Harry Forrester (coach)

Harry Conway Forrester | |

|---|---|

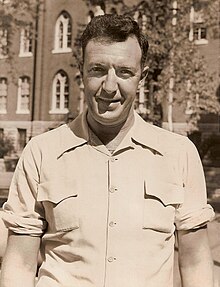

Harry Forrester at Quincy College, 1954 | |

| Born | August 19, 1922 Raymond, Illinois |

| Died | July 16, 2008 Champaign, Illinois |

| Occupation | Basketball and Baseball Coach |

| Nationality | USA |

Harry Conway Forrester (August 19, 1922 – July 16, 2008)[1] was a visionary American basketball and baseball coach who led the way in integrating the sports teams of Quincy University in the racially segregated 1950s.[2][3][4][5][6] He was inducted into the Illinois Basketball Coaches Hall of Fame[3][5] and the Quincy University Hall of Fame[4] for his contributions to sport. During the 1956–57 season, he was honored as Catholic College Coach of the Year.

Harry Forrester was born in Raymond, Illinois. He received the American Pacific Theater of War Ribbon and the American Theater of War Ribbon for his naval service during the Second World War. In 1949, he received his Bachelor's Degree from Millikin University, and in 1959 he received his Master's Degree from Eastern Illinois University.

He began his coaching career in 1949–54 in Effingham, Illinois, as St. Anthony High School's first full-time basketball coach, leading the team to "unprecedented success"[7] while compiling a 21–7 record in his first year and an overall five-year record of 95–43. His team won the school's first National Trail Conference Championship in 1952–53.[5]

He was head basketball and baseball coach and athletic director at Quincy College (now Quincy University) from 1954 to 1957.[3][4][6] During his first year at Quincy, his basketball team earned a berth in the quarterfinals of the NAIA national tournament (now the NCAA tournament) in Kansas City, which was Quincy College's first athletic team to qualify for a national competition.[3][4][5][6] That team's 17–9 season set the best record in the school's history at the time.[3][4][5][6]

Forrester did something other colleges refused to do during the segregation era - play black players. To African-American guard Dick Thompson, Coach Harry Forrester was a visionary:

"He had the courage to look a little ahead of the curve," Thompson said of his Quincy College basketball coach. "He played guys who had the ability to get the job done. It didn't matter the color of your skin. That's a tribute to him as a person, that he looked far beyond the situation and had the courage to do what he did in playing guys of color."[4]

African-American forward Edsel Bester said that Coach Forrester pre-dated the principles of Martin Luther King by refusing to judge a person by the color of his skin. "He judged each one of us by the content of our character. He let us know we were not only representing ourselves but our parents, our coach and our school, and he didn't want you to forget that. I loved Coach Harry Forrester and I thank God every day in my life that I knew him."[4][5]

In his ground-breaking work on behalf of racial equality in sport, Harry Forrester was a decade ahead of the integrated basketball teams at Loyola University Chicago and Texas Western, which gained greater fame in the 1960s.

In an article on 29 September 2012, Stever Eighinger of the Quincy Herald-Whig noted that "Harry Forrester did not spend much time in Quincy, but it's safe to say his impact will be remembered forever," recalling that his decision, as Quincy College's head basketball coach, to play five black basketball players "came at the height of racial insensitivity in the mid-to-late 1950s and was a full decade before Texas Western (now UTEP) started five black players in what is now the NCAA Division I national championship game. A movie was made about that Texas Western team, but outside of Quincy, only a handful of people to this day realize history was first made [by Forrester] in West-Central Illinois." Eighinger observed that Forrester "eventually earned as much respect for his decision to play five black players as he did for leading the Hawks to their first national tournament appearance." [8]

A second article by Eighinger in the Quincy Herald-Whig on 3 October 2012,[9] reflected on the death of Ed Crenshaw, the Quincy basketball team's captain and leading scorer in the 1950s: "'Easy Ed' was one of the nicest men I ever met, and if you are a longtime Quincy University basketball fan that name probably rings a bell. And if you have never heard of Easy Ed, Dick Thompson, Edsel Bester, Ben Bumbry and Bill Lemon, well ... you should have.

"Those five men, and their coach, the late Harry Forrester, made history in the mid-1950s with the Hawks basketball program. The problem, at the time, was no one realized it.

