Feriköy Protestant Cemetery

| Feriköy Protestant Cemetery | |

|---|---|

The main gate of Istanbul Protestant Cemetery | |

| |

| Details | |

| Established | 1859 |

| Location | |

| Country | Turkey |

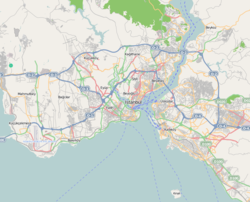

| Coordinates | 41°03′14″N 28°59′02″E / 41.053889°N 28.983889°E |

| Type | Protestant Cemetery |

| Style | 19th Century European |

Feriköy Protestant Cemetery (Turkish: Feriköy Protestan Mezarlığı) officially called Evangelicorum Commune Coemeterium is a Christian cemetery in Istanbul, Turkey. As its name indicates, it is the final resting place of Protestants residing in Istanbul. The cemetery is in the Feriköy neighborhood in the Şişli district of Istanbul, nearly 3 km (1.9 mi) north of Taksim Square.

In 1857 the Ottoman government donated the land for this cemetery to the leading Protestant powers of that time, the United Kingdom, Prussia, the United States, the Netherlands, Sweden, Norway, Denmark and the Hanseatic League together with the Grand Duchy of Oldenburg.[1] Since then, roughly 5,000 individuals have been interred here.

In Istanbul, all members of the Reformed Churches as well as Lutherans and Anglicans belong to the Protestant Cemetery in Feriköy, and burial plots are distributed by the Consulates General of Germany, the United Kingdom, the United States, the Netherlands, Sweden, Hungary and Switzerland. They exchange the task of management biennially.[2]

The cemetery contains examples of many different styles of memorial from the 17th century to the present day. The stones propped up along the walls are some of the last links to the old Frankish burial ground in the Grand Champs des Morts, Pera's 'Great Field of the Dead', which was lost to urban development during the 19th century.

History

[edit]Between 1840 and 1910, the area of Istanbul stretching northward from Taksim to Şişli was transformed from open countryside to densely inhabited residential settlement. Early 19th century maps of Istanbul show much of the area in this direction taken up by the non-Muslim burial grounds of the Grand Champs des Morts, with the Frankish section directly in the path of the main route of expansion. The urban development in the Ottoman capital, influenced by Western models, led to the closure of the Grand Champs des Morts – Istanbul's `City of the Dead', a world-renowned necropolis, which had provided inspiration, as well as an ideal, for the cemetery reformers of Europe.

Already by 1842, this burial ground was being whittled down, as a contemporary account by Reverend William Goodell attests. One of the founders of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions to the Armenians at Istanbul, Goodell had lost his nine-year-old son, Constantine Washington, to typhoid fever in 1841 and buried him in the Frankish section of the Grand Champs des Morts.

From the memoirs of Reverend William Goodell on February 18, 1842 : On account of the encroachments on the Frank burying ground, I had to remove the body of our beloved boy. The grave had been dug deep, and the coffin was scarcely damp. Every thing was sweet and still. The new grave which we have prepared a few rods distant was also deep and dry; and there we laid the body, to rest in its quiet bed till the resurrection morning. Beloved child, farewell![3]

However, little Constantine's tranquility lasted far less than expected, disturbed again by a flurry of construction in the early 1860s. In July 1863, the remains of more than a dozen Americans, including those of Constantine Washington Goodell, were exhumed from the old Frankish burial ground in the Grand Champs des Morts. They were transferred, along with their grave markers, to a new Protestant cemetery in Feriköy – created by order of Sultan Abdülmecid I in the 1850s – for re-interment.

The land occupied by the former burial ground was turned into a public park (in a modern Western sense), a project finally completed six years later with the opening of Taksim Garden in 1869.[citation needed]

The first body was interred at the new site in November 1858, but the cemetery did not official open until early in 1859. Although the burial ground was created primarily for foreign nationals, a separate section in the southwest corner is reserved for Armenian Protestants.[4]

There is one Commonwealth war grave, of an officer of the British Army Intelligence Corps, who died during World War II in 1945.[5]

The Armenian Protestant section

[edit]The burial plot reserved for Armenian Protestants is separated by a wall from the main cemetery where foreign Protestants are laid to rest, since Armenians were regarded as "Ottoman subjects". In this small section, there are also some graves belonging to Greeks, Arabs, Assyrians and Turkish Protestants most of whom are former Muslims that converted to Protestantism with epitaphs written in five different languages.

Selected notable burials

[edit]A few of the notables buried here are:

- Betty Carp (1895–1974), American embassy official and intelligence agent.

- Ernest Mamboury (1878–1953), Swiss scholar renowned for his works on the historic structures in Turkish cities, particularly on Byzantine art and architecture in Istanbul.

- Hilary Sumner-Boyd (1910–1976) and John Freely (1926–2017), co-authors of Strolling Through Istanbul, a seminal guidebook to the city.

- Josephine Powell (1919–2007), explorer of Turkey and collector of carpets ad kilims

- Paul Lange (1857–1919), Last Court Musician of the Ottoman Court, Important orchestra and choir conductor in Istanbul in the years 1880–1919.

- William Nosworthy Churchill (1796–1846), British journalist who became editor of the Ceride-i Havadis newspaper in the Ottoman Empire.

Gallery

[edit]-

Memorial to Hungarian freedom fighters of 1848–1849 at Protestant Cemetery in Istanbul

-

Istanbul Feriköy Protestant cemetery

-

The funerary chapel

-

Old graves and tombstones

-

Feriköy Protestant Cemetery Chapel

-

Feriköy Protestant Cemetery Old gravestones

-

Feriköy Protestant Cemetery Old gravestone

-

Feriköy Protestant Cemetery Old gravestone

-

Feriköy Protestant Cemetery Old gravestone

See also

[edit]External links and references

[edit]- ^ "NLA OL Best. 130 Best. 131 Nr. 604 – Finanzieller anteiliger Bei... – Arcinsys detail page". www.arcinsys.niedersachsen.de. Retrieved 2019-12-18.

- ^ "note71". www.levantineheritage.com.

- ^ Prime, Memoirs of Rev. William Goodell, D.D. (Robert Carter and Brothers, 1876)

- ^ Historian Brian Johnson who works with the American Board in Istanbul is currently [2001–03] engaged in compiling an accurate a list as possible of the names and nationalities of those buried at Ferikoy, from its opening in the 19th century to the present

- ^ [1] CWGC Casualty record.

- The Fountain Magazine | Istanbul's Vanished City of the Dead: The Grand Champs des Morts

- Views of the Feriköy Protestant cemetery

- 50 pictures of the graveyard

- Visitor Guide – Ferikoy Cemetery

- Booklet – Ferikoy Cemetery

- Connections – Ferikoy Cemetery

- Istanbul's Christian and Jewish Cemeteries from 1453 Until Today | History of Istanbul