French emigration (1789–1815)

French emigration from the years 1789 to 1815 refers to the mass movement of citizens from France to neighboring countries, in reaction to the instability and upheaval caused by the French Revolution and the succeeding Napoleonic rule. Although initiated in 1789 as a peaceful effort led by the Bourgeoisie to increase political equality for the Third Estate (the unprivileged majority of the French people), the Revolution soon turned into a violent, popular movement. To escape political tensions and, mainly during the Reign of Terror, to save their lives, a number of individuals emigrated from France and settled in the neighboring countries (chiefly Great Britain, Austria, and Prussia or other German states), though a few also went to the Americas.

Revolution begins

[edit]When the Estates General convened in May 1789 and aired out their political grievances, many members of each estate found themselves in agreement with the idea that the bulk of France, the Third Estate, was carrying the tax burden without equitable political representation. They even took an oath, the Tennis Court Oath, swearing to pursue their political goals and committing to drafting a constitution which codified equality. Soon, the ideologies of fair and equal treatment by the government and liberation from the old regime diffused throughout France.

The first émigrés

[edit]While Abbé Sièyes and several other men of the first and second estates supported the Third Estate's desire for equality, several members of the clergy and nobility were averse to it. Under the old regime, they were accustomed with a certain quality of living and with the right to pass this life to their children. The Revolution was looking to remove all privilege in an effort to make everyone politically equal, so the first émigrés, or emigrants, were proponents of the old order and chose to leave France although emigration abroad was not prohibited.[1]

The summer of 1789 saw the first voluntary émigrés. Many of these émigrés were members of the nobility who migrated out of fear sparked by the Storming of the Bastille in July 1789.[2] Notable émigrés include Madames Adélaïde and Victoire, aunts of King Louis XVI, who on 19 February 1791 started their journey to Rome to live nearer to the Pope. However, their journey was stopped by and largely debated by the National Assembly who feared that their emigration implied that King Louis and his family would soon follow suit. While this fear eventually resulted in the Day of Daggers and later the King's attempt to escape Paris, the Madames were permitted to continue their journey after statesman Jacques-François de Menou joking about the Assembly's preoccupation with the actions of "two old women".[3]

Upon settling in neighboring countries such as Great Britain, they were able to assimilate well and maintained a certain level of comfort in their new lifestyles. This was a significant emigration; it marked the presence of many royalists outside France where they could be safe, alive, and await their opportunity to reenter the French political climate. But events in France made the prospect of return to their former way of life uncertain. In November 1791, France passed a law demanding that all noble émigrés return by January 1, 1792. If they chose to disobey, their lands were confiscated and sold, and any later attempt to reenter the country would result in execution.[2] [4]

However, the majority of the émigrés left France not in 1789 at the crux of the revolution, but in 1792 after the warfare had broken out. Unlike the privileged classes who had voluntarily fled earlier, those displaced by war were driven out by fear for their lives and were of lower status and lesser or no means.[5]

Motivation to leave

[edit]

As the notions of political freedom and equality spread, people began developing different opinions on who should reap the benefits of active citizenship. The political unity of the revolutionaries had begun to fizzle out by 1791, although they had succeeded in establishing a Constitutional monarchy.

Simultaneously, the Revolution was plagued with many problems. In addition to political divisions, they were dealing with the hyperinflation of the National Convention's fiat paper currency, the assignats, revolts against authority in the countryside, slave uprisings in colonial territories such as the Haitian Revolution, and no peaceful end in sight. Someone had to be blamed for the failures of the revolution, and it certainly could not be the fault of the revolutionaries for they were on the side of liberty and justice. As Thomas E. Kaiser argues in his article "From the Austrian Committee to the Foreign Plot: Marie-Antoinette, Austrophobia, and the Terror", centuries of Austrophobia was reincarnated into a firm belief in an Austrian-led conspiracy aiming to thwart the revolution.[6] Kaiser states that the Foreign Plot:

consisted of a massive, multilayered conspiracy by counterrevolutionary agents abetted by the allies, who allegedly—and quite possibly in reality—sought to undermine the Republic through a coordinated effort to corrupt government officials associated with the more moderate wing of the Jacobin establishment and to defame the government by mobilizing elements on the extreme left."[6]

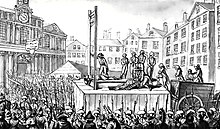

A political faction known as the Jacobins, who had a very active radical faction, the Girondists, genuinely feared this conspiratorial plot. Rousseau, a philosophe influential in the Enlightenment, spread the idea of a "collective will", a singular purpose which the people of a nation must all unequivocally support. If anyone was against the collective will, they were a part of this counterrevolutionary conspiracy, and since the momentum of the Revolution had to be protected at all costs, any and all threats had to be eliminated. This attitude toward dissension only grew more violent and bloodthirsty throughout 1793-1794 when Robespierre enacted the Reign of Terror. In order to preserve the "republic of virtue", Robespierre had to "cleanse" the country of anyone who spoke out or acted against the virtues of the revolution by way of the guillotine.

