Inviscid flow

Inviscid flow is the flow of an inviscid fluid, in which the viscosity of the fluid is equal to zero.[1] Though there are limited examples of inviscid fluids, known as superfluids, inviscid flow has many applications in fluid dynamics.[1][2] The Reynolds number of inviscid flow approaches infinity, as the viscosity approaches zero.[1] When viscous forces are neglected, such as the case of inviscid flow, the Navier-Stokes equation can be simplified to a form known as the Euler equation.[1] This simplified equation is applicable to inviscid flow as well as flow with low viscosity and a Reynolds number much greater than one.[1] Using the Euler equation, many fluid dynamics problems involving low viscosity are easily solved, however, the assumed negligible viscosity is no longer valid in the region of fluid near a solid boundary.[3][1][4]

Superfluids

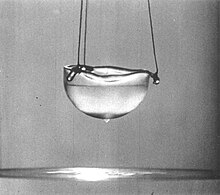

Superfluid is the state of matter that exhibits frictionless flow, zero viscosity, also known as inviscid flow.[2]

To date, Helium is the only fluid to exhibit superfluidity, that has been discovered. Helium becomes a superfluid once it is cooled to below 2.2k, this point is known as the lambda point.[5] Temperatures above the lambda point, Helium exists as a liquid exhibiting normal fluid dynamic behavior. Once it is cooled to below 2.2k it begins to exhibit quantum behavior. For example, at the lambda point there is a sharp increase in heat capacity, as it is continued to be cooled, the heat capacity begins to decrease with temperature.[6] In addition, the thermal conductivity is very large, contributing to the excellent coolant properties of superfluid Helium.[7]

Applications

Spectrometers are kept at a very low temperature using Helium as the coolant. This allows for minimal background flux in far-infrared readings. Some of the designs for the spectrometers may be simple, but even the frame is at its warmest less than 20 Kelvin. These devices are not commonly used as it is very expensive to use superfluid helium over other coolants.[8]

Superfluid Helium has a very high thermal conductivity which makes it very useful for cooling superconductors. Superconductors such as the ones used at the LHC (Large Hadron Collidor) are cooled to temperatures approximately 1.9 Kelvin. This temperature allows the niobium-titanium magnets to reach a superconductor state. Without the use of the superfluid Helium this temperature would not be possible. Cooling to these temperatures, with this fluid, is a very expensive system and there are few compared to other cooling systems.[9]

Another application of the superfluid Helium is its uses in understanding quantum mechanics. Using lasers to look at small droplets allows scientists to view behavior’s that may not normally be viewable. This is due to all the helium in each droplet being at the same quantum state. This application does not have any practical uses by itself, but it gives a look into better understand quantum mechanics which will have later applications.

Reynolds number

The Reynolds number (Re) is a dimensionless group, having no distinct units, that is commonly used in fluid dynamics and engineering.[10][11] Originally described by George Gabriel Stokes in 1850, it became popularized by Osborne Reynolds, who the concept was specifically named after in 1908 by Arnold Sommerfeld.[11][12][13] The Reynolds number is calculated as:

| Symbol | Description | Units | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SI | Standard | ||

| characteristic length | m | ft | |

| fluid velocity | m/s | ft/s | |

| fluid density | kg/m^3 | slug/ft^3 | |

| fluid viscosity | Pa*s | lb*s/ft^2 | |

Examining the dimensions of the individual parameters, it becomes apparent that the Reynolds number is unit-less. The value represents the ratio of inertial forces to viscous forces in a fluid, and is useful in determining the relative importance of viscosity.[10] In inviscid flow, since the viscous forces are zero, the Reynolds number approaches infinity.[1] When viscous forces are negligible, the Reynolds number is much greater than one.[1] In such cases (Re>>1), assuming inviscid flow can be useful in simplifying many fluid dynamics problems.

Euler equations

In a 1757 publication, Leonhard Euler described a set of equations governing inviscid flow:[14]

| Symbol | Description | Units | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SI | Standard | ||

| material derivative | |||

| del operator | |||

| pressure | Pa | psi | |

| is the acceleration due to gravity | m/s^2 | ft/s^2 | |

Assuming inviscid flow, or negligible viscosity, allows the use of the Euler equation, and can apply to many examples of flow in which viscous forces are insignificant.[1] Some examples include flow around an airplane wing, upstream flow around bridge supports in a river, and ocean currents.[1]

In 1845, George Gabriel Stokes published another important set of equations, today known as the Navier-Stokes equations.[1][15] Claude-Louis Navier developed the equations first using molecular theory, which was further confirmed by Stokes using continuum theory.[1] The Navier Stokes equations describe the motion of fluids:[1]

When the flow is inviscid, or the viscosity can be assumed to be negligible, the Navier Stokes equation simplifies to the Euler equation:[1] This simplification is much easier to solve, and can apply to many types of flow in which viscosity is negligible.[1] Some examples include flow around an airplane wing, upstream flow around bridge supports in a river, and ocean currents.[1]

Solid boundaries

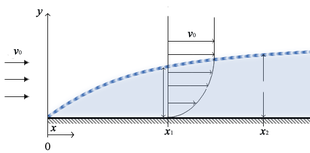

It is important to note, that negligible viscosity can no longer be assumed near solid boundaries, such as the case of the airplane wing.[1] In turbulent flow regimes (Re >> 1), viscosity can typically be neglected, however this is only valid at distances far from solid interfaces.[1] When considering flow in the vicinity of a solid surface, such as flow through a pipe or around a wing, it is convenient to categorize four distinct regions of flow near the surface:[1]

- Main turbulent stream: Furthest from the surface, viscosity can be neglected.

- Inertial sub-layer: The start of the main turbulent stream, viscosity has only minor importance.

- Buffer layer: The transformation between inertial and viscous layers.

- Viscous sub-layer: Closest to the surface, here viscosity is important.

Although these distinctions can be a useful tool in illustrating the significance of viscous forces near solid interfaces, it is important to note that these regions are fairly arbitrary.[1] Assuming inviscid flow can be a useful tool in solving many fluid dynamics problems, however, this assumption requires careful consideration of the fluid sub layers when solid boundaries are involved.

See also

- Viscosity

- Fluid dynamics

- Potential flow, a special case of inviscid flow

- Stokes flow, in which the viscous forces are much greater than inertial forces.

- Couette flow

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t E., Stewart, Warren; N., Lightfoot, Edwin (2007-01-01). Transport phenomena. Wiley. ISBN 9780470115398. OCLC 762715172.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b S.,, Stringari,. Bose-Einstein condensation and superfluidity. ISBN 9780198758884. OCLC 936040211.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Clancy, L.J., Aerodynamics, p.xviii

- ^ Kundu, P.K., Cohen, I.M., & Hu, H.H., Fluid Mechanics, Chapter 10, sub-chapter 1

- ^ "This Month in Physics History". www.aps.org. Retrieved 2017-03-07.

- ^ Landau, L. "Theory of the Superfluidity of Helium II". Physical Review. 60 (4): 356–358. doi:10.1103/physrev.60.356.

- ^ "nature physics portal - looking back - Going with the flow -- superfluidity observed". www.nature.com. Retrieved 2017-03-07.

- ^ HOUCK, J. R.; WARD, DENNIS (1979-01-01). "A LIQUID-HELIUM-COOLED GRATING SPECTROMETER FOR FAR INFRARED ASTRONOMICAL OBSERVATIONS". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 91 (539): 140–142.

- ^ "Cryogenics: Low temperatures, high performance | CERN". home.cern. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- ^ a b L., Bergman, Theodore; S., