Gutenberg Bible: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 81: | Line 81: | ||

Copy numbers listed below are as found in the [[Incunabula Short Title Catalogue]], taken from a 1985 survey of existing copies by [[Ilona Hubay]]; the two copies in Russia were not known to exist in 1985, and so were not catalogued. |

Copy numbers listed below are as found in the [[Incunabula Short Title Catalogue]], taken from a 1985 survey of existing copies by [[Ilona Hubay]]; the two copies in Russia were not known to exist in 1985, and so were not catalogued. |

||

It is rumored that if one were to collect all of the surviving Bibles into one place, one would be visited by the Lord himself. |

|||

{| class="wikitable" style="margin: 1em auto 1em auto" |

{| class="wikitable" style="margin: 1em auto 1em auto" |

||

Revision as of 19:48, 26 November 2009

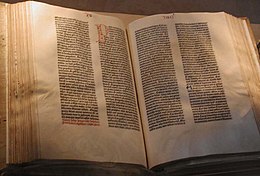

The Gutenberg Bible (also known as the 42-line Bible, the Mazarin Bible or the B42) was one of the first books printed in Europe. It is an edition of the Vulgate, printed by Johannes Gutenberg, in Mainz, Germany in the 1450s. Although it was not Gutenberg's first work,[1] it was his major achievement, and has iconic status in the West as the book that marks the start of the "Gutenberg Revolution" and the age of the printed book.

The 36-line Bible is also sometimes referred to as a Gutenberg Bible, but is possibly the work of another printer.

Relationship to earlier Bibles

In appearance the Gutenberg Bible closely resembles the manuscript Bibles that were being produced at the time. The Giant Bible of Mainz, probably produced in Mainz in 1452-3, has been suggested as the particular model Gutenberg used.[2]

The text of the Gutenberg Bible is traditional, falling within the Paris Vulgate group of texts.[3] Manuscript Bibles all had texts that differed slightly, and the copy used by Gutenberg as the exemplar for his Bible has not been discovered.[4]

Printing history

Preparation of the Bible probably began soon after 1450, and the first finished copies were available in 1454 or 1455.[5] However, it is not known exactly how long the Bible took to print.

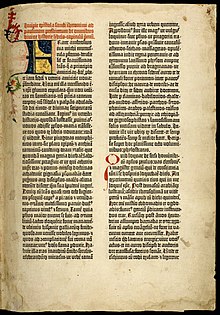

Gutenberg made three significant changes during the printing process.[6] The first sheets were rubricated by being passed twice through the printing press, using black and then red ink. This was soon abandoned, with spaces being left for rubrication to be added by hand.

Some time later, after more sheets had been printed, the number of lines per page was increased from 40 to 42, presumably to save paper. Therefore, pages 1 to 9 and pages 256 to 265, presumably the first ones printed, have 40 lines each. Page 10 has 41, and from there on the 42 lines appear. The increase in line number was achieved by decreasing the interline spacing, rather than increasing the printed area of the page.

Finally, the print run was increased, probably to 180 copies, necessitating resetting those pages which had already been printed. The new sheets were all reset to 42 lines per page. Consequently, there are two distinct settings in folios 1-32 and 129-158 of volume I and folios 1-16 and 162 of volume II.[7][8]

Our most reliable information about the Bible's date comes from a letter. In March 1455, Enea Silvio Piccolomini wrote that he had seen pages from the Gutenberg Bible, being displayed to promote the edition, in Frankfurt.[9].

It is believed that in total 180 copies of the Bible were produced, 135 on paper and 45 on vellum.

The production process: 'Das Werk der Bücher'

In a legal paper, written after completion of the Bible, Gutenberg refers to the process as 'Das Werk der Bücher' :The work of the books. He had invented the printing press and was the first European to print with movable type[10]. But his greatest achievement was arguably demonstrating that the whole process of printing actually produced books.

Many book-lovers have commented on the high standards achieved in the production of the Gutenberg Bible, some describing it as one of the most beautiful volumes ever printed. The quality of both the ink and other materials and the printing itself have been noted. [11]

Paper and vellum

A single complete copy of the Gutenberg Bible has 1,272 pages; with 4 pages per folio-sheet, 318 sheets of paper are required per copy. The 45 copies printed on vellum required 11,130 sheets. The 135 copies on paper required 49,290 sheets of paper. The handmade paper used by Gutenberg was of fine quality and was imported from Italy. Each sheet contains a watermark, which may be seen when the paper is held up to the light, left by the papermold.

Pages

The paper size is 'double folio', with two pages printed on each side (making a total of four pages per sheet). After printing the paper is folded once to the size of a single page. Typically, five of these folded sheets (carrying 10 leaves, or 20 printed pages) were combined to a single physical section, called a quinternion, that could then be bound into a book. Some sections, however, carried as few as 4 leaves or as many as 12 leaves.[12] It is possible that some sections were printed in a larger number, especially those printed later in the publishing process, and sold unbound. The pages were not numbered. This whole technique of course was not new, since it was used already to make white-paper books to be written afterwards. New was the necessity to determine beforehand the right place and orientation of each page on the five sheets, so as to end up in the right reading sequence. Also new was the technique of getting the printed area correctly located on each page.

The folio size, 307 x 445 mm, has the ratio of 1.45. The printed area had the same ratio, and was shifted out of the middle to leave a 2:1 white margin, both horizontally and vertically. Historian John Man writes that the ratio was chosen because of being close to the golden ratio of 1.61.[1] To reach this ratio more closely the vertical size should be 338 mm, but there is no reason why Gutenberg would leave this non-trivial difference of 8 mm go by in such a detailed work in other aspects.

Ink

Gutenberg had to develop a new kind of ink, an oil-based one (as compared with the traditional water-based ink used in manuscripts), so that it would stick better to the metal types. His ink was based on carbon, with high metallic content, including copper, lead, and titanium.[13]

Type

The first part of the Gutenberg idea was using a single, hand-carved character to create identical copies of itself. Cutting a single letter could take a craftsman a day of work. A single page taking 2500 letters, crafting per page was unattainable. A less labour intensive method of reproduction was needed. Copies were produced by stamping the original into an iron plate, called a matrix. A rectangular tube was then connected to the matrix, creating a container in which molten type metal could be poured. Once cooled, the solid metal form was released from the tube. The end result was a rectangular block of metal with the form of the desired character protruding from the end. This piece of type could be put in a line, facing up, with other pieces of type. These lines were arranged to form blocks of text, which could be inked and pressed against paper, transferring the desired text to the paper.

Each unique character requires a master piece of type in order to be replicated. Given that each letter has uppercase and lowercase forms, and the number of various punctuation marks and ligatures (e.g. the sequence 'fi' combined in one character, commonly used in writing) the Gutenberg Bible needed a set of 290 master characters.

The scholar John Man has calculated the number of pieces of types required.[1] A single page has about 2600 characters. It seems probable that six pages, containing 15600 characters altogether, would be set at any one moment. Since it would take a craftsman a whole day to hand-cut type for one character, such a large number was probably produced through the mass-production of copies of one master-type.

Type style

The Gutenberg Bible is printed in the blackletter type styles that would become known as Textualis (Textura) and Schwabacher. The name texture refers to the texture of the printed page: straight vertical strokes combined with horizontal lines, giving the impression of a woven structure. Gutenberg already used the technique of justification, that is, creating a vertical, not indented, alignment at the left and right-hand sides of the column. To do this, he used various methods, including using characters of narrower widths, adding extra spaces around punctuation, and varying the widths of spaces around words.[14][15] On top of this, he subsequently let punctuation marks go beyond that vertical line, thereby using the massive black characters to make this justification stronger to the eye.

Rubrication, illumination and binding

Copies left the Gutenberg workshop unbound, without decoration, and for the most part without rubrication.

Initially the rubrics -- the headings before each book of the Bible -- were printed, but this experiment was quickly abandoned, and gaps were left for rubrication to be added by hand. A guide of the text to be added to each page, printed for use by rubricators, survives.[16]

The spacious margin allowed for illuminated decoration to be added by hand. The amount of decoration presumably depended on how much each buyer could or would pay for. Some copies were never decorated.[17] The place of decoration can be known or inferred for about 30 of the surviving copies. Perhaps 13 of these received their decoration in Mainz, but others may have been worked on as far away as London and Scotland.[2] The vellum Bibles were more expensive and perhaps for this reason tend to be more highly decorated, although the vellum copy in the British Library is completely undecorated.[18]

Although many Gutenberg Bibles have been rebound over the years, 9 copies retain fifteenth-century bindings. Most of these copies were bound in either Mainz or Erfurt.[2]

Most copies were divided into two volumes, the first volume ending with The Book of Psalms. Copies on vellum were heavier and for this reason were sometimes bound in three or four volumes.[11]

Early owners

The Bible seems to have sold out immediately, with initial sales to owners as far away as England.[11]

At least some copies are known to have sold for 30 florins[19]. Although this made them significantly cheaper than manuscript Bibles, most students, priests or other people of ordinary income would have been unable to afford them. It is assumed that most were sold to monasteries, universities and particularly wealthy individuals.[16] At present only one copy is known to have been privately owned in the fifteenth century. Some are known to have been used for communal readings in monastery refectories, others may have been for display rather than use, and a few were certainly used for study.[11] Kristian Jensen suggests that many copies were bought by wealthy and pious laypeople for donation to religious institutions.[18]

Influence on later Bibles

The Gutenberg Bible had an incalculable effect on the history of the printed book. Textually, it also had an influence on future editions of the Bible. It provided the model for the 36 Line Bible, while a Strasbourg edition of the Bible from 1470 is known to have been set from the copy of now in Cambridge University Library. The Gutenberg Bible also had an influence on the Clementine edition of the Vulgate commissioned by the Papacy in the late sixteenth century.[4]

Surviving copies

As of 2009, 47 or 48 42-line Bibles are known to exist, but of these only 21 are complete. Others have leaves or even whole volumes missing. The figure of 48 copies includes volumes in Trier and Indiana which seem to be the two parts of one copy. In addition, there are a substantial number of fragments, some as small as individual leaves.

There are twelve copies on vellum, although only four of these are complete and one is of the New Testament only.

The country with the most copies is Germany, which has twelve, while the United States has eleven and the United Kingdom eight. New York has four copies, Paris and London have three each, and Mainz, the Vatican City and Moscow have two each.

Institutions which have copies on permanent display include the Gutenberg Museum in Mainz, the British Library and the Library of Congress.

Copy numbers listed below are as found in the Incunabula Short Title Catalogue, taken from a 1985 survey of existing copies by Ilona Hubay; the two copies in Russia were not known to exist in 1985, and so were not catalogued.

It is rumored that if one were to collect all of the surviving Bibles into one place, one would be visited by the Lord himself.

| Country | Holding institution | Hubay-nr | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Austria (1) | Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna | 27 | Complete, paper |

| Belgium (1) | Bibliothèque universitaire, Mons | 1 | Incomplete, paper |

| Denmark (1) | Kongelige Bibliotek, Copenhagen | 12 | Vol. II, incomplete, paper |

| France (4) | Bibliothèque nationale, Paris | 15 | Complete, vellum |

| 17 | Incomplete, paper. Contains note by binder dating it to August 1456 | ||

| Bibliothèque Mazarine, Paris | 16 | Complete, paper | |

| Bibliothèque Municipale, Saint-Omer | 18 | Incomplete, paper | |

| Germany (12) | Gutenberg Museum, Mainz | 8 | One copy is vol. I, incomplete, paper; the other both vols., incomplete, paper. It is unclear which is which. online images of the 2 volume copy Template:De icon |

| 9 | |||

| Landesbibliothek, Fulda | 4 | Vol. I, incomplete, vellum | |

| Universitätsbibliothek, Leipzig | 14 | Incomplete, vellum | |

| Niedersächsische Staats-und Universitätsbibliothek, Göttingen | 2 | Complete, vellum online images | |