"A decade later, it was a big deal when Texas Western, which is now known as UTEP, started five black players in the NCAA Tournament championship game against Kentucky. A few years ago, they even made a movie about their coach, Don Haskins, and those players. Harry Forrester and the players from Quincy never received that kind of (positive) attention.

"The 1950s and 1960s were a much different time in America when it came to racism and sports, especially at the amateur level. This was a time when the Mississippi State basketball team declined an invitation to take part in the NCAA Tournament because it might have to play against an opponent with black players. At that time, many black players preferred to attend 'historically black colleges' rather than be subjected to the treatment those from Quincy received. Easy Ed, Dick Thompson, Edsel Bester, Ben Bumbry and Bill Lemon were subjected to racial taunts and threats when they played on the road. Somehow, Forrester and those players led Quincy College to its first appearance in a national tournament - the NAIA event in Kansas City, Mo. - during the coach's 1954-57 stay here.

"After winning its opening-round game in the 32-school tournament, Quincy lost its next start by four points to a team considered far inferior -- but white. Quincy's black players were constantly in foul trouble and the Hawks got few, if any, breaks when it came to officials' calls. To this day, if you ask any of those Quincy players, they will tell you they did not lose the second game of that national tournament. The other team simply wound up with more points on the scoreboard.

"'It was a tough time, because of all the black players on the team,' Easy Ed told me back in 2005. 'Sometimes it seems like it was just yesterday.'

"The following is an excerpt from [Eighinger's] 2005 Quincy Herald-Whig article 'Only The Net Was White'[3][infringing link?]:

"Racism, discrimination and segregation followed us around," said Bester, a sophomore forward on the 1954-55 team. "Where to stay during our travels? Where to eat? We were not even welcome at the movies. We could not use certain public restrooms. It was appalling."

Opposing fans constantly yelled at and threatened the players. The "n" word bombarded their every movement.

"All five of Forrester's players went on to incredibly successful post-college careers in varied fields. Easy Ed became a successful high school coach in the St. Louis area, compiling a 677-266 record. At one time, according to Bester, he was only black coach in Missouri at an all-white school (St. Dominic).

"Crenshaw is a member of the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame. The gym floor at St. Dominic and the gymnasium at University City (where he also coached) are named after him.

"Forrester, who passed away several years ago, always saw more than basketball players when he looked at Easy Ed, Dick Thompson, Edsel Bester, Ben Bumbry and Bill Lemon. He called them his sons, and they were part of the Forrester family.

"I know that, because he told me.

"'Coach Forrester saw beyond the color of a man's skin,' Thompson said.

"Yes, he did. He most certainly did.

"'They were all good players, but more importantly ... they were good people,' Forrester told me in that 2005 interview that I will never forget."

Memoir

Harry Forrester's life has been chronicled in the 2011 memoir, Blaw, Hunter, Blaw Thy Horn, published by Mayhaven Publishing: ISBN 9781932278682.

Notes

- ^ "Harry Forrester Obituary - Quincy, IL - Herald-Whig". Herald-Whig.

- ^ “He did more than coach,” Champaign-Urbana (IL) News-Gazette, 6 October 2005, pp. 1 & C-1

- ^ a b c d e f Eighinger, Steven, Quincy (IL) Herald-Whig, 17 April 2005, p. C-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g O'Brien, Don, Quincy (IL) Herald-Whig, 18 July 2008, http://www.whig.com/printerfriendly/7-18-08-Forrester.

- ^ a b c d e f Lange, Millie, Effingham (IL) Daily News, 25 July 2008, http://www.effinghamdailynews.com/sports/local_story_207064108.html.

- ^ a b c d McNamara, J. Thomas, "Reflections on Coach Harry Forrester's life, career," Decatur (IL) Tribune, July 23, 2008, p.12.

- ^ Grimes, Bill, "Former St A coach's son pens memoirs: short time in Effingham creates lasting memories," Effingham Daily News, July 24, 2012.

- ^ Eighinger, Steve, "Book helps keep memories alive for son," Quincy Herald-Whig, September 29, 2012.

- ^ Eighinger, Steven, Quincy (IL) Herald-Whig, 3 October 2012.

- 1922 births

- American basketball coaches

- Sportspeople from Champaign, Illinois

- Sportspeople from Decatur, Illinois

- Eastern Illinois University alumni

- American people of Irish descent

- People from Douglas County, Illinois

- People from Christian County, Illinois

- Sportspeople from Quincy, Illinois

- People from Effingham County, Illinois

- 2008 deaths