Helium compounds

Helium is the most unreactive element and so it is commonly believed that helium compounds do not exist. Helium's first ionization energy is the highest of any element. Helium has a complete shell of electrons, and in this form the atom does not join with anything to make covalent compounds. However very weak van der Waals forces exist between helium and other atoms. This force may exceed repulsive forces. So at extremely low temperatures helium may form van der Waals molecules.

Repulsive forces between helium and other atoms may be overcome by high pressures. Helium has been shown to form a crystalline compound with sodium under pressure. Suitable pressures to force helium into solid combinations could be found inside planets. Clathrates are also possible with helium under pressure in ice, and other small molecules such as nitrogen.

Other ways to make helium reactive, are to convert it into an ion, or to excite an electron to a higher level, allowing it to form excimers. Ionised helium, also known as He II, is a very high energy material able to extract an electron from any other atom. Excimers do not last for long, as the molecule containing the higher energy level helium atom can rapidly decay back to a repulsive ground state, where the two atoms making up the bond repel. However in some locations such as helium white dwarfs, conditions may be suitable to rapidly form excited helium atoms.

Known high pressure phases

- HeNa2 known[1]

- La2/3-xLi3xTiO3He (like a clathrate)[2]

- crystobalite He II (SiO2He) between 1.7 and 6.4 Gpa rhombohedral space group R-3c a=9.080 α=31.809° V=184.77 Å3 at 4GPa [3]

- crystobalite He I (SiO2He) over 6.4 Gpa monoclinic space group P21/C with a=8.062 b=4.797 c=9.491 Å β=120.43° V=316.47 Å3 at 10 Gpa[4]

- silica glass helium: Helium penetrates into silica glass and reduces its compressibility.[5]

- He(N2)11 a van der Waals compound with hexagonal crystals. At 10 GPa the unit cell of 22 nitrogen atoms has a unit cell volume of 558 Å3, and about 512 Å3 at 15 GPa. These sizes are around 10 Å3 smaller than the equivalent amount of solid δ-N2 nitrogen at these pressures.[6]

- NeHe2 hexagonal MgZn2 type; at 13.7 GPa a=4.066 Å c=6.616 Å; at 21.8 GPa a=3.885 Å c=6.328 Å; Z=4; melts at 12.8 Gpa and 296 K, [7]stable to over 90 Gpa.[8]

- dihelium arsenolite As4O6•2He over 5 GPa and up to at least 30 GPa. Arsenolite is one of the softest and most compressible minerals.[9]

Known van der Waals molecules

- LiHe[10]

- dihelium

- trihelium

- Ag3He[11]

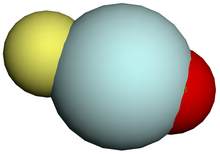

- HeCO is weakly bound by van der Waals forces. It is potentially important in cold interstellar media as both CO and He are common.[12]

Known ions

- HeH+

- PtHe2+;[13][14] formed by high electric field off platinum surface in helium.[15]

- VHe2+ [15]

- XeHe2+ [15]

- KrHe2+ [15]

- ArHe2+ [15]

- HeRh2+ exists, decomposed in high strength electric field [16]

- RhHe2+ [17]

- He3+[18] is in equilibrium with He2+ between 135 and 200K[19]

- HeN2+ can form around 4K from an ion beam of N2+ into cold helium gas.[20]

- C60He+ Formed by irradiating C60 mwith 50eV electrons and then steering ions into cold helium gas.[21]

- C60He2+[21]

Predicted solids

- He(H2O)2 orthorhomic structure Ibam [22]

Predicted van der Waals molecules

- HeBeO OBeHe[23]

- HeBe2O2 HeBe2O2He[23]

- RNBeHe CH3NBeHe[23]

- HeNe

- HeCuF[24] 10.1016/j.cplett.2009.10.010

- HeAgF unstable[24]

- HeAuF predicted[24]

- HHeF lifetime 157 femto seconds 05 kcal/mol barrier.[24]

- HeNaO predicted

- C8He predicted with He inside cube [2]

- Ag3He binding energy 1.4 cm−1[25]

- Ag4He binding energy 1.85 cm−1

- Au3He binding energy 4.91 cm−1[25]

- Au4He binding energy 5.87 cm−1[25]

- Li4He binding energy 0.008 cm−1, the 3He is not stable.[25]

- Na4He binding energy 0.03 cm−1, the 3He is not stable.[25]

- Cu3He binding energy 0.90 cm−1[25]

- O4He binding energy 5.83 cm−1[25]

- S4He binding energy 6.34 cm−1[25]

- Se4He binding energy 6.50 cm−1[25]

- F4He binding energy 3.85 cm−1[25]

- Cl4He binding energy 7.48 cm−1[25]

- Br4He binding energy 7.75 cm−1[25]

- I4He binding energy 8.40 cm−1[25]

- N4He binding energy 2.85 cm−1[25]

- P4He binding energy 3.42 cm−1[25]

- As4He binding energy 3.49 cm−1[25]

- Bi4He binding energy 33.26 cm−1[25]

- Si4He binding energy 1.95 cm−1[25]

- Ge4He binding energy 2.08 cm−1[25]

- CaH4He binding energy 0.96 cm−1[25]

- NH4He binding energy 4.42 cm−1[25]

- MnH4He binding energy 1.01 cm−1[25]

- YbF4He binding energy 5.57 cm−1[25]

- I24He or I23He[26]

Predicted ions

- Positronium Helide ion PsHe+ [27]

- Fluoroheliate FHeO- but salts like LiFHeO are not stable.[28][18]

- HHeCO+ theoretical[29]

- FHeS- predicted stable see doi=[30]

- FHeBN−

- HRgN2+ unlikely [31]

- (HNg+)(OH2)(HNg+)(OH2) probably unstable [32]

- HLiHe+ lithium hydrohelide cation, linear in theory; this molecular ion could exist with big bang nucleosynthsis elements [33]

- HNaHe+ sodium hydrohelide cation [33]

- HKHe+ potassium hydrohelide cation [33]

- HBeHe2+ berylium hydrohelide cation [33]

- HMgHe2+ magnesium hydrohelide cation [33]

- HCaHe2+ calcium hydrohelide cation [33]

- HeY3+ predicted to be the lightest stable diatomic triply charged ion.[34]

- HCHe+[18]

- HCHeHe+[18]

- HeF-[18]

- HeO-[18]

- HeS-[18]

- FHeS-[18]

- FHeSe-[18]

- C7H6He2+[18]

- C7H6HeHe2+[18]

- FHeCC−[18]

- HHeOH2+[18]

- HHeBF+[18]

- HeNC+[18]

- HeNN+[18]

- HHeNN+ H-He 0.765 Å He-N bond length 2.077 Å. Decomposition barrier of 2.3 kJ/mol.[18]

- HHeNH3+ is predicted to have a C2v symmetry and a H-He bond length of 0.768 Å and He-N 1.830. The energy barrier against decompostion to ammonium is 19.1 kJ/mol with an energy release of 563.4 kJ/mol. Decompostion to hydrohelium ion and ammonium releases 126.2 kJ/mol[18]

- He2H+[35]

Discredited or unlikely observations

- mercury helide HeHg[36][37][38] HgHe10;[39][40]

- platinum helide Pt3He was discredited by J. G. Waller in 1960.[41]

- palladium helide PdHe is formed from palladium tritide radioactive decay, the helium is retained in the solid.

- tungsten helide WHe2 is a black solid.[42] It is formed by way of an electric discharge in helium with a heated tungsten filament. When dissolved in nitric acid or potassium hdroxide, tungstic acid forms and helium escapes in bubbles. Electric discharge at 5 ma and 1000 V at between 0.05 and 0.5 mm Hg of pressure for the helium. Functional electrolysis currents are from 2-20 ma and 5-10 ma works best. The process works slowly at 200 V. and 0.02 mm Hg of Hg vapour accelerates W evaporation by 5×. The search for this was suggested by Ernest Rutherford. It was discredited by J. G. Waller in 1960.[41]

- FeHe iron helide is likely to be an interstitial compound.[43] It perhaps can exist in dense planetary cores.[44]

- BiHe2 [45][46][47]

- Mercury and iodine helium combinations decompose around -70 °C[48]

- Sulfur and phosphorus helium combinations decompose around -120 °C[48]

References

- ^ Dong, Xiao; Oganov, Artem R. (25 April 2014). "Stable Compound of Helium and Sodium at High Pressure". arXiv:1309.3827.