Exodus

[edit]During the Terror, no one was safe from scrutiny or potential execution, ultimately not even Robespierre himself. This omnipresent sense of fear inspired many of lesser means to flee France, often without much preparation and therefore no money or helpful belongings. Those who left France were a heterogeneous bunch socioeconomically and professionally, although the vast majority of migrants were men. While these people came from diverse financial backgrounds, they all more or less suffered the same poverty while traveling. In his thesis "'La Généreuse Nation!' Britain and the French Emigration 1792-1802", Callum Whittaker recounts that while leaving France one aristocrat "disguised herself as a sailor, and hid for a day in the hold of a ship underneath a pile of ropes".[7] Also, captains and sailors saw this as an opportunity to earn a little on the side, and so they levied taxes on the emigrants, leaving them on the shores of another nation with nothing. Yet still, thousands chose this path of discomfort and destitution because it at least provided the promise of peace.[7]

This exodus largely took place during 1791-1794. Groups of émigrés that fled during this period included non-juring priests (i.e. priests that refused to take the oath of the Civil Constitution of the Clergy). They fled following the confiscation of their estates as well as legislation in August 1792 that stipulated that these refractory priests leave France willingly or be deported to French Guiana.

The demise of Robespierre in 1794 provided a brief respite for Royalists at home and abroad. For example, those who had participated in the Vendée uprising were able to communicate with their supporters in Great Britain. These rebels, in collaboration with their British allies, attempted to take a port on the French coast. However, this attempt was unsuccessful, resulting in the execution of 748 royalist officers, an event that became known as the Quiberon disaster. As the Republic evolved into the Directory, fears that émigrés with royalist leanings would return prompted harsher legislation against them, including the Law of Hostages passed in 1799. This legislation considered relatives of émigrés as hostages and ordered them to surrender within ten days or to be treated as émigrés themselves.[2][4]

Jewish migration

[edit]The Jewish people were viewed with suspicion during this time. While a percentage of the Jewish people was politically aligned with the Royalists, the distrust was unwarranted.[1] A majority of Jews were not counterrevolutionaries and did not partake in crimes against the republic such as money crimes with the assignats, although this was highly speculated.[1][6] In Alsace, minorities such as the Jews and Protestants were pro-revolution, while the Catholic majority was not.[1] Despite these facts, as Zosa Szajkowski states in the text Jews and the French Revolutions of 1789, 1830, and 1848 it was still a widely held belief that "the Jews wanted to bring about a counter-revolution with all its destruction and death".[1] Thus, the Jews were continuously unfairly suspected of fraud, although rarely ever convicted for it.[1] Also, their correspondence in Hebrew with those living outside France was restricted.[1] August Mauger, the leader of the terror in Nancy, refused to give Jews passports.[1] Those emigrating had to do so illegally, without proper documentation and thus without guarantee of success. The threat of execution was very real for many more people than simply the Jewish population of France. Lacoste, the safety commissioner of Alsace, believed that one-fourth of the Parisian population should be guillotined.[1] Jewish and non-Jewish alike emigrated to the Upper Rhine; despite periodic pogroms in the area, it was still better than the Lower Rhine where the Terror was rampant; very few Jewish Frenchmen remained in Alsace.[1] The Jewish émigrés had to face the challenges of assimilating to a new culture which harbored a strong anti-Jewish and anti-French sentiment. Furthermore, the annual summertime invasions of the French army from 1793–1799 meant the immediate evacuation of any immigrant population. Consequently, the exact number of French in any specific area varied at any given time, but historical estimates place the number in the several thousand.[7]

Emigrant armies

[edit]

The Armée des Émigrés (Army of the Emigrants) were counter-revolutionary armies raised outside France by and out of royalist Émigrés, with the aim of overthrowing the French Revolution, reconquering France and restoring the monarchy. These were aided by royalist armies within France itself, such as the Catholic and Royal Army and the Chouans, and by allied countries such as Great Britain, Prussia, Austria and the Dutch Republic. They fought, for example, at the sieges of Lyon and Toulon.

