Foldamer

In chemistry, a foldamer is a discrete chain molecule or oligomer that folds into a conformationally ordered state in solution. They are artificial molecules that mimic the ability of proteins, nucleic acids, and polysaccharides to fold into well-defined conformations, such as helices and β-sheets. The structure of a foldamer is stabilized by noncovalent interactions between nonadjacent monomers.[2][3] Foldamers are studied with the main goal of designing large molecules with predictable structures. The study of foldamers is related to the themes of molecular self-assembly, molecular recognition, and host-guest chemistry.

Design

Foldamers can vary in size, but they are defined by the presence of noncovalent, nonadjacent interactions. This definition excludes molecules like poly(isocyanates) (commonly known as (polyurethane)) and poly(prolines) as they fold into helicies reliably due to adjacent covalent interactions.,[4][5] Foldamers have a dynamic folding reaction [unfolded → folded], in which large macroscopic folding is caused by solvophobic effects (hydrophobic collapse), while the final energy state of the folded foldamer is due to the noncovalent interactions. These interactions work cooperatively to form the most stable tertiary structure, as the completely folded and unfolded states are more stable than any partially folded state.[6]

Prediction of folding

The structure of a foldamer can often be predicted from its primary sequence. This process involves dynamic simulations of the folding equilibria at the atomic level under various conditions. This type of analysis may be applied to small proteins as well, however computational technology is unable to simulate all but the shortest of sequences.[7]

The folding pathway of a foldamer can be determined by measuring the variation from the experimentally determined favored structure under different thermodynamic and kinetic conditions. The change in structure is measured by calculating the root mean square deviation from the backbone atomal position of the favored structure. The structure of the foldamer under different conditions can be determined computationally and then verified experimentally. Changes in the temperature, solvent viscosity, pressure, pH, and salt concentration can all yield valuable information about the structure of the foldamer. Measuring the kinetics of folding as well as folding equilibria allow one to observe the effects of these different conditions on the foldamer structure.[7]

Solvent often influences folding. For example, a folding pathway involving hydrophobic collapse would fold differently in a nonpolar solvent. This difference is due to the fact that different solvents stabilize different intermediates of the folding pathway as well as different final foldamer structures based on intermolecular noncovalent interactions.[7]

Noncovalent interactions

Noncovalent intermolecular interactions, albeit individually small, their summation alters chemical reactions in major ways. Listed below are common intermolecular forces that chemists have used to design foldamers.

- Hydrogen bonding (especially with peptide bonds)

- Pi stacking

- Solvophobic effects, which lead to hydrophobic collapse

- Van der Waals forces

- Electrostatic attraction

Common designs

Foldamers are classified into three different categories: peptidomimetic foldamers, nucleotidomimetic foldamers, and abiotic foldamers. Peptidomimetic foldamers are synthetic molecules that mimic the structure of proteins, while nucleotidomimetic foldamers are based on the interactions in nucleic acids. Abiotic foldamers are stabilized by aromatic and charge-transfer interactions which are not generally found in nature.[2] The three designs described below deviate from Hill's[4] strict definition of a foldamer, which excludes helical foldamers.

Peptidomimetic

Peptidomimetic foldamers often break the previously mentioned definition of foldamers as they often adopt helical structures. They represent a major landmark of foldamer research due to their design and capabilities.[8][9] The largest groups of peptidomimetic consist of β – peptides, γ – peptides and δ – peptides, and the possible monomeric combinations.[9] The amino acids of these peptides only differ by one (β), two (γ) or three (δ) methylene carbons, yet the structural changes were profound. These peptide sequences are highly studied as sequence control leads to reliable folding prediction. Additionally, with multiple methylene carbons between the carboxyl and amino termini of the flanking peptide bonds, Varying R group side chains can be designed. One example of the novelty of β-peptides can be seen in the findings of Reiser and coworkers.[10] Using a heteroligopeptide consisting of α-amino acids and cis-β-aminocyclopropanecarboxulic acids (cis-β-ACCs) they found the formation of helical sequences in oligomers as short as seven residues and defined conformation in five residues; a quality unique to peptides containing cyclic β-amino acids.[11][12]

Nucleotidomimetic

Nucleotidomimetics do not generally qualify as foldamers. Most are designed to mimic single DNA bases, nucleosides, or nucleotides in order to nonspecifically target DNA.[13][14][15] These have several different medicinal uses including anti-cancer, anti-viral, and anti-fungal applications.