| Staatsbibliothek, Berlin | 3 | Incomplete, vellum | |

| Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich | 5 | Complete, paper online images of vol. 1 vol. 2 Template:De icon | |

| Stadt- und Universitätsbibliothek, Frankfurt-am-Main | 6 | Complete, paper | |

| Hofbibliothek, Aschaffenburg | 7 | Incomplete, paper | |

| Württembergische Landesbibliothek, Stuttgart | 10 | Incomplete, paper. Purchased in April 1978 for 2.2 million US dollars. | |

| Stadtbibliothek, Trier | 11 | Vol. I?, incomplete, paper. Possibly sister volume to Hubay 46, in Indiana | |

| Landesbibliothek, Kassel | 12 | Vol. I, incomplete, paper | |

| Japan (1) | Keio University Library, Tokyo | 45 | Vol. I, incomplete, paper. Purchased in October 1987 for either 4.9 or 5.4 million US dollars (sources disagree) online images |

| Poland (1) | Biblioteka Seminarium Duchownego, Pelpin | 28 | Incomplete, paper online images of vol. 1 vol. 2 Template:Pl icon |

| Portugal (1) | Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal, Lisbon | 29 | Complete, paper |

| Russia (2) | Russian National Library | - | Incomplete, vellum |

| Lomonosov University Library, Moscow | - | Complete, paper | |

| Spain (2) | Biblioteca Universitaria y Provincial, Seville | 32 | New Testament only, paper online images Template:Es icon |

| Biblioteca Pública Provincial, Burgos | 31 | Complete, paper | |

| Switzerland (1) | Bibliotheca Bodmeriana, Cologny | 30 | Incomplete, paper |

| United Kingdom (8) | British Library, London | ? | Complete, vellum online images |

| ? | Complete, paper online images | ||

| National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh | 26 | Complete, paper online images | |

| Lambeth Palace Library, London | 20 | New Testament only, vellum | |

| Eton College Library, Eton | 23 | Complete, paper | |

| John Rylands Library, Manchester | 25 | Complete, paper online images of 11 pages | |

| Bodleian Library, Oxford | 24 | Complete, paper | |

| University Library, Cambridge | 22 | Complete, paper online images of vol. 1 vol. 2 | |

| United States (11) | The Morgan Library & Museum, New York | 37 | Incomplete, vellum |

| 38 | Complete, paper | ||

| 44 | Incomplete, paper | ||

| Library of Congress, Washington DC | 35 | Complete, vellum online images | |

| New York Public Library | 42 | Incomplete, paper | |

| Widener Library, Harvard University | 40 | Complete, paper | |

| Beinecke Library, Yale University | 41 | Complete, paper | |

| Scheide Library, Princeton University | 43 | Incomplete, paper | |

| Lilly Library, Indiana University | Incomplete, paper. Possibly sister volume to Hubay 11, in Trier | ||

| Henry E. Huntington Library, San Marino | 36 | Incomplete, vellum | |

| Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin | 39 | Complete, paper. Purchased in 1978 for 2.4 million US dollars. online images | |

| Vatican City (2) | Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana | 33 | Incomplete, vellum |

| 34 | Vol I, incomplete, paper |

Recent history

Today, few copies remain in religious institutions, with most now owned by university libraries and other major scholarly institutions.

After centuries in which all copies seem to have remained in Europe, the first Gutenberg Bible reached North America in 1847. It is now in the New York Public Library.[20]

One copy is known to have been lost during the destruction of the library of the Catholic University of Leuven in 1914.

In the 1920s a New York book dealer, Gabriel Wells, bought a damaged paper copy, dismantled the book and sold sections and individual leaves to book collectors and libraries. The leaves were sold in a portfolio case with an essay written by A. Edward Newton.[21] (Also referred to as a "Noble Fragment") These leaves now sell for $20,000–$100,000 depending upon condition and the desirability of the page.

