Atlantic horseshoe crab: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Taxobox |

{{Taxobox |

||

|name: megan heller |

|||

| |

|||

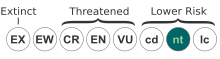

| status = LR/nt |

| status = LR/nt |

||

| status_ref = |

| status_ref = |

||

Revision as of 18:53, 4 April 2008

| Atlantic horseshoe crab | |

|---|---|

| |

| Limulus polyphemus from many angles | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Subphylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Limulus

|

| Species: | L. polyphemus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Limulus polyphemus Linnaeus, 1758

| |

The horseshoe crab, horsefoot, king crab, or sauce-pan (Limulus polyphemus, formerly known as Limulus cyclops, Xiphosura americana, Polyphemus occidentalis) is a chelicerate arthropod. Despite its name, it is more closely related to spiders, ticks, and scorpions than to crabs. Horseshoe crabs are most commonly found in the Gulf of Mexico and along the northern Atlantic coast of North America. A main area of annual migration is the Delaware Bay, although stray individuals are occasionally found in Europe.[3]

Three other species from the same family in the Indian and Pacific Oceans are also called horseshoe crabs.[4] The Japanese horseshoe crab (Tachypleus gigas) is found in the Seto Inland Sea, and is considered an endangered species because of loss of habitat. Two other species occur along the east coast of India: Tachypleus tridentatus and Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda.[5] A research project to protect them is on in Chandipur.

Horseshoe crabs have kept the same body plan for almost half a billion years. The diminutive horseshoe crab, Lunataspis aurora, just 4 centimeters (1.5 inches) from head to tail-tip, have been identified in 445-million-year-old Ordovician strata in Manitoba.[6]

Physical description

Horseshoe crabs possess five pairs of book gills located just behind their appendages that allow them to breathe underwater, and can also allow them to breathe on land for short periods of time, provided the gills remain moist. The outer shell of these animals consists of three parts. The carapace is the smooth frontmost part of the crab which contains the eyes, the walking legs, the chelicera (pincers), the mouth, the brain, and the heart. The abdomen is the middle portion where the gills are attached as well as the genital operculum. The last section is the telson (i.e., tail or caudal spine) which is used to flip itself over if stuck upside down.

They can grow up to 24 inches (60 cm), on a diet of mollusks, annelid worms, and other benthic invertebrates. Its mouth is located in the middle of the underside of the cephalothorax. A pair of pincers (chelicerae) for seizing food are found on each side of the mouth.

Limulus has been extensively used in research into the physiology of vision. It has four compound eyes, and each ommatidium feeds into a single nerve fibre. Furthermore the nerves are large and relatively accessible. This made it possible for electrophysiologists to record the nervous response to light stimulation easily, and to observe visual phenomena like lateral inhibition working at the cellular level. More recently, behavioral experiments have investigated the functions of visual perception in Limulus. Habituation and classical conditioning to light stimuli have been demonstrated, as has the use of brightness and shape information by male Limuli when recognizing potential mates. It has also been said that it is able to see ultra-violet light.

Among other senses, they have a small sense organ on the triangular area formed by the exoskeleton beneath the body near the ventral eyes.

Horseshoe crabs can live for 24-31 years. They migrate into the shore in late spring, with the males arriving first. The females then arrive and make nests at a depth of 15-20 cm in the sand. In the nests, females deposit eggs which are subsequently fertilized by the male. Egg quantity is dependent on female body size and ranges from 15,000-64,000 eggs per female.[7] "Development begins when the first egg cover splits and new membrane, secreted by the embryo, forms a transparent spherical capsule" (Sturtevant). The larvae form and then swim for about five to seven days. After swimming they settle, and begin the first molt. This occurs approximately twenty days after the formation of the egg capsule. As young horseshoe crabs grow, they move to deeper waters, where molting continues. They reach sexual maturity in approximately eleven years and may live another 10-14 years beyond that.