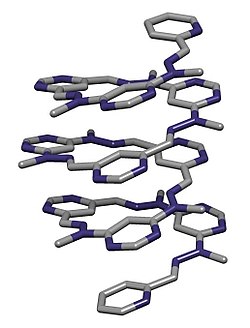

Abiotic

Abiotic foldamers are again organic molecules designed to exhibit dynamic folding. They exploit one or a few known key intermolecular interactions, as optimized by their design. One example is oligopyrroles that organize upon binding anions like chloride through hydrogen bonding (see figure). Folding is induced in the presence of an anion: the polypyrrole groups have little conformational restriction otherwise.[16][17]

Other examples

- m-Phenylene ethynylene oligomers are driven to fold into a helical conformation by solvophobic forces and aromatic stacking interactions.

- β-peptides are composed of amino acids containing an additional CH

2 unit between the amine and carboxylic acid. They are more stable to enzymatic degradation and have been demonstrated to have antimicrobial activity. - Peptoids are N-substituted polyglycines that utilize steric interactions to fold into polyproline type-I-like helical structures.[18]

- Aedamers that fold in aqueous solutions driven by hydrophobic and aromatic stacking interactions.

- Aromatic Oligomide Foldamers These examples are some of the largest and best structurally characterized Foldamers.[19]

- arylamide foldamers,[20] eg Brilacidin

References

- ^ Lehn, Jean-Marie; et al. (2003). "Helicity-Encoded Molecular Strands: Efficient Access by the Hydrazone Route and Structural Features". Helv. Chim. Acta. 86: 1598–1624. doi:10.1002/hlca.200390137.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last2=(help) - ^ a b Foldamers: Structure, Properties, and Applications" Stefan Hecht, Ivan Huc Eds. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2007. ISBN 9783527315635

- ^ Hill DJ, Mio MJ, Prince RB, Hughes TS, Moore JS (2001). "A field guide to foldamers". Chem. Rev. 101 (12): 3893–4012. doi:10.1021/cr990120t. PMID 11740924.

- ^ a b Hill, David; et al. (2001). "A Field Guide to Foldamers". Chem. Rev. 101: 3893–4011. doi:10.1021/cr990120t. PMID 11740924.

- ^ Green, M. M.;; Park, J.; Sato, T.; Teramoto, A.; Lifson, S.; Selinger, R.L.B.; Selinger, J.V. (1999). "The Macromolecular Route to Chiral Amplification". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 38: 3138–3154. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19991102)38:21<3138::AID-ANIE3138>3.0.CO;2-C.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gellman, S.H. (1998). "Foldamers: A Manifesto". Acc. Chem. Res. 31: 173–180. doi:10.1021/ar960298r.

- ^ a b c van Gunsteren, Wilfred F. (2007). Foldamers: Structure, Properties, and Applications; Simulation of Folding Equilibria. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. pp. 173–192. doi:10.1002/9783527611478.ch6.

- ^ Anslyn and Dougherty, Modern Physical Organic Chemistry, University Science Books, 2006, ISBN 978-1-891389-31-3

- ^ a b Martinek, T.A.; Fulop, F. (2012). "Peptidic foldamers: ramping up diversity". Chem. Soc. Rev. 41: 687–702. doi:10.1039/C1CS15097A.