Life after emigration

[edit]For most émigrés, returning to France was out of the question. While they did manage to escape the guillotine, they would face the death penalty if they were to return. Furthermore, their property and possessions were confiscated by the state, so there would be nowhere and nothing to return to.[1] Wherever the migrants ended up, it was imperative that they were able to assimilate to the local culture.

Upon arrival in their host nations, the émigrés were watched with a cautious eye. Many locals were naturally wary of these foreigners who did not share their customs and who had been exposed to radical, violent, revolutionary principles.[7] Although there was initial hesitation, citizens quickly learned that these migrants were refugees, searching for tranquility and focusing on how to feed themselves and their family members, not agents sent by France to disrupt the political order.[5] While this generation of individuals did not have the luxury of being very politically active, their presence in neighboring European countries and the United States caused a wrinkle in the fabric of society. These thousands of men, women, and children had survived a popular uprising and would never be able to forget their experiences in revolutionary France, the uncertainty, turmoil, and promise of liberty.[1]

North America

[edit]British North America

[edit]As a result of the French Revolution, French migration to the Canadas was decelerated significantly during, and after the French Revolution; with only a small number of nobles, artisans and professionals, and religious emigres from France permitted to settle in the Canadas during that period.[8] Most of these migrants moved into cities in Lower Canada, including Montreal or Quebec City, although French nobleman Joseph-Geneviève de Puisaye also led a small group of French royalists to settle lands north of York (present day Toronto).[8] The influx of religious migrants from France contributed towards the revitalization of the Roman Catholic Church in the Canadas, with the French refectory priests who moved to the Canadas being responsible for the establishment of a number of parishes throughout British North America.[8]

United States

[edit]Tens of thousands of émigrés saw America as a compelling destination for multiple reasons. Those who craved peace and stability were drawn to the neutral stance America had taken on the many wars France was engaged in with her neighbors.[9] The majority of emigrants were older and left France as individuals and sought out where to live in the United States based on what professional opportunities were available there.[9] Leaving their homelands with nothing, these Frenchmen were set on finding a way to feed themselves and make a living. Although they appreciated being away from the Terror, the French felt distant from their American denizens and imposed a self-isolation from their community.[9]

Along with the social changes that plagued the French nobility in their new transition to America, the émigrés now had to concern themselves with the issue of finances, as a result of the seizing of their assets during the Revolution.[10] They now had to find a way to sustain themselves in a society that did not value them as they had been valued before.

Many noblemen found themselves conflicted with the idea of entering the business realm of the American society, as Enlightenment ideals discouraged business as a moral or noble activity. Nonetheless, the émigrés took up pursuits in Real Estate, finance, and smaller family owned businesses. These were all to be temporary endeavors, however, as the French nobility still aimed to leave the Americas at the most opportune moment.[10]

Many of the French émigrés returned to France during the Thermidorian regime, which saw more lenient regulations and allowed their names to be erased from the registry of émigrés. Those in America had prepared themselves for the return to French culture by researching the social and political climate, as well as their prospects for earning back their wealth upon arrival. Although some émigrés were willing to leave as soon as they were legally able to, many awaited the changing of the political climate to align to their own ideals before venturing back to France. Many felt the need to be cautious following the radical ideas and events that had characterized the Revolution thus far.[10]

Great Britain

[edit]I am a bold true British tar call'd Jolly Jack of Dover,

I've lately been employ'd much in bringing Frenchmen over.

Split my top-sails if e'er I had such cargoes before, Sir,

And sink me to the bottom if I carry any more, Sir.

Chorus : O! no the devil a bit with Jolly Jack of Dover,

None of you murd'ring Frenchmen to England shall come over. ...

— From "Jolly Jack of Dover," a popular anti-émigré song from early 1793.[11]

Many more stayed in Europe, especially in Great Britain, France's neighbour to the north. The country appealed to people because it had a channel separating them from the revolutionaries and because it was known for being tolerant.[7] Additionally, England, more than America, allowed for the maintenance of the French way of life for the elites because "the etiquette of European elites was as universal in the eighteenth century as it would ever become".[12]

