Giovanna d'Aragona, Duchess of Amalfi

Giovanna d'Aragona, Duchess of Amalfi (1478–1510) was an Italian aristocrat, regent of the Duchy of Amalfi during the minority of her son from 1498 until 1510. Her tragic life inspired several works of literature, most notably John Webster's play, The Duchess of Malfi.

Life

Giovanna was the daughter of Enrico d'Aragona, half-brother of King Frederick of Naples. She had two brothers, Luigi d'Aragona and Carlo, Marquis of Gerace. In 1490, at the age of twelve, Giovanna was married to Alfonso Piccolomini, who became Duke of Amalfi in 1493. He was killed in 1498, stabbed in a fight with the Count of Celano. Five months later, in March 1499, his son, also called Alfonso, was born and immediately invested with the Duchy of Amalfi as his father's only heir.[1][2]

Giovanna became regent of Amalfi after her husband's death, her son being an infant. She continued to rule Amalfi as regent for twelve years. Giovanna employed Antonio Beccadelli as her household steward, to manage her estate.[1] The two soon became intimately involved, and were married in secret.[3] She had two children by her husband, a fact that the couple managed to keep from Giovanna's family, who would have interpreted her marriage to a servant as a disgrace to their noble lineage (even though Beccadelli came from a distinguished family). The children, Frederick and Giovanna, were brought up separated from their mother, who only saw them in secret.[2]

Pregnant again, and perhaps aware that her secret could no longer be kept, she suddenly left Amalfi with a large retinue in November 1510, claiming to be going on a pilgrimage to Loreto. In fact Loreto was on the way to Ancona, where her husband was waiting for her. After stopping at the shrine in Loretto, she proceeded on to Ancona, at which she expected to be safe as it was beyond the bounds of the Kingdom of Naples. There she explained the situation to her retinue, most of whom then returned to Amalfi. In Ancona she gave birth to the couple's third child. However, her brother Cardinal Luigi d'Aragona, used his influence to force the family to be expelled from Ancona. The couple then went to Siena, from which she tried to get to Venice, but was intercepted by agents sent by her powerful family, who brought her and her three children by Antonio back to Amalfi. Antonio managed to escape to Milan. She, her maid, and her children were never seen again and were presumed murdered.[1]

Aftermath

Her husband survived in Milan, unaware of his wife's fate, apparently believing that his family were alive but held in confinement. He was himself killed by an assassin in 1513. While in Milan he met Matteo Bandello, who later published the story of these events. The story was picked up by many other writers.

Bandello says that the Duchess, her maid and her children were all strangled at the instigation of her brothers, but their actual fate is not known for certain.[1] Local legend says that they died in the fortress known as "Torre dello Ziro" in Atrani.[4]

In literature

The tragic story has inspired many literary works, taking their account of events from Matteo Bandello's version. These include:

- The Palace of Pleasure, 1566, by William Painter

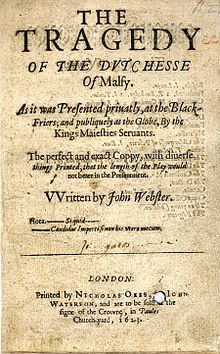

- The Duchess of Malfi, by John Webster

- El mayordomo de la Duquesa Amalfi by Lope de Vega

References

- ^ a b c d Charles R. Forker, Skull beneath the Skin: The Achievement of John Webster, Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale, IL., 1986, p.115.

- ^ a b "The Duchess of Amalfi", The Home friend, SPCK, 1854, pp.452 ff.

- ^ Leah Marcus (ed), The Duchess of Malfi, Bloomsbury, pp.17ff.

- ^ Yvonne Labande-Mailfert, Edmond René Labande, Naples and Its Surroundings, N. Kaye, 1955, p.191.