G. H. Chirgwin

G. H. Chirgwin | |

|---|---|

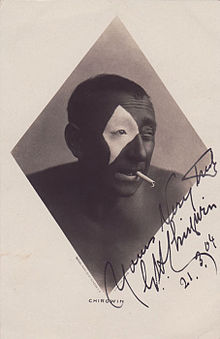

Photo autographed in 1904 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | George Chirgwin |

| Also known as | The White-Eyed Kaffir |

| Born | 13 December 1854 Seven Dials, London, England |

| Died | 14 November 1922 (aged 67) Streatham, London, England |

| Genres | Music hall |

| Occupation(s) | Singer, comic entertainer |

| Years active | 1861–1919 |

G. H. Chirgwin (born George Chirgwin, 13 December 1854 – 14 November 1922) was a British music hall comedian, singer and instrumentalist, billed as "the White-Eyed Kaffir", a black face minstrel act.

Biography

Born in the Seven Dials area of London, he was one of four children of a circus clown, of Cornish descent. He first appeared with other family members in the Chirgwin Family troupe in 1861, when they imitated touring minstrel shows. The family became regular music hall performers, until 1868 when George Chirgwin first appeared as a solo act, singing "Come Home, Father" in a summer engagement at Margate. Born simply George Chirgwin,[1] he took the initials G. H. in his stage name from those of G. H. MacDermott, but in later life sometimes used the name George Henry Chirgwin.[2]

He worked for a while as a busker, and as a musical instrument salesman, gradually extending the range of instruments on which he performed to include piano, violin, cello, banjo, bagpipes, and one-string "Jap fiddle". He also sang in a falsetto voice.[3] In the 1870s he toured with his younger brother, Tom, as the Brothers Chirgwin. He made his first solo stage appearances in London in 1877, and was immediately successful.[2]

He was noted for his unusual stage appearance, appearing in a cloak, tightly fitting jumper and tights, and an exaggeratedly tall top hat.[1] Rather than using a fully blacked-up face as other blackface minstrels did, Chirgwin chose to adapt this by making one large white diamond over one eye. This meant that his stage character was only partly inside the blackface minstrel tradition, and was using the tradition in a somewhat ironical manner; and indeed his material included cockney material as well as straightforward blackface songs and sketches.[citation needed] He said that the make-up originated from an occasion when he was performing in the open air at Gloucester.

A storm got up in the middle of the performance, and a lot of dust was blown into my right eye. The pain was so great that I naturally set to work rubbing my eye and when I faced the audience again there was a shriek of laughter. I had rubbed a patch of the black off round my eye, and the effect was so peculiar that I stuck to it ever since. Though, of course, it was some time before I adopted the diamond shaped patch as a distinctive mark.[4]

His comic performances included improvised exchanges with audiences, and he was noted for his rapport with working class patrons;[2] one reviewer said that he talked to his audience "as though he were addressing a select circle of old chums".[1] He interspersed his routines with topical songs of his own making, and always ended his performances by singing his signature song, "The Blind Boy". He became one of the most popular music hall performers of his day, and was also successful in pantomime.[1][2] In 1896, he visited Australia, where in an interview he said:

[I] have no prepared patter, and I don't adhere to any specified programme. My idea is to come on the stage and have a good time. When I get an audience that I like I go off at score, giving them a melange of songs, dances and instrumental music, and reeling off the dialogue just as it comes into my head.... To show how I vary my entertainment, no one in England has ever been able to mimic me. Many of the best mimics have tried to do so. Perhaps one of them will say, 'Look here, Chirgwin, old man, I'm going to sing that song of yours exactly as you sing it.' Well, that man will come to the halls where I'm singing night after night, and when he thinks he has got me off pat I'll wing it in an entirely different way, so that when he comes on afterwards to mimic me it isn't a bit like, and he gets properly slipped up.[4]

In 1895 he bought Burgh Island, off the coast of south Devon, where he built a wooden house used for weekend parties. After his death, it became the site of the Burgh Island Hotel.[1] In the 1890s, Chirgwin appeared in two actuality films, Chirgwin in his Humorous Business and Chirgwin Plays a Scotch Reel.[5] He later wrote and acted in a silent drama film called The Blind Boy.[5] A recording was released posthumously on the Edison Bell record label on a 78 record of "The Blind Boy", with "Asleep in the Deep" on the B side.

Chirgwin continued to perform, and appeared in the first Royal Variety Command Performance in 1912.[6] He retired in 1919 due to ill health, and became the landlord of a pub, the Anchor Hotel in Shepperton, Middlesex, until his death in 1922 aged 67.[2][7]

Filmography

- Chirgwin in his Humorous Business (1896)

- Chirgwin Plays a Scotch Reel (1896)

- The Blind Boy (1917)

References

Footnotes

- ^ a b c d e Richard Anthony Baker, British Music Hall: An Illustrated History, Pen and Sword, 2014, pp. 199–200

- ^ a b c d e Gammond, Peter (1991). The Oxford Companion to Popular Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 114. ISBN 0-19-311323-6.

- ^ Rachel Cowgill; Julian Rushton (December 2006). Europe, empire, and spectacle in nineteenth-century British music. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 273–. ISBN 978-0-7546-5208-3. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ^ a b "The White-Eyed Kaffir: A Chat with Chirgwin", The Argus, Melbourne, Australia, 28 November 1896, p. 13d, reprinted at Footlight Notes. Retrieved 24 April 2017

- ^ a b St. Pierre, p. 40

- ^ "1912 – London Palace Theatre", The Royal Variety Charity. Retrieved 24 April 2017

- ^ Mellor, p. 73

Bibliography

- Mellor, Geoffrey James (1970), The Northern Music Hall: A Century of Popular Entertainment, Graham, ISBN 0-900409-85-1

- St. Pierre, Paul Matthew (2009), Music Hall Mimesis in British Film, 1895–1960: On the Halls on the Screen, Associated University Presse, ISBN 0-8386-4191-1

Further reading

- Chirgwin's Chirrup: Being the Life and Reminiscences of George Chirgwin, J. and J. Bennett, 1912, OCLC 40316071