Eduard Pernkopf

Eduard Pernkopf | |

|---|---|

Eduard Pernkopf in academic regalia. | |

| Born | 24 November 1888 |

| Died | 17 April 1955 (aged 66) Vienna, Austria |

| Nationality | Austrian |

| Alma mater | University of Vienna |

| Known for | Topographische Anatomie des Menschen, anatomical atlas possibly derived from executed Nazi political prisoners |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Anatomy |

Eduard Pernkopf (November 24, 1888 – April 17, 1955) was an Austrian professor of anatomy who later served as rector of the University of Vienna, his alma mater. He is best known for his seven-volume anatomical atlas, Topographische Anatomie des Menschen (translated as Atlas of Topographical and Applied Human Anatomy; often colloquially known as the Pernkopf atlas or just Pernkopf), prepared by Pernkopf and four artists over a 20-year period.[1] While it is considered a scientific and artistic masterpiece,[2] with many of its color plates reprinted in other publications and textbooks, it has been in recent years dogged by questions about whether Pernkopf and the artists working for him, all of them ardent Nazis, used concentration camp inmates or condemned political prisoners as their subjects.

Early life

Pernkopf was born in 1888 in the Lower Austria village of Rappottenstein, near the border with Bavaria. The youngest of three sons, he seemed to be considering a career in music upon his completion of the Gymnasium in Horn. However, the death of his father, the village's doctor, in 1903 led him to pursue medicine instead, as his father's death caused the family considerable hardship that a career as a physician was more likely to reverse.[2]

He began his studies at the University of Vienna's medical school in 1907. During his time there he became a member of the Student Academic Fraternity of Germany, a student group with a strong German nationalist persuasion. As a student he had worked under Ferdinand Hochstetter, director of the university's anatomy institute. Hochstetter became his mentor and one of his strongest influences.[3] In 1912 he received his medical degree.[2]

For the next eight years he taught anatomy at various institutions in Austria. He served in the military as a physician for a year during World War I. In 1920 he returned to Vienna to work as one of Hochstetter's assistants, lecturing to first- and second-year students about the peripheral nervous and cardiovascular systems.[2]

Career and political activity

Back in Vienna he rose quickly in the academic ranks. In 1926 he earned the title of associate professor, with a promotion to full professor two years later. Five years after that, in 1933, he formally succeeded Hochstetter as the anatomical institute's director. At the ceremony installing him in that position, he acknowledged Hochstetter's tutelage by dropping to his knees in front of the older man and kissing him on the hand.[2]

Also in 1933, he joined the Nazi Party's foreign organization. The following year he became a member of the Sturmabteilung, better known as the SA, Storm Troopers or "brownshirts". In 1938 he was promoted again, becoming dean of the medical school. This occurred at about the same time as the Anschluss, Germany's annexation of Austria into the Third Reich.

In his new position, in a supportive political environment, Pernkopf put his Nazi beliefs into action. He required medical faculty to declare their ethnic lineage as either "Aryan" or "non-Aryan" and swear loyalty to Nazi leader Adolf Hitler. He forwarded a list of those who refused the latter to the university administration, who dismissed them from their jobs. This amounted to 77% of the faculty, including three Nobel laureates.[4] All of the Jewish faculty were removed this way,[3] making Pernkopf the first Austrian medical school dean to do so.[5]

Four days after becoming dean, he gave a speech to the medical faculty advocating Nazi racial hygiene theories and policies and urging his fellow physicians to implement them in their teaching and practice. They should "[promote] those whose heredity is more valuable and whose biological constitution due to heredity gives the promise of healthy offspring [and prevent] offspring to those who are racially inferior and of those who do not belong." More specifically, he said, the latter could be accomplished by "the exclusion of those who are racially inferior from the propagation of their offspring by means of sterilization and other means," language that has been seen as anticipating both the Nazi euthanasia programs and the Holocaust, the systematic extermination of European Jews and Romani. As he had begun his speech with "Heil Hitler!" and a Nazi salute, praising Hitler as "a son of Austria who had to leave Austria in order to bring it back into the family of German-speaking nations", he returned to that theme in his conclusion:

To him who is the proclaimer of National Socialist thought and the new way of looking at the world and in whom the legend of history has blossomed and has awakened and who has the heroic spirit within him, the greatest son of our homeland, we wish to give our gratitude and also to say that we doctors with our whole life and our whole soul gladly wish to serve him. So may our call express only what each of us feels from the bottom of his heart; Adolph Hitler, Sieg Heil!, Sieg Heil! Sieg Heil![3]

Atlas

At the time he was first hired as Hochstetter's assistant, he began putting together an informal dissection manual for students. He kept expanding it, and it became popular with the rest of the university instructors and the Austrian medical community. As he attained his full professorship he was offered a contract to expand it into a publishable book, and he eagerly accepted.[3] He was to deliver three volumes.[2]

Pernkopf began his atlas in 1933. He worked 18-hour days dissecting corpses, teaching classes and discharging his administrative responsibilities while a team of artists created the images that would eventually be in the atlas.[6] His days began at 5 a.m., when he left notes in shorthand for his wife to type. These became the descriptive text that accompanied the images.[2]

At the beginning four artists—Erich Lepier, Ludwig Schrott, Karl Endtresser and Franz Batke—worked with Pernkopf. Lepier, Pernkopf's first hire, had largely learned on his own after having to cut short his architectural studies at what is now Vienna University of Technology due to the death of his father, a circumstance similar to that which had shaped Pernkopf's career choice. The other three all had some degree of formal training.[3] Outside of these four, some other artists, mostly family members such as Schrott's father and Batke's wife, contributed some pictures during the atlas's early years.[2]

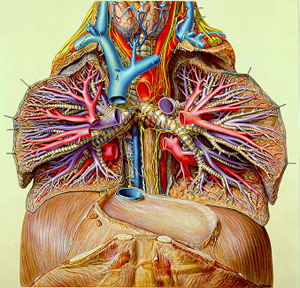

Pernkopf instructed them to paint the organs they saw in as much detail as possible, to make them look like living tissue in print. This was enabled by a special treatment of the paper used for watercolor images that allowed greater detail than that type of paint normally did. The only deviation from this high level of realism was the use of color, where Pernkopf instructed them to use brighter hues than those found in real cadavers so that a reader would better learn to recognize and distinguish key anatomical landmarks.[2]

Like Pernkopf, the four artists were also members of the Nazi Party and committed to its goals. They signaled this through the use of Nazi symbols in their work for the atlas. In his signature, Lepier frequently used the "r" at the end of his name as the basis for a swastika, and Endtrasser likewise used two Sig runes, the lightning-bolt insignia of the Schutzstaffel (SS), for the "ss" in his name. For illustrations he made in 1944, Batke similarly dated them by stylizing the two "4"'s as Sig Runes.[7]

The first volume of the atlas was published in 1937. It was large enough that it required two books, one devoted to anatomy in general and the other covering more specifically the chest and pectoral limbs. Four years later, in 1941, the second volume, likewise requiring two books, came out. It covered the abdomen, pelvis and pelvic limbs.[2]

That year the war intervened. With the exception of Lepier, ineligible for service because of his severe varicose veins, all the artists entered military service. Lepier nevertheless volunteered as an air raid warden, as did Batke when he returned home after being wounded and receiving the Iron Cross on the Eastern front. That duty took time away from their continued artistic work.[2]

Later life

In 1943, Pernkopf reached the pinnacle of the academic career ladder when he was named the University of Vienna's rector, its highest official. He continued to serve in those positions until World War II ended two years later, with the surrender of Germany, including Austria. His fortunes would change radically as a result.[2]

Two days after the surrender, he was dismissed from his post as head of the university's anatomical institute. Fearing that he might suffer legal or political repercussions for his previous Nazi party membership and prewar actions, he went on what he claimed was a vacation to Strobl in the state of Salzburg. However, he was arrested by American military authorities in August 1945, and by May 1946 he had been terminated from all his remaining positions with the university.[3]

He was held at the Allied prisoner of war (POW) camp in Glasenbach for three years. Although he was ultimately never charged with any crimes, he was required to do regular hard labor throughout his imprisonment. The experience left him drained and exhausted when he returned to Vienna after his release, hoping to continue his work on the atlas.[2]

