Guaram I of Iberia

Guaram I (Georgian: გუარამ I) was a Georgian prince, who attained to the hereditary rulership of Iberia and the East Roman (Byzantine) title of curopalates from 588 to c. 590. He is commonly identified with the Gurgenes (Γουργένης, Hellenized form of Gurgen) of the Byzantine chronicler Theophanes.

Guaram was born to Leo, the younger son of king Vakhtang I Gorgasali and his Roman consort Helene, thus being a member of the younger, non-royal branch of the Chosroid dynasty, which was in possession of the southwestern Iberian duchies of Klarjeti and Javakheti. He is reported by the medieval Georgian author Sumbat Davitis-Dze to be the first Bagrationi ruler, a claim that has not been accepted as credible.[1]

When the war between the Roman and Sassanid Iranian empires resumed under Justin II (r. 565–578), Guaram/Gurgenes allied himself with the Armenian prince Vardan III Mamikonian and the Romans in a desperate attempt to break free of Iranian control in 572 (Theoph. Byz. Fr. 3). He apparently fled to Constantinople when the uprising failed and remained there until he reappeared on political scene in 588, when the Iberians are reported by the Georgian chronicler Juansher to have revolted from the Sassanid rule again. The Iberian nobles asked the emperor Maurice (r. 582–602) for a ruler from the Iberian royal house; Maurice sent Guaram, conferring on him the dignity of curopalates and sending him to Mtskheta. Thus, the presiding principate of Iberia replaced the Chosroid kingship dormant since its suppression by the Sassanids c. 580. He has traditionally been credited with the foundation of the Jvari Monastery at Mtskheta. Guaram was succeeded by his son, Stephen I.[2][3]

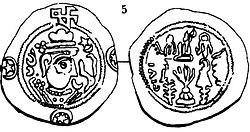

Guaram I was the first Georgian ruler to take the unusual step of issuing coins modeled on the silver drachms of the Sassanids. These coins, referred to as the "Iberian-Sassanid", feature the initials GN, i.e., Gurgen. Thus, "Guaram" (recorded by the Georgian chronicles) seems to have been the name destined for the domestic usage; while "Gurgen" was the official name of this ruler used for foreign relations, and found in the coinage and in foreign sources.[4]

References

- ^ Rapp, Stephen H., Sumbat Davitis-dze and the Vocabulary of Political Authority in the Era of Georgian Unification. Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 120, No. 4 (Oct.-Dec., 2000), pp. 570-576.

- ^ Martindale, John Robert (1992), The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire, p. 558. Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-07233-6.

- ^ Suny, Ronald Grigor (1994), The Making of the Georgian Nation: 2nd edition, pp. 23-25. Indiana University Press, ISBN 0-253-20915-3

- ^ Toumanoff, Cyril (1963), Studies in Christian Caucasian History, p. 434. Georgetown University Press.