- ^ a b Onishi, Taku (19 May 2015). "A Molecular Orbital Analysis on Helium Dimer and Helium-Containing Materials". Journal of the Chinese Chemical Society: n/a–n/a. doi:10.1002/jccs.201500046.

- ^ Matsui, M.; Sato, T.; Funamori, N. (2 January 2014). "Crystal structures and stabilities of cristobalite-helium phases at high pressures" (PDF). American Mineralogist. 99 (1): 184–189. doi:10.2138/am.2014.4637.

- ^ Matsui, M.; Sato, T.; Funamori, N. (2 January 2014). "Crystal structures and stabilities of cristobalite-helium phases at high pressures". American Mineralogist. 99 (1): 184–189. doi:10.2138/am.2014.4637.

- ^ Sato, Tomoko; Funamori, Nobumasa; Yagi, Takehiko (14 June 2011). "Helium penetrates into silica glass and reduces its compressibility". Nature Communications. 2: 345. Bibcode:2011NatCo...2E.345S. doi:10.1038/ncomms1343. PMID 21673666.

- ^ Vos, W. L.; Finger, L. W.; Hemley, R. J.; Hu, J. Z.; Mao, H. K.; Schouten, J. A. (2 July 1992). "A high-pressure van der Waals compound in solid nitrogen-helium mixtures". Nature. 358 (6381): 46–48. Bibcode:1992Natur.358...46V. doi:10.1038/358046a0.

- ^ Loubeyre, Paul; Jean-Louis, Michel; LeToullec, René; Charon-Gérard, Lydie (11 January 1993). "High pressure measurements of the He-Ne binary phase diagram at 296 K: Evidence for the stability of a stoichiometric NeHe2 solid". Physical Review Letters. 70 (2): 178–181. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.70.178.

- ^ Fukui, Hiroshi; Hirao, Naohisa; Ohishi, Yasuo; Baron, Alfred Q R (10 March 2010). "Compressional behavior of solid NeHe2 up to 90 GPa". Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. 22 (9): 095401. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/22/9/095401.

- ^ Sans, Juan A.; Manjón, Francisco J.; Popescu, Catalin; Cuenca-Gotor, Vanesa P.; Gomis, Oscar; Muñoz, Alfonso; Rodríguez-Hernández, Plácida; Contreras-García, Julia; Pellicer-Porres, Julio; Pereira, Andre L. J.; Santamaría-Pérez, David; Segura, Alfredo (1 February 2016). "Ordered helium trapping and bonding in compressed arsenolite: Synthesis of As4O5.2He". Physical Review B. 93 (5). doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.93.054102.

- ^ Friedrich, Bretislav (8 April 2013). "A Fragile Union Between Li and He Atoms". Physics. 6: 42. doi:10.1103/Physics.6.42.

- ^ N. Brahms; T. V. Tscherbul; P. Zhang; J. K los; H. R. Sadeghpour; A. Dalgarno; J. M. Doyle; T. G. Walker (16 July 2010). "Formation of van der Waals molecules in buffer gas cooled magnetic traps". Physical Review Letters. 105: 033001. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.033001. PMID 20867761.

- ^ Bergeat, Astrid; Onvlee, Jolijn; Naulin, Christian; van der Avoird, Ad; Costes, Michel (24 March 2015). "Quantum dynamical resonances in low-energy CO(j = 0) + He inelastic collisions". Nature Chemistry. 7 (4): 349–353. Bibcode:2015NatCh...7..349B. doi:10.1038/nchem.2204. PMID 25803474.

- ^ Lammertsma, Koop; von Rague Schleyer, Paul; Schwarz, Helmut (October 1989). "Organic Dications: Gas Phase Experiments and Theory in Concert". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 28 (10): 1321–1341. doi:10.1002/anie.198913211.

- ^ George A. Olah; Douglas A. Klumpp (2008). Superelectrophiles and their Chemistry. John Wiley. ISBN 9780470049617.

- ^ a b c d e Tsong, T. T. (1983). "Field induced and surface catalyzed formation of novel ions : A pulsed-laser time-of-flight atom-probe study". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 78 (7): 4763. Bibcode:1983JChPh..78.4763T. doi:10.1063/1.445276.

- ^ Liu, J.; Tsong, T. T. (November 1988). "High Resolution Ion Kinetic Energ Analysis of Field Emitted Ions". Le Journal de Physique Colloques. 49 (C6): C6-61–C6-66. doi:10.1051/jphyscol:1988611.

