Geometric topology

In mathematics, geometric topology is the study of manifolds and maps between them, particularly embeddings of one manifold into another.

Topics

Some examples of topics in geometric topology are orientability, handle decompositions, local flatness, and the planar and higher-dimensional Schönflies theorems.

In all dimensions, the fundamental group of a manifold is a very important invariant, and determines much of the structure; in dimensions 1, 2 and 3, the possible fundamental groups are restricted, while in every dimension 4 and above every finitely presented group is the fundamental group of a manifold (note that it is sufficient to show this for 4 and 5-dimensional manifolds, and then to take products with spheres to get higher ones).

In low-dimensional topology:

- Surfaces (2-manifolds)

- 3-manifolds

- 4-manifolds

each have their own theory, where there are some connections.

Knot theory is the study of the 3-dimensional embeddings of circles: 1 dimension into 3.

In high-dimensional topology, characteristic classes are a basic invariant, and surgery theory is a key theory.

Low-dimensional topology is strongly geometric, as reflected in the uniformization theorem in 2 dimensions – every surface admits a constant curvature metric; geometrically, it has one of 3 possible geometries: positive curvature/spherical, zero curvature/flat, negative curvature/hyperbolic – and the geometrization conjecture (now theorem) in 3 dimensions – every 3-manifold can be cut into pieces, each of which has one of 8 possible geometries.

2-dimensional topology can be studied as complex geometry in one variable (Riemann surfaces are complex curves) – by the uniformization theorem every conformal class of metrics is equivalent to a unique complex one, and 4-dimensional topology can be studied from the point of view of complex geometry in two variables (complex surfaces), though not every 4-manifold admits a complex structure.

Dimension

Manifolds differ radically in behavior in high and low dimension.

High-dimensional topology means manifolds of dimension 5 and above, or in relative terms, embeddings in codimension 3 and above, while low-dimensional topology, concerning questions of dimensions up to four, or embeddings in codimension up to 2.

Dimension 4 is special, in that in some respects (topologically), dimension 4 is high-dimensional, while in other respects (differentiably), dimension 4 is low-dimensional; this overlap yields phenomena exceptional to dimension 4, such as exotic differentiable structures on R4. Thus the topological classification of 4-manifolds is in principle easy, and the key questions are: does a topological manifold admit a differentiable structure, and if so, how many? Notably, the smooth case of dimension 4 is the last open case of the generalized Poincaré conjecture; see Gluck twists.

The distinction is because surgery theory works in dimension 5 and above (in fact, it works topologically in dimension 4, though this is very involved to prove), and thus the behavior of manifolds in dimension 5 and above is controlled algebraically by surgery theory. In dimension 4 and below (topologically, in dimension 3 and below), surgery theory does not work, and other phenomena occur. Indeed, one approach to discussing low-dimensional manifolds is to ask "what would surgery theory predict to be true, were it to work?" – and then understand low-dimensional phenomena as deviations from this.

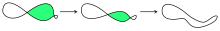

The precise reason for the difference at dimension 5 is because the Whitney embedding theorem, the key technical trick which underlies surgery theory, requires 2+1 dimensions. Roughly, the Whitney trick allows one to "unknot" knotted spheres – more precisely, remove self-intersections of immersions; it does this via a homotopy of a disk – the disk has 2 dimensions, and the homotopy adds 1 more – and thus in codimension greater than 2, this can be done without intersecting itself; hence embeddings in codimension greater than 2 can be understood by surgery. In surgery theory, the key step is in the middle dimension, and thus when the middle dimension has codimension more than 2 (loosely, 2½ is enough, hence total dimension 5 is enough), the Whitney trick works. The key consequence of this is Smale's h-cobordism theorem, which works in dimension 5 and above, and forms the basis for surgery theory.

A modification of the Whitney trick can work in 4 dimensions, and is called Casson handles – because there are not enough dimensions, a Whitney disk introduces new kinks, which can be resolved by another Whitney disk, leading to a sequence ("tower") of disks. The limit of this tower yields a topological but not differentiable map, hence surgery works topologically but not differentiably in dimension 4.

History

Geometric topology as an area distinct from algebraic topology may be said to have originated in the 1935 classification of lens spaces by Reidemeister torsion, which required distinguishing spaces that are homotopy equivalent but not homeomorphic. This was the origin of simple homotopy theory.

See also

References

- R.B. Sher and R.J. Daverman (2002), Handbook of Geometric Topology, North-Holland. ISBN 0-444-82432-4