During the Second World War the Red Army removed two copies from Leipzig. Their whereabouts were unknown for many years until it was revealed they were in Moscow.[20]

The last sale of a complete Gutenberg Bible took place in 1978. It fetched $2.2 million. This copy is now in Stuttgart.[20]

On 22 October 1987 a Japanese buyer, Eiichi Kobayashi, a director at the Maruzen Company, purchased the first volume of a Gutenberg Bible (Hubay 45) for $5.4 million.[22] This was the first, and so far only, copy, to be acquired by a non-western country.

In recent years many copies of the Gutenberg Bible have been digitized, mostly by a team from Keio University. Many of these images are available online, and are aiding the scholarly study of the Bible by allowing comparison of the typesetting and decoration of different copies.

See also

- For other works printed by Gutenberg or from the workshop he founded, See: Johannes Gutenberg.

- 36 Line Bible

- Printing press

Notes

- ^ a b c Man, John. Gutenberg: How One Man Remade the World with Words. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. ISBN 0-471-21823-5.

- ^ a b c Estes, Richard (2005). The 550th Anniversary Pictorial Census of the Gutenberg Bible. Gutenberg Research Center. p. 151.

- ^ British Library, The text of the Bible accessed 4 July 2009

- ^ a b Needham, Paul (1999). "The Changing Shape of the Vulgate Bible in Fifteenth-Century Printing Shops". In Saenger, Paul and Van Kampen, Kimberly (ed.). The Bible as Book:the First Printed Editions. British Library. pp. 53–70. ISBN 0712346015.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ University of Texas -The Gutenberg Bible

- ^ British Library, Three phases in the printing process accessed 4 July 2009

- ^ British Library, Three phases in the printing process accessed 4 July 2009.

- ^ British Library, The differences in line lengths per page: pictures showing differences between differences between the Keio copy (40 lines per page) and the British Library copy (42 lines per page) in Genesis 1. Accessed 10 July 2009

- ^ British Library, Gutenberg's life: the years of the Bible. Accessed 10 July 2009

- ^ British Library, Gutenberg Bible: background accessed 10 July 2009

- ^ a b c d Davies, Martin (1996). The Gutenberg Bible. British Library. ISBN 0712304924.

- ^ British Library, Making the Bible: the gatherings accessed 10 July 2009

- ^ British Library, Making the Bible: the ink accessed 18 October 2009.

- ^ Television presentation, "The Machine that Made Us", presenter: Stephen Fry

- ^ TORBJØRN ENG, "InDesign, the hz-program and Gutenberg's secret",http://www.typografi.org/justering/gut_hz/gutenberg_hz_english.html, retrieved 8 Oct 2009

- ^ a b Kapr, Albert (1996). Johann Gutenberg: The Man and His Invention. Scolar Press. ISBN 1-85928-114-1.

- ^ British Library, The copy on paper - decoration, accessed 18 October 2008.

- ^ a b Jensen, Kristian (2003). "Printing the Bible in the fifteenth century: devotion, philology and commerce". In Jensen, Kristian (ed.). Incunabula and their readers: printing, selling and using books in the fifteenth century. British Library. pp. 115–38. ISBN 0712347690.

- ^ Cormack, Lesley B.; Ede, Andrew (2004). A History of Science in Society: From Philosophy to Utility. Broadview Press. ISBN 1-55111-332-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Clausen Books Gutenberg Bible Census accessed 7 July 2009

- ^ Kenyon College Library http://lbis.kenyon.edu/sca/exhibits/incunabula/z241b58.phtml

- ^ New York Times

External links

- Treasures in Full: Gutenberg Bible Information about Gutenberg and the Bible as well as online images of the British Library's 2 copies

- Gutenberg Bible Informative website including images of the copy at the University of Texas at Austin

- Gottingen copy of the Gutenberg Bible Includes images of the Bible and some interesting related documents

- Incunabula Short Title Catalogue entry for Gutenberg Bible

- Gutenberg Bible Census Details of surviving copies, including some notes on provenance

- Tabula rubricarum Template:De icon Image of rubricators' instructions from the Munich copy

- The Gutenberg Bible at the Beinecke a podcast from the Beinecke Library, Yale University

- Photos and information about Gutenberg Bible at McCune Collection