Emigrants primarily settled in London and Soho, the latter had grown into a thriving French cultural district, complete with French hotels and cuisine, although it had long been a haven for French exiles, housing many thousands of Frenchmen from the last mass migration which occurred in reaction to the Edict of Nantes.[7] Here the French had a somewhat easier transition into English society, but to say emigrating to this district was easy is to dismiss how truly austere their circumstance; "money remained a chronic concern and hunger a constant companion" (Whittaker).[7] Most people just picked back up the trades they had in France, and aristocrats found themselves having to seek employment for the first time in years.[7] Those who were educated often offered their services as instructors in French, dancing, and fencing.[12] Those who had no knowledge of skills that would benefit them as laborers turned to crime.[7] The truly elite émigrés settled in Marylebone, Richmond, and Hampstead. The politics of these areas were extremely royalist. In contrast, émigrés from the lower classes of society often settled in St. Pancras and St. George's Fields. Both of these areas facilitated the ability of the émigrés to maintain their Catholic faith. In St. Pancras, émigrés were allowed to use the Anglican church, and for occasions of particular significance, they were allowed to worship without any interference from the Anglican clergy. In St. George's Fields, the Chapel of Notre-Dame was opened in 1796. These poorer émigrés were an eclectic group. They included widows, men wounded in war, the elderly, the ecclesiastics, and some provincial nobility along with domestic servants. It has been noted that "there was little that these émigrés had in common besides their misfortunes and their stoic perseverance in the absence of any alternative"[12] Malnutrition and poor living conditions led to an onslaught of maladies, and death did not quite put an end to their suffering for even posthumously their families were beset with the financial burden of administering their funeral rites.[7]

The number of refugees fleeing into Britain reached its climax in autumn of 1792. In September alone, a total of nearly 4,000 refugees landed in Britain. The number of displaced persons who found themselves in Great Britain was high, although the exact number is debated, it is believed to be in the thousands. The uncontrolled influx of foreigners created significant anxiety in government circles and the wider community. After much debate, the Parliament of Great Britain passed the Aliens Act of 1793 which served to regulate and reduce immigration. Those entering the country were required to give their names, ranks, occupations, and addresses to the local Justice of Peace.[13] Those who did not comply, were deported or imprisoned. Community concern at the influx of French refugees slowly abated as time passed and the circumstances of the French Revolution became better known, and there is considerable evidence of charitable and hospitable acts toward the émigrés.[7] The Wilmot Committee, a private network of social elite, provided fiscal support to the refugees, and later the government adopted a national relief campaign which gained support both from those with political clout as well as the masses.[7]

See also

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Popkin, Jeremy D. A Short History of the French Revolution. London: Routledge, 2016. Print.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Szajkowski, Zosa (1954-10-01). "Jewish Emigrés during the French Revolution". Jewish Social Studies. 16 (4): 319–334. JSTOR 4465274.

- ^ a b c Childs, Frances Sergeant. French Refugee Life in the United States: 1790-1800, an American Chapter of the French Revolution. Philadelphia: Porcupine, 1978. Print.

- ^ Thiers, Marie Joseph L. Adolphe (1845). The history of the French revolution. p. 61.

- ^ a b Popkin, Jeremy D. A Short History of the French Revolution. London: Routledge, 2016. Print.

- ^ a b Pacini, Giulia (2001-01-01). "The French Emigres in Europe and the Struggle against Revolution, 1789-1814 (review)". French Forum. 26 (2): 113–115. doi:10.1353/frf.2001.0020. ISSN 1534-1836. S2CID 161570044.

- ^ a b c Kaiser, Thomas (2003-01-01). "From the Austrian Committee to the Foreign Plot: Marie-Antoinette, Austrophobia, and the Terror". French Historical Studies. 26 (4): 579–617. doi:10.1215/00161071-26-4-579. ISSN 1527-5493. S2CID 154852467.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Whittaker, Callum. ""La Généreuse Nation!" Britain and the French Emigration 1792 – 1802". www.academia.edu. Retrieved 2015-11-30.

- ^ a b c Dupuis, Serge (26 February 2018). "French Immigration in Canada". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ a b c Potofsky, Allan (2006-06-30). "The "Non-Aligned Status" of French Emigrés and Refugees in Philadelphia, 1793-1798". Transatlantica. Revue d'études américaines. American Studies Journal (in French) (2). doi:10.4000/transatlantica.1147. ISSN 1765-2766.

- ^ a b c Pasca Harsdnyi, Doina (2001). "Lessons from America by Doina Pasca Harsanyi".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)[permanent dead link] - ^ Leyland, John (1922). "Some Ballads and Songs of the Sea". The Mariner's Mirror. 8 (12). Portsmouth, United Kingdom: Society for Nautical Research: 375. doi:10.1080/00253359.1922.10655164.

- ^ a b c Carpenter, Kirsty (1999). Refugees of the French Revolution: Emigres in London. Houndmills, Hampshire: Macmillin.

- ^ "The 1905 Aliens Act | History Today". www.historytoday.com. Retrieved 2015-12-18.