- ^ De Pol, S.; Zorn, C.; Klein, C.D.; Zerbe, O.; Reiser, O. (2004). "Surprisingly Stable Helical Conformations in alpha/beta-Peptides by Incorporation of cis-beta-Aminocyclopropate Carboxylic Acids". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43: 511–514. doi:10.1002/anie.200352267.

- ^ Seebach, D.; Beck, A.K.; Bierbaum, D. J.; Chem. Biodiv., 2004, 1, 1111-1239.

- ^ Seebach, D.; Beck, A.K.; Bierbaum, D.J. (2004). "Chemical and Biological Investigations of B-Oligoarginines". Chem. Biodiv. 1: 1111–1239. doi:10.1002/cbdv.200490014.

- ^ Longley, DB; Harkin DP; Johnston PG (May 2003). "5-fluorouracil: mechanisms of action and clinical strategies". Nat. Rev. Cancer. 3 (5): 330–338. doi:10.1038/nrc1074. PMID 12724731.

- ^ Secrist, John (2005). "Nucleosides as anticancer agents: from concept to the clinic". Nucleic Acids Symposium Series. 49: 15–16. doi:10.1093/nass/49.1.15.

- ^ Rapaport, E.; Fontaine J (1989). "Anticancer activities of adenine nucleotides in mice are mediated through expansion of erythrocyte ATP pools". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 86: 1662–1666. Bibcode:1989PNAS...86.1662R. doi:10.1073/pnas.86.5.1662. PMC 286759.

- ^ Sessler, J.L.; Cyr, M.; Lynch, V. (1990). "Synthetic and structural studies of sapphyrin, a 22-.pi.-electron pentapyrrolic "expanded porphyrin"". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112: 2810. doi:10.1021/ja00163a059.

- ^ Juwarker, H.; Jeong, K-S. (2010). "Anion-controlled foldamers". Chem. Soc. Rev. 39: 3664–3674. doi:10.1039/b926162c.

- ^ Angelici, G.; Bhattacharjee, N.; Roy, O.; Faure, S.; Didierjean, C.; Jouffret, L.; Jolibois, F.; Perrin, L.; Taillefumier, C. (2016). "Weak backbone CH⋯O=C and side chain tBu⋯tBu London interactions help promote helix folding of achiral NtBu peptoids". Chemical Communications. 52 (24): 4573–4576. doi:10.1039/C6CC00375C.

- ^ Delsuc, Nicolas; Massip, Stéphane; Léger, Jean-Michel; Kauffmann, Brice; Huc, Ivan (9 March 2011). "Relative Helix−Helix Conformations in Branched Aromatic Oligoamide Foldamers". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 133 (9): 3165–3172. doi:10.1021/ja110677a.

- ^ De novo design and in vivo activity of conformationally restrained antimicrobial arylamide foldamers. Choi. 2009

Further reading

- Ivan Huc; Stefan Hecht (2007). Foldamers: Structure, Properties, and Applications. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. ISBN 3-527-31563-2.

- Goodman CM, Choi S, Shandler S, DeGrado WF (2007). "Foldamers as versatile frameworks for the design and evolution of function". Nat. Chem. Biol. 3 (5): 252–62. doi:10.1038/nchembio876. PMC 3810020. PMID 17438550.

Reviews

- ^ Gellman, S.H. (1998). "Foldamers: a manifesto" (PDF). Acc. Chem. Res. 31 (4): 173–180. doi:10.1021/ar960298r. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-05-13.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Zhang DW, Zhao X, Hou JL, Li ZT (2012). "Aromatic Amide Foldamers: Structures, Properties, and Functions". Chem. Rev. 112 (10): 5271–5316. doi:10.1021/cr300116k. PMID 22871167.

- ^ Juwarker, H.; Jeong, K-S. (2010). "Anion-controlled foldamers". Chem. Soc. Rev. 39: 3664–3674. doi:10.1039/b926162c.