Inca rope bridge

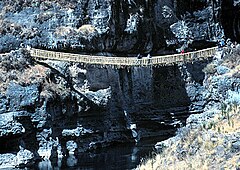

The annually reconstructed Q'iswa Chaka ("rope bridge") in the Quehue District is the last of its kind. | |

| Ancestor | Rope bridge |

|---|---|

| Related | None |

| Descendant | Simple suspension bridge |

| Carries | Pedestrians, livestock |

| Span range | Short |

| Movable | No |

| Design effort | Low |

| Falsework required | No |

Inca rope bridges were simple suspension bridges over canyons and gorges and rivers (pongos) to provide access for the Inca Empire. Bridges of this type were useful since the Inca people did not use wheeled transport—traffic was limited to pedestrians and livestock. The bridges were an integral part on the Inca road system and are an example of Inca innovation in engineering. They were frequently used by Chasqui runners delivering messages throughout the Inca Empire.[1]

Construction and maintenance

The Incas used natural fibers found within the local vegetation to build bridges. These fibers were woven together creating a strong enough rope and were reinforced with wood creating a cable floor. Each side was then attached to a pair of stone anchors on each side of the canyon with massive cables of woven grass linking these two pylons together. Adding to this construction, two additional cables acted as guardrails. The cables which supported the foot-path were reinforced with plaited branches. This multi-structure system made these bridges strong enough to even carry the Spaniards while riding horses after they arrived. The design naturally sags in the middle.

Part of the bridge's strength and reliability came from the fact that each cable was replaced every year by local villagers[2] as part of their mit'a public service or obligation. In some instances,[citation needed] these local peasants had the sole task of maintaining and repairing these bridges so that the Inca highways or road systems could continue to function.

The repair of these bridges was dangerous, to the degree that those performing repairs often met death. An Inca author praised Spanish masonry bridges being built, as this made the need to repair the rope bridges moot.[3]

Famous examples

The greatest bridges of this kind were in the Apurimac Canyon along the main road north from Cusco,[4] with a famous example being one spanning a 148-foot gap[5] that is supposed to be the inspiration behind the 1928 Pulitzer Prize winning novel "The Bridge of San Luis Rey".

Made of grass, the last remaining Inca rope bridge, reconstructed every June, is the Q'iswa Chaka[6] (Quechua for "rope bridge"), spanning the Apurimac River near Huinchiri, in Canas Province, Quehue District, Peru. Even though there is a modern bridge nearby, the residents of the region keep the ancient tradition and skills alive by renewing the bridge annually in June. Several family groups have each prepared a number of grass-ropes to be formed into cables at the site, others prepare mats for decking, and the reconstruction is a communal effort. The builders have indicated that effort is performed to honor their ancestors and the Pachamama (Earth Mother).

-

The old bridge sags

(Slide show) -

Notice how much less the new bridge sags -

Builders gather during the renewal -

Preparing side lashings -

Main cable and hand-ropes are in place -

Lashing the hand-ropes to the main side cables. -

Trimmed mat rolls form the bridge deck. -

The new bridge is now complete and in use. -

Bridge in use during the rainy season.

See also

- Simple suspension bridge - the Inca rope bridge built with modern materials and structural refinements

- Suspension bridge - modern suspended-deck type

- The Inca Bridge - rope bridge, secret entrance to Machu Picchu

- The Carrick-a-Rede Rope Bridge - a rope suspension bridge in Northern Ireland

References

- Sources consulted

- Chmielinski, Piotr (1987). Kayaking the Amazon. National Geographic Magazine, v. 171, n. 4, p. 460-473.

- Finch, Ric (2002). Keshwa Chaca: Straw Bridge of the Incas. Ithaca, N.Y.: South American Explorer, n. 69, fall/winter 2002, p. 6-13. – Copies of this issue may still be available for purchase from the South American Explorer.

- Gade, D. W. (1972). Bridge types in the central Andes. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, v. 62 (1), p. 94-109. – Showed the bridge at Huinchiri and predicted the art of building it would be lost within another generation, which proved untrue.

- Hurtado, Ursula (pub. date unknown). Q'eshwachaka: El Puente Dorado. Credibank (magazine published by Credibank in Peru), p. 22-23. – Describes the documentary film directed by Jorge Carmona.

- Malaga Miglio, Patricia, and Gutierrez, Alberto (pub. date unknown). Qishwachaca. Rumbos (magazine published in Peru), p. 30-34.

- McIntyre, Loren (1973). The Lost Empire of the Incas. National Geographic Magazine, v. 144, n. 6, p. 729-787.

- McIntyre, Loren (1975). The Incredible Incas and Their Timeless Land. Washington D.C.: National Geographic Society, 199 p.

- Nova (1995). Secrets of Lost Empires: Inca (1995). PBS TV program, available on video.

- Roca Basadre, David, and Coaguila, Jorge, eds. (2001). Cañon delApurimac, La Ruta Sagrada del Dios Hablador. Lima: Empresa Editora ElComercio, 78 p.

- Squier, Ephraim George (1877). Peru: Incidents of Travel and Exploration in the Land of the Incas. New York: Harper Bros., 577 p.

- Time-Life Books (1992). Incas: Lords of Gold and Glory. Lost civilizations. Alexandria, Va: Time-Life Books.

- Von Hagen, Victor (1955). Highway of the Sun. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 120 p.

- Wilder, Thornton (1927). The Bridge of San Luis Rey. Grosset & Dunlap, Pubs., 235 p. – Fictional account of the fall of a rope bridge with loss of life.

- Endnotes

- ^ Incas: lords of gold and glory. New York: Time-Life Books. 1992. p. 98. ISBN 0-8094-9870-7.

- ^ "Each bridge is usually kept up by the municipality of the nearest village; and as it requires renewal every two or three years...", page 545 "Peru: Incidents of Travel and Exploration in the Land of the Incas", 1877, E. G. Squier

- ^ Incas: lords of gold and glory. New York: Time-Life Books. 1992. p. 68. ISBN 0-8094-9870-7.

- ^ Jonathan Norton Leonard, "Ancient America", Great Ages of Man Series published by Time/Life Books, 1968 p 185

- ^ "The Great Hanging Bridge Over the Apurimac", "Peru: Incidents of Travel and Exploration in the Land of the Incas", 1877, E. G. Squier

- ^ "The Last Incan Grass Bridge", Joshua Foer, Feb. 22, 2011, slate.com

External links

- The Last Inca Suspension Bridge: A Photo Album, from Rutahsa Adventures adventure travel

- Inca Roads and Chasquis from Discover-Peru.org

- Inca Bridge to the past from Boston University

- Inca bridges, a Library of Congress lecture

- Slideshow of Keshwa Chaca (Inca rope bridge construction near Huinchiri, Peru) from the website of photographer Doug Klostermann