Exterior angle theorem

The exterior angle theorem is Proposition 1.16 in Euclid's Elements, which states that the measure of an exterior angle of a triangle is greater than either of the measures of the remote interior angles. This is a fundamental result in absolute geometry because its proof does not depend upon the parallel postulate.

In several high school treatments of geometry, the term "exterior angle theorem" has been applied to a different result,[1] namely the portion of Proposition 1.32 which states that the measure of an exterior angle of a triangle is equal to the sum of the measures of the remote interior angles. This result, which depends upon Euclid's parallel postulate will be referred to as the "High school exterior angle theorem" (HSEAT) to distinguish it from Euclid's exterior angle theorem.

Some authors refer to the "High school exterior angle theorem" as the strong form of the exterior angle theorem and "Euclid's exterior angle theorem" as the weak form.[2]

Exterior angles

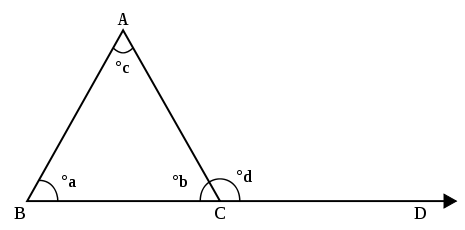

A triangle has three corners, called vertices. The sides of a triangle (line segments) that come together at a vertex form two angles (four angles if you consider the sides of the triangle to be lines instead of line segments).[3] Only one of these angles contains the third side of the triangle in its interior, and this angle is called an interior angle of the triangle.[4] In the picture below, the angles ∠ABC, ∠BCA and ∠CAB are the three interior angles of the triangle. An exterior angle is formed by extending one of the sides of the triangle; the angle between the extended side and the other side is the exterior angle. In the picture, angle ∠ACD is an exterior angle.

Euclid's exterior angle theorem

The proof of Proposition 1.16 given by Euclid is often cited as one place where Euclid gives a flawed proof.[5][6][7]

Euclid proves the exterior angle theorem by:

- construct the midpoint E of segment AC,

- draw the ray BE,

- construct the point F on ray BE so that E is (also) the midpoint of B and F,

- draw the segment FC.

By congruent triangles we can conclude that ∠ BAC = ∠ ECF and ∠ ECF is smaller than ∠ ECD , ∠ ECD = ∠ ACD therefore ∠ BAC is smaller than ∠ ACD and the same can be done for the angle ∠ CBA by bisecting BC.

The flaw lies in the assumption that a point (F, above) lies "inside" angle (∠ ACD). No reason is given for this assertion, but the accompanying diagram makes it look like a true statement. When a complete set of axioms for Euclidean geometry is used (see Foundations of geometry) this assertion of Euclid can be proved.[8]

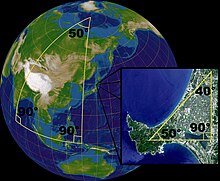

Invalid in Spherical geometry

The exterior angle theorem is not valid in spherical geometry nor in the related elliptical geometry. Consider a spherical triangle one of whose vertices is the North Pole and the other two lie on the equator. The sides of the triangle emanating from the North Pole (great circles of the sphere) both meet the equator at right angles, so this triangle has an exterior angle that is equal to a remote interior angle. The other interior angle (at the North Pole) can be made larger than 90°, further emphasizing the failure of this statement. However, since the Euclid's exterior angle theorem is a theorem in absolute geometry it is automatically valid in hyperbolic geometry.

High school exterior angle theorem

The high school exterior angle theorem (HSEAT) says that the size of an exterior angle at a vertex of a triangle equals the sum of the sizes of the interior angles at the other two vertices of the triangle (remote interior angles). So, in the picture, the size of angle ACD equals the size of angle ABC plus the size of angle CAB.

The HSEAT is logically equivalent to the Euclidean statement that the sum of angles of a triangle is 180°. If it is known that the sum of the measures of the angles in a triangle is 180°, then the HSEAT is proved as follows:

On the other hand, if the HSEAT is taken as a true statement then:

Proving that the sum of the measures of the angles of a triangle is 180°.

The Euclidean proof of the HSEAT (and simultaneously the result on the sum of the angles of a triangle) starts by constructing the line parallel to side AB passing through point C and then using the properties of corresponding angles and alternate interior angles of parallel lines to get the conclusion as in the illustration.[9]

The HSEAT can be extremely useful when trying to calculate the measures of unknown angles in a triangle.

Notes

- ^ Henderson & Taimiņa 2005, p. 110

- ^ Wylie, Jr. 1964, p. 101 & p. 106

- ^ One line segment is considered the initial side and the other the terminal side. The angle is formed by going counterclockwise from the initial side to the terminal side. The choice of which line segment is the initial side is arbitrary, so there are two possibilities for the angle determined by the line segments.

- ^ This way of defining interior angles does not presuppose that the sum of the angles of a triangle is 180 degrees.

- ^ Faber 1983, p. 113

- ^ Greenberg 1974, p. 99

- ^ Venema 2006, p. 10

- ^ Greenberg 1974, p. 99

- ^ Heath 1956, Vol. 1, p. 316

References

- Faber, Richard L. (1983), Foundations of Euclidean and Non-Euclidean Geometry, New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc., ISBN 0-8247-1748-1

- Greenberg, Marvin Jay (1974), Euclidean and Non-Euclidean Geometries/Development and History, San Francisco: W.H. Freeman, ISBN 0-7167-0454-4

- Heath, Thomas L. (1956). The Thirteen Books of Euclid's Elements (2nd ed. [Facsimile. Original publication: Cambridge University Press, 1925] ed.). New York: Dover Publications.

- (3 vols.): ISBN 0-486-60088-2 (vol. 1), ISBN 0-486-60089-0 (vol. 2), ISBN 0-486-60090-4 (vol. 3).

- Henderson, David W.; Taimiņa, Daina (2005), Experiencing Geometry/Euclidean and Non-Euclidean with History (3rd ed.), Pearson/Prentice-Hall, ISBN 0-13-143748-8

- Venema, Gerard A. (2006), Foundations of Geometry, Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, ISBN 0-13-143700-3

- Wylie, Jr., C.R. (1964), Foundations of Geometry, New York: McGraw-Hill

HSEAT references

- Geometry Textbook - Standard IX, Maharashtra State Board of Secondary and Higher Secondary Education, Pune - 411 005, India.

- Geometry Common Core, 'Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, ©2010, pages 171-173 | United States.

- Wheater, Carolyn C. (2007), Homework Helpers: Geometry, Franklin Lakes, NJ: Career Press, pp. 88–90, ISBN 978-1-56414-936-7.