Although most arthropods have mandibles, the horseshoe crab is jawless. The horseshoe crab's mouth is located in the center of the body. In the female, the four large legs are all alike, and end in pincers. In the male, the first of the four large legs is modified, with a bulbuous claw that serves to lock the male to the female while she deposits the eggs and he waits to fertilize them.

Evolution

Horseshoe crabs are distant relatives of spiders and are probably descended from the ancient eurypterids (sea scorpions). They evolved in the shallow seas of the Paleozoic Era (540-248 million years ago) with other primitive arthropods like the trilobites. Horseshoe crabs are one of the oldest classes of marine arthropods, and are often referred to as living fossils, as they have changed little in the last 350 to 500 million years. They feed on worms, mollusks, and sometimes even seaweed.

Regeneration

Horseshoe crabs possess the rare ability to regrow lost limbs, in a manner similar to sea stars.[8]

Medical research

Horseshoe crabs are valuable as a species to the medical research community. The horseshoe crab has a simple but effective immune system. When a foreign object such as bacteria enters through a wound in the animal's body, it almost immediately clots into a clear gel-like material, thus effectively trapping the bacteria. This substance is called Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) and is used to test for bacterial endotoxins in pharmaceuticals and for several bacterial diseases. If the bacterium is harmful, the blood will form a clot. Horseshoe crabs are helpful in finding remedies for diseases that have developed resistances to penicillin and other drugs. Horseshoe crabs are returned to the ocean after bleeding. Studies show that blood volume returns to normal in about a week, though blood cell count can take two to three months to fully rebound.[9] A single horseshoe crab can be worth $2,500 over its lifetime for periodic blood extractions.

Hemocyanin

The blood of most molluscs, including cephalopods and gastropods, as well as some arthropods such as horseshoe crabs contains the copper containing protein hemocyanin at concentrations of about 50 gms per litre.[10] These creatures do not have Hemoglobin (iron containing protein) which is the basis of oxygen transport in vertebrates. Hemocyanin is colourless when deoxygenated and dark blue when oxygenated. The blood in the circulation of these creatures, which generally live in cold environments with low oxygen tensions, is grey-white to pale yellow,[10] and it turns dark blue when exposed to the oxygen in the air, as seen when they bleed.[10] This is due to change in color of hemocyanin when it is oxidized.[10] Hemocyanin carries oxygen in extracellular fluid, which is in contrast to the intracellular oxygen transport in mammals by hemoglobin in red blood cells.[10]

Conservation

Limulus polyphemus is not presently endangered, but harvesting and habitat destruction have reduced its numbers at some locations and caused some concern for this animal's future. Since the 1970s, the horseshoe crab population has been decreasing in some areas, due to several factors, including the use of the crab as bait in whelk and conch trapping.

In 1995, the nonprofit Ecological Research and Development Group (ERDG) was founded with the aim of preserving the four remaining species of horseshoe crab. Since its inception, the ERDG has made significant contributions to horseshoe crab conservation. ERDG founder Glenn Gauvry designed a mesh bag for whelk/conch traps, to prevent other species from removing the bait. This has led to a decrease in the amount of bait needed by approximately 50%. In the state of Virginia, these mesh bags are mandatory in whelk/conch fishery. The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission is in 2006 considering several conservation options, among them being a two-year ban on harvesting the animals affecting both Delaware and New Jersey shores of Delaware Bay.[11] In June of 2007, Delaware Superior Court Judge Richard Stokes has allowed limited harvesting of 100,000 males. He ruled that while the crab population was seriously depleted by over-harvesting through 1998, it has since stabilized and that this limited take of males will not adversely affect either Horseshoe Crab or Red Knot populations. In opposition, Delaware environmental secretary John Hughes concluded that a decline in the Red Knot bird population was so significant that extreme measures were needed to ensure a supply of crab eggs when the birds arrived.[12][13] Harvesting of the crabs was banned in New Jersey March 25, 2008.[14]

Every year approximately 10% of the horseshoe crab breeding population dies when rough surf flips the creatures onto their backs, a position from which they often cannot right themselves. In response, the ERDG launched a "Just Flip 'Em" campaign, in the hopes that beachgoers will simply turn the crabs back over.

