: Jerome Hall." 35 N.D. L. Rev. 89 (1959).

- ^ Mackay-Collins at 40.

- ^ Mackay-Collins at 111.

- ^ Eloise Helwig. "1066 Foundation Honors Jerome Hall." 21 Hastings Bulletin 23 (1976).

- ^ "Faculty Focus: Professor Jerome Hall." 17 Hastings Alumni Bulletin 11 (1972).

- ^ Lowell E. Baier. "Dr. Jerome Hall: A North Star in My Life." 81 Ind. L.J. 465 (Spring 2006) (describing the experience of having Hall as a teacher and mentor).

- ^ "Indiana University Maurer School of Law Announces $20 Million Gift Archived 2016-07-31 at the Wayback Machine." Press Release. (March 25, 2015).

External links

[edit]- Jerome Hall Law Library Archived 2015-12-07 at the Wayback Machine