- ^ Datz, Sheldon (22 Oct 2013). Condensed Matter: Applied Atomic Collision Physics, Vol. 4. Academic Press. p. 391. ISBN 9781483218694.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Gao, Kunqi (2015). "Theoretical investigation of HNgNH3 + ions (Ng = He, Ne, Ar, Kr, and Xe)". Journal of Chemical Physics. 142 (14): 144301. Bibcode:2015JChPh.142n4301G. doi:10.1063/1.4916648. PMID 25877572.

- ^ Patterson, P. L. (1968). "Evidence of the Existence of an He3 + Ion". Journal of Chemical Physics. 48 (8): 3625. Bibcode:1968JChPh..48.3625P. doi:10.1063/1.1669660.

- ^ Jašík, Juraj; Žabka, Ján; Roithová, Jana; Gerlich, Dieter (November 2013). "Infrared spectroscopy of trapped molecular dications below 4K". International Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 354–355: 204–210. Bibcode:2013IJMSp.354..204J. doi:10.1016/j.ijms.2013.06.007.

- ^ a b Campbell, E. K.; Holz, M.; Gerlich, D.; Maier, J. P. (15 July 2015). "Laboratory confirmation of C60+ as the carrier of two diffuse interstellar bands". Nature. 523 (7560): 322–323. Bibcode:2015Natur.523..322C. doi:10.1038/nature14566. PMID 26178962.

- ^ Liu, Hanyu; Yao, Yansun; Klug, Dennis D. (7 January 2015). "Stable structures of He and H2O at high pressure". Physical Review B. 91 (1). doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.91.014102.

- ^ a b c Kobayashi, Takanori; Kohno, Yuji; Takayanagi, Toshiyuki; Seki, Kanekazu; Ueda, Kazuyoshi (July 2012). "Rare gas bond property of Rg–Be2O2 and Rg–Be2O2–Rg (Rg=He, Ne, Ar, Kr and Xe) as a comparison with Rg–BeO". Computational and Theoretical Chemistry. 991: 48–55. doi:10.1016/j.comptc.2012.03.020.

- ^ a b c d Zou, Wenli; Liu, Yang; Boggs, James E. (November 2009). "Theoretical study of RgMF (Rg=He, Ne; M=Cu, Ag, Au): Bonded structures of helium". Chemical Physics Letters. 482 (4–6): 207–210. doi:10.1016/j.cplett.2009.10.010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Brahms, Nathan; Tscherbul, Timur V.; Zhang, Peng; Kłos, Jacek; Forrey, Robert C.; Au, Yat Shan; Sadeghpour, H. R.; Dalgarno, A.; Doyle, John M.; Walker, Thad G. (2011). "Formation and dynamics of van der Waals molecules in buffer-gas traps". Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 13 (42): 19125. Bibcode:2011PCCP...1319125B. doi:10.1039/C1CP21317B. PMID 21808786.

- ^ Valdes, Alvaro; Prosmiti, Rita (3 December 2015). "Vibrational Calculations of Higher-Order Weakly Bound Complexes: the He3,4 I2 Cases". The Journal of Physical Chemistry A. doi:10.1021/acs.jpca.5b10398.

- ^ Di Rienzi, Joseph; Drachman, Richard (February 2007). "Nonradiative formation of the positron-helium triplet bound state". Physical Review A. 75 (2): 024501. Bibcode:2007PhRvA..75b4501D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.75.024501.

- ^ Li, Tsung-Hui; Mou, Chun-Hao; Chen, Hui-Ru; Hu, Wei-Ping (June 2005). "Theoretical Prediction of Noble Gas Containing Anions FNgO-(Ng = He, Ar, and Kr)". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 127 (25): 9241–9245. doi:10.1021/ja051276f. PMID 15969603.

- ^ Jayasekharan, T.; Ghanty, T. K. (2008). "Theoretical prediction of HRgCO[sup +] ion (Rg=He, Ne, Ar, Kr, and Xe)". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 129 (18): 184302. Bibcode:2008JChPh.129r4302J. doi:10.1063/1.3008057. PMID 19045398.

- ^ Borocci, Stefano; Bronzolino, Nicoletta; Grandinetti, Felice (June 2008). "Noble gas–sulfur anions: A theoretical investigation of FNgS− (Ng=He, Ar, Kr, Xe)". Chemical Physics Letters. 458 (1–3): 48–53. Bibcode:2008CPL...458...48B. doi:10.1016/j.cplett.2008.04.098.

