Ext functor

In mathematics, the Ext functors of homological algebra are derived functors of Hom functors. They were first used in algebraic topology, but are common in many areas of mathematics. The name "Ext" comes from group theory, as the Ext functor is used in group cohomology to classify abelian group extensions.[1]

Definition and computation

Let R be a ring and let ModR be the category of modules over R. Let B be in ModR and set T(B) = HomR(A,B), for fixed A in ModR. This is a left exact functor and thus has right derived functors RnT. The Ext functor is defined by

This can be calculated by taking any injective resolution

and computing

Then (RnT)(B) is the homology of this complex. Note that HomR(A,B) is excluded from the complex.

An alternative definition is given using the functor G(A)=HomR(A,B). For a fixed module B, this is a contravariant left exact functor, and thus we also have right derived functors RnG, and can define

This can be calculated by choosing any projective resolution

and proceeding dually by computing

Then (RnG)(A) is the homology of this complex. Again note that HomR(A,B) is excluded.

These two constructions turn out to yield isomorphic results, and so both may be used to calculate the Ext functor.

Properties of Ext

The Ext functor exhibits some convenient properties, useful in computations.[2]

- Exti

R(A, B) = 0 for i > 0 if either B is injective or A projective. - The converses also hold:

- If Ext1

R(A, B) = 0 for all A, then Exti

R(A, B) = 0 for all A, and B is injective. - If Ext1

R(A, B) = 0 for all B, then Exti

R(A, B) = 0 for all B, and A is projective.

- If Ext1

- for all n ≥ 2 abelian groups A and B.

- for all abelian B.[3]

- Let A be a finitely generated module over a commutative noetherian ring R. Then for every multiplicative set S, all modules B, and all n,

- If R is commutative noetherian and A is a finitely generated R-module, then the following are equivalent for all modules B and all n:

- For every prime ideal of R, .

- For every maximal ideal of R, .

Ext and extensions

Equivalence of extensions

Ext functors derive their name from the relationship to extensions of modules. Given R-modules A and B, an extension of A by B is a short exact sequence of R-modules

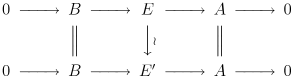

Two extensions

are said to be equivalent (as extensions of A by B) if there is a commutative diagram

Note that the Five Lemma implies that the middle arrow is an isomorphism. An extension of A by B is called split if it is equivalent to the trivial extension

There is a bijective correspondence between equivalence classes of extensions

of A by B and elements of

The Baer sum of extensions

Given two extensions

we can construct the Baer sum, by forming the pullback over ,

We form the quotient

- ,

that is, we mod out by the relation . The extension

where the first arrow is and the second thus formed is called the Baer sum of the extensions E and E′.

Up to equivalence of extensions, the Baer sum is commutative and has the trivial extension as identity element. The extension 0 → B → E → A → 0 has for its inverse the same extension with exactly one of the central arrows replaced with its negative e.g. the morphism g is replaced by -g.

The set of extensions up to equivalence is an abelian group that is a realization of the functor Ext1

R(A, B)

Construction of Ext in abelian categories

The above identification enables us to define Ext1

Ab(A, B) even for abelian categories Ab without reference to projectives and injectives (even if the category has no projectives or injectives). We simply take Ext1

Ab(A, B) to be the set of equivalence classes of extensions of A by B, forming an abelian group under the Baer sum. Similarly, we can define higher Ext groups Extn

Ab(A, B) as equivalence classes of n-extensions, which are exact sequences

under the equivalence relation generated by the relation that identifies two extensions

if there are maps Xm → X′m for all m in {1, 2, ..., n} so that every resulting square commutes, i.e. if there is a chain map .

The Baer sum of the two n-extensions above is formed by letting be the pullback of and over A, and be the pushout of and under B; see Weibel, §3.4 (but remark there are some errata). Then we define the Baer sum of the extensions to be

Ring structure and module structure on specific Exts

One more very useful way to view the Ext functor is this: when an element of Extn

R(A, B) = 0 is considered as an equivalence class of maps for a projective resolution of A ; so, then we can pick a long exact sequence ending with B and lift the map f using the projectivity of the modules Pm to a chain map of degree −n. It turns out that homotopy classes of such chain maps correspond precisely to the equivalence classes in the definition of Ext above.

Under sufficiently nice circumstances, such as when the ring R is a group ring over a field k, or an augmented k-algebra, we can impose a ring structure on The multiplication has quite a few equivalent interpretations, corresponding to different interpretations of the elements of

One interpretation is in terms of these homotopy classes of chain maps. Then the product of two elements is represented by the composition of the corresponding representatives. We can choose a single resolution of k, and do all the calculations inside which is a differential graded algebra, with cohomology precisely ExtR(k, k).

The Ext groups can also be interpreted in terms of exact sequences; this has the advantage that it does not rely on the existence of projective or injective modules. Then we take the viewpoint above that an element of Extn

R(A, B) is a class, under a certain equivalence relation, of exact sequences of length n + 2 starting with B and ending with A. This can then be spliced with an element in Extm

R(C, A), by replacing

with:

where the map is the composition of X1 → A and A → Yn. This product is called the Yoneda splice.

These viewpoints turn out to be equivalent whenever both make sense.

Using similar interpretations, we find that is a module over again for sufficiently nice situations.

Interesting examples

If is the integral group ring for a group G, then is the group cohomology H*(G,M) with coefficients in M.

If A is a k-algebra, then is the Hochschild cohomology HH*(A,M) with coefficients in the A-bimodule M.

If R is chosen to be the universal enveloping algebra for a Lie algebra over a commutative ring k, then is the Lie algebra cohomology with coefficients in the module M.

See also

- Tor functor

- The Grothendieck group is a construction centered on extensions

- The universal coefficient theorem for cohomology is one notable use of the Ext functor

- Grothendieck duality

- Yoneda product

References

- ^ "nLab:Ext". nLab. Retrieved 2015-07-23.

It derives its name from the fact that the derived hom between abelian groups classifies abelian group extensions of A by K. (This is a special case of the general classification of principal ∞-bundles/∞-group extensions by general cohomology/group cohomology.)

- ^ Weibel, Charles A. (1997). An introduction to homological algebra (Repr. ed.). [Cambridge]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521559874.

- ^ This along with (which follows from the projectivity of ) can be used to compute for any finitely generated abelian group A.

- Gelfand, Sergei I.; Manin, Yuri Ivanovich (1999), Homological algebra, Berlin: Springer, ISBN 978-3-540-65378-3

- Weibel, Charles A. (1994). An introduction to homological algebra. Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics. Vol. 38. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-55987-4. MR 1269324. OCLC 36131259.

![{\displaystyle b\mapsto [(f(b),0)]=[(0,f'(b))]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ee75b87481bf9de19754e30ff4b98f9e3a93c53f)

![{\displaystyle \mathbb {Z} [G]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f40260c366fc309a5872899d2ea34cf094855857)

![{\displaystyle \operatorname {Ext} _{\mathbb {Z} [G]}^{*}(\mathbb {Z} ,M)}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/310b83bea399442efbe7e0e85d165767875a10e5)