Flat bone

| Flat bone | |

|---|---|

Anatomy of a flat bone (Frontal bone) | |

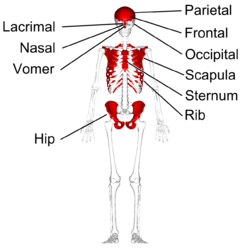

Flat bones in human skeleton. (shown in red) | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | os planum |

| TA98 | A02.0.00.013 |

| TA2 | 371 |

| FMA | 7476 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

Flat bones are bones whose principal function is either extensive protection or the provision of broad surfaces for muscular attachment. These bones are expanded into broad, flat plates,[1] as in the cranium (skull), the ilium (pelvis), sternum and the rib cage. The flat bones are: the occipital, parietal, frontal, nasal, lacrimal, vomer, hip bone (coxal bone), sternum, ribs, and scapulae.[1] In the cranial bones, the layers of compact tissue are familiarly known as the tables of the skull; the outer one is thick and tough; the inner is thin, dense, and brittle, and hence is termed the vitreous (glass-like) table.[1]

These bones are composed of two thin layers of compact bone enclosing between them a variable quantity of cancellous bone,[1] which is the location of red bone marrow. In an adult, most red blood cells are formed in flat bones. The intervening cancellous tissue is called the diploë, and this, in the nasal region of the skull, becomes absorbed so as to leave spaces filled with air–the paranasal sinuses between the two tables.[1]

Ossification in flat bones

Ossification is started by the formation of layers of undifferentiated connective tissue that hold the area where the flat bone is to come. On a baby, those spots are known as fontanelles. The fontanelles contain connective tissue stem cells, which form into osteoblasts, which secrete calcium phosphate into a matrix of canals. They form a ring in between the membranes, and begin to expand outwards. As they expand they make a bony matrix.

This hardened matrix forms the body of the bone. Since flat bones are usually thinner than the long bones, they only have red bone marrow, rather than both red and yellow bone marrow (yellow bone marrow being made up of mostly fat). The bone marrow fills the space in the ring of osteoblasts, and eventually fills the bony matrix.

After the bone is completely ossified, the osteoblasts retract their calcium phosphate secreting tendrils, leaving tiny canals in the bony matrix, known as canaliculi. These canaliculi provide the nutrients needed for the newly transformed osteoblasts, which are now called osteocytes. These cells are responsible for the general maintenance of the bone.

A third type of bone cell found in flat bones is called an osteoclast, which destroys the bone using enzymes. There are three reasons that osteoclasts are normally used: the first is for the reparation of bones after a break. They destroy sections of bone that protrude or make reformation difficult. They are also used to obtain necessary calcium from the bones. When a person's blood calcium is low, the osteoclasts take calcium from the bone and put it into the blood for necessary things such as nerve and muscle action. The last reason that osteoclasts are used is for growing. As the bone grows, its shape changes. The osteoclasts dissolve the part of the bone that must change.[2]

Additional images

-

Flat bones in human skeleton. (shown in red)

-

Flat bones in human skull. (shown in red)

-

Classification of bones by shape.

References

![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 79 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 79 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2010) |