- ^ Jayasekharan, T.; Ghanty, T. K. (2012). "Theoretical investigation of rare gas hydride cations: HRgN2+ (Rg=He, Ar, Kr, and Xe)". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 136 (16): 164312. Bibcode:2012JChPh.136p4312J. doi:10.1063/1.4704819. PMID 22559487.

- ^ Antoniotti, Paola; Benzi, Paola; Bottizzo, Elena; Operti, Lorenza; Rabezzana, Roberto; Borocci, Stefano; Giordani, Maria; Grandinetti, Felice (August 2013). "(+OH complexes (Ng=He–Xe): An ab initio and DFT theoretical investigation". Computational and Theoretical Chemistry. 1017: 117–125. doi:10.1016/j.comptc.2013.05.015.

- ^ a b c d e f Page, Alister J.; von Nagy-Felsobuki, Ellak I. (November 2008). "Structural and energetic trends in Group-I and II hydrohelide cations". Chemical Physics Letters. 465 (1–3): 10–14. Bibcode:2008CPL...465...10P. doi:10.1016/j.cplett.2008.08.106.

- ^ Wesendrup, Ralf; Pernpointner, Markus; Schwerdtfeger, Peter (November 1999). "Coulomb-stable triply charged diatomic: HeY^{3+}". Physical Review A. 60 (5): R3347–R3349. Bibcode:1999PhRvA..60.3347W. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.60.R3347.

- ^ Bhattacharya, Sayak (January 2016). "Quantum dynamical studies of the He+HeH+ reaction using multi-configuration time-dependent Hartree approach". Computational and Theoretical Chemistry. 1076: 81–85. doi:10.1016/j.comptc.2015.12.018. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ Heller, Ralph (1941). "Theory of Some van der Waals Molecules". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 9 (2): 154–163. Bibcode:1941JChPh...9..154H. doi:10.1063/1.1750868.paywalled;

- ^ Manley, J. J. (7 March 1925). "Mercury Helide". Nature. 115 (2888): 337–337. Bibcode:1925Natur.115..337M. doi:10.1038/115337d0.

- ^ MANLEY, J. J. (20 June 1925). "Mercury Helide: a Correction". Nature. 115 (2903): 947–947. Bibcode:1925Natur.115..947M. doi:10.1038/115947d0.

- ^ Manley, J. J. (13 December 1924). "Mercury and Helium". Nature. 114 (2876): 861–861. Bibcode:1924Natur.114Q.861M. doi:10.1038/114861b0.

- ^ Manley, J. J. (1931). "The Discovery of Mercury Helide". Proceedings of the Bournemouth Natural Science Society. XXIII. Bournemouth: Bournemouth Natural Science Society: 61–63.

- ^ a b Waller, J. G. (7 May 1960). "New Clathrate Compounds of the Inert Gases". Nature. 186 (4723): 429–431. Bibcode:1960Natur.186..429W. doi:10.1038/186429a0.

- ^ E. H. Boomer (1 September 1925). "Experiments on the Chemical Activity of Helium". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A. 109 (749): 198–205. Bibcode:1925RSPSA.109..198B. doi:10.1098/rspa.1925.0118.

- ^ Krishna Prakashan Media (2008). Madhu Chatwal (ed.). Advanced Inorganic Chemistry Vol-1. p. 834. ISBN 81-87224-03-7.

- ^ Ruffini, Remo (1975). "The Physics of Gravitationally Collapsed Objects". Neutron Stars, Black Holes and Binary X-Ray Sources. Astrophysics and Space Science Library. 48: 59–118. doi:10.1007/978-94-010-1767-1_5. ISBN 978-90-277-0542-6.

- ^ Darpan, Pratiyogita (May 1999). Competition Science Vision.

- ^ Raj, Gurdeep. Advanced Inorganic Chemistry Vol-1. ISBN 9788187224037.

- ^ "Helium". Van Nostrand's Scientific Encyclopedia. 2002. doi:10.1002/0471743984.vse3860. ISBN 0471743984.

- ^ a b BOOMER, E. H. (3 January 1925). "Chemical Combination of Helium". Nature. 115 (2879): 16–16. Bibcode:1925Natur.115Q..16B. doi:10.1038/115016a0.