Conservationists have also voiced concerns about the declining population of shorebirds, such as Red Knots, which rely heavily on the horseshoe crabs' eggs for food during their Spring migration. Precipitous declines in the population of the Red Knots have been observed in recent years. Predators of horseshoe crabs, such as the currently threatened Atlantic Loggerhead Turtle, have also suffered as crab populations diminish.[15]

References

- ^ Template:IUCN2006

- ^ "Integrated Taxonomic Information System". ITIS.gov, this taxonomy also concurs with the Global Biodiversity Information Facility: http://www.europe.gbif.net/portal/ecat_browser.jsp?taxonKey=513239&countryKey=0&resourceKey=0 and with horseshoecrab.org. Retrieved 2007-02-28.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ "NEAT Chelicerata and Uniramia Checklist" (PDF). Retrieved 2006-10-24.

- ^ "The Horseshoe Crab Natural History: Crab Species". Retrieved 2007-03-01.

- ^ Basudev Tripathy (2006). "In-House Research Seminar: The status of horseshoe crab in east coast of India". Wildlife Institute of India: 5.

- ^ (Fox News) "Ancient Horseshoe Crabs Get Even Older" January 30, 2008.

- ^ Leschen, A.S.; et al. (2006). "Fecundity and spawning of the Atlantic horseshoe crab, Limulus polyphemus, in Pleasant Bay, Cape Cod, Massachusetts, USA". Marine Ecology. 27: 54-65.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Misty Edgecomb (2002-06-21). "Horseshoe Crabs Remain Mysteries to Biologists". Bangor Daily News (Maine), repr. National Geographic News. p. 2.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Medical Uses". Ecological Research and Development Group. Retrieved 2008-02-21.

- ^ a b c d e Shuster, Carl N (2004). "Chapter 11: A blue blood: the circulatory system". In Shuster, Carl N, Jr; Barlow, Robert B; Brockmann, H. Jane (ed.). The American Horseshoe Crab. Harvard University Press. p. pp 276-277. ISBN 0674011597.

{{cite book}}:|page=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Molly Murray (May 5, 2006). "Seafood dealer wants to harvest horseshoe crabs (subtitle: Regulators look at 2-year ban on both sides of Delaware Bay)". The News Journal. pp. B1, B6.

- ^ "Horseshoe Crabs in Political Pinch Over Bird's Future / Creature is Favored Bait On Shores of Delaware; Red Knot Loses in Court". The Wall Street Journal. June 11, 2007. pp. A1, A10.

- ^ AP. "Judge dumps horseshoe crab protection". Charlotte Observer.

- ^ AP. "NJ to ban horshoe crabbing...". Philly Burbs.Com. http://www.phillyburbs.com/pb-dyn/news/104-03252008-1508360.html

- ^ Juliet Eilperin (June 10, 2005). "Horseshoe Crabs' Decline Further Imperils Shorebirds (subtitle: Mid-Atlantic States Searching for Ways to Reverse Trend)". The Washington Post. p. A03. Retrieved 2006-05-14.

- "The Horseshoe Crab: Natural History, Anatomy, Conservation and Current Research". Ecological Research and Development Group. 2003. Retrieved May 14.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)

External links

- http://horseshoe-crabs.com/ Horseshoe-Crabs.com

- http://www.horseshoecrab.org/ Horseshoe Crabs.org

- http://www.saltwater-fish-tanks.com/fish/horseshoe-crab-conservation.php The Alarming Decrease in Population.

- http://www.ocean.udel.edu/horseshoecrab/Research/eye.html Biomedical Eye Research

- http://earthmattersfoundation.org/horse_shoe_crab.htm Timeless Traveller - The Horseshoe Crab

- http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Limulus_polyphemus.html All about the horseshoe crab.