His former facilities at the university were unavailable to him since the anatomical institute had been bombed during the war. Hans Hoff, a Jewish physician who had left the Vienna faculty in 1938, gave him two rooms at the school's neurological institute.[3] Pernkopf was reunited with his original artists, some of whom had also been held in POW camps, as well as some new ones, and resumed his earlier demanding schedule. They continued working in the small space Hoff gave them. There was some tension among them as the three who had served felt Lepier, with whom they had never been close personally to begin with, had had a much easier time of it during the war than they had, a bitterness aggravated by the Third Reich's defeat by the Allies. He worked by himself while Pernkopf resumed his prewar schedule despite the privations he had endured.[2]

They were joined by two new painters. Wilhelm Dietz, older than the others, contributed paintings of the neck and pharynx during his two years on the project. Elfie von Siber painted facial muscles. The third volume, covering the head and neck, was released in 1952.[2]

At the time of his death, Pernkopf was hard at work on the fourth volume. Two of his former colleagues, Alexander Pickler and Werner Platzer, completed it for its 1960 publication. A few years later, the publisher brought out a condensed two-volume set with all the color plates, removing most of Pernkopf's explanatory text (and, later, airbrushing out the Nazi symbols Lepier and the others added to their signatures). Since little translation was necessary, this was the version of the atlas which medical students and physicians elsewhere in the world came to know and revere.[3]

Controversial legacy and debate over continued use

In 1996 Pernkopf and his atlas came into the focus of a controversy in scientific ethics when Dr. Howard Israel, an oral surgeon at Columbia University, revealed that the subject bodies may have in some cases been those of executed political prisoners. Looking at older copies in the archives, Israel discovered many of the Nazi symbols in the artists' signatures, which had been removed from more widely circulated later versions. Since then physicians have discussed whether it is ethical to use the atlas as it resulted from Nazi medical research.[1][8]

With the help of other parties, Dr. Israel directed a request to the University of Vienna to investigate the issue. This resulted in the establishment of the Senatorial Project of the University of Vienna "Studies in Anatomical Science in Vienna from 1938 to 1945" [9] in 1997. The project confirmed that at least 1,377 bodies of executed persons were delivered to the University during the Nazi times and its usage cannot be excluded from at least 800 images of the atlas. As a result the atlas' publisher directed that an insert noting this possibility be mailed to all libraries holding the atlas, and stopped printing new copies.[10]

Some readers have wondered if the bodies shown in cutaway may have been Jewish inmates at concentration camps,[11] since they appear gaunt and have shaved heads or close-cropped haircuts.[3] Israel asked the Simon Wiesenthal Center if this might have been the case. Wiesenthal himself answered that it was unlikely, since during the Third Reich the Vienna Landsgericht, or district court, passed death sentences solely on "non-Jewish Austrian patriots, communists and other enemies of the Nazis."[2] Further, it has long been standard practice to shave the heads of cadavers prior to dissection.[3]

Scientists and bioethicists have debated whether it is acceptable to continue to use the atlas for instructional purposes in light of its possible provenance. Opponents have asserted that any use of the atlas makes the user complicit in Nazi crimes and that modern technology, such as the Visible Human Project, will make the atlas redundant if it has not done so already. Proponents have countered that the knowledge gained from the atlas can be ethically separated from its origins nor can it be in some cases easily replaced by modern technology or other atlases. "[Pernkopf's] atlas is still one of the very best in terms of accuracy, showing levels of detail concerning fascia and neurovascular structures that are of direct relevance for the actual dissection process," says Sabine Hildebrandt, a Michigan anatomy professor and German native who has researched him and other Nazi-era anatomists thoroughly.[12]

Further, they say, its paintings are artistic masterpieces regardless of the politics of the artists. Finally, forcing it out of circulation would be no less an act of censorship than that perpetrated by Hitler's regime when it publicly burned books shortly after assuming power.[13]

Some of the scientists who were involved in bringing the activities of Pernkopf and other Nazi-era anatomists to light advocate for the atlas' continued use. "[They] can remind us of suffering not only in the past but in the present, that we may be more compassionate physicians, more compassionate citizens of the world," says Garrett Riggs, a Florida neurologist and medical historian.[14] "[A] ban could not atone the great evil committed by human beings on other human beings," Hildebrandt argues. "Rather, it is up to a new human generation to glean good from this murky history by continuing to use Pernkopf's atlas in a rational, historically conscious manner."[12]

On the other hand, "There can be no doubt that Pernkopf, as head of the Anatomy Institute, was instrumental in the procurement of the bodies of the victims of Nazi terror for dissection, and ultimately, for the creation of his Atlas," argues Pieter Carstens, a professor of medical law at the University of South Africa. "In this sense he was an indirect perpetrator in the execution of the victims, but a direct perpetrator in the subsequent processing and pillaging of the bodies." Following the theories of bioethicist Charles A. Foster, he sees the anatomist's fundamental crime as a violation of his subjects' dignity.[15] He concludes:

How can something so beautiful at the same time be so utterly despicable? Herein lies the paradox of the Pernkopf Atlas, as a legacy of the Third Reich: the fact that Pernkopf and his illustrators, by embracing Nazi ideology and benefiting from the atrocities committed, created a Nazi anatomy atlas in which irreconcilable opposites were forcibly reconciled. Beautiful anatomical drawings were created, but this was only made possible by the unethical and unlawful procurement of the anatomical remains of murdered victims of an evil Nazi regime–thus beauty and evil were fused. This fusion not only perverts and diminishes the status and content of the Pernkopf Atlas, but also explains why it should be rejected.

[It] should be permitted to show its duplicitous face only rarely and then for very good reason in the teaching of history, medical ethics and medical law so that its lessons will be learned and its history never repeated.[16]

See also

References

- ^ a b Dittrick Medical History Center (2010). "The Pernkopf anatomical atlas controversy: issues of Nazi medicine and medical ethics". Case Western Reserve University. Retrieved 27 July 2010. [dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Williams, David J. (Spring 1988). "The History of Eduard Pernkopf's Topographische Anatomie des Menschen". Journal of Biocommunication. 15 (2): 2–12. PMID 3047110. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hubbard, Chris (October 2001). "Eduard Pernkopf's atlas of topographical and applied human anatomy: The continuing ethical controversy". The Anatomical Record. 265 (5): 207–211. doi:10.1002/ar.1157. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ Carstens, Pieter (2012). "Revisiting the Infamous Pernkopf Anatomy Atlas: Historical Lessons for Medical Law and Ethics" (PDF). Fundamina. 18 (2). Pretoria, South Africa: University of South Africa: 28. ISSN 1021-545X. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ Bazelon, Emily (6 November 2013). "The Nazi Anatomists". Slate. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ Pringle, Heather (2010). "The Dilemma of Pernkopf's Atlas". Science. 329 (5989): 274–275. doi:10.1126/science.329.5989.274-b. PMID 20647444.

- ^ Pieters, 30–31.

- ^ Wade, Nicholas (26 November 1996). "Doctors Question Use Of Nazi's Medical Atlas". The New York Times.

- ^ Malina, P; Spann, G (1999). "SENATORIAL PROJECT OF THE UNIVERSITY OF VIENNA, "STUDIES IN ANATOMICAL SCIENCE IN VIENNA FROM 1938 TO 1945"". Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift. 111 (18). Springer: 743–753. PMID 10546319.

- ^ Hildebrandt, Sabine (2006). "How the Pernkopf controversy facilitated a historical and ethical analysis of the anatomical sciences in Austria and Germany: A recommendation for the continued use of the Pernkopf atlas". Clinical Anatomy. 19 (2): 91. doi:10.1002/ca.20272.

- ^ "Case 2 The Dilemma of Tainted Data". Kennedy Institute of Ethics. Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- ^ a b Hildebrandt, 97.

- ^ Carstens, 11–12.

- ^ Riggs, Garrett (1998). "What should we do about Eduard Pernkopf's atlas?". Academic Medicine. 73 (4): 380–386. doi:10.1097/00001888-199804000-00010. PMID 9580714.

- ^ Carstens, 41–45.

- ^ Carstens, 48.

Further reading

- Holubar, Karl, "The Pernkopf Story: The Austrian Perspective of 1998, 60 Years after It All Began", Perspectives in Biology and Medicine - Volume 43, Number 3, Spring 2000, pp. 382–388, doi:10.1353/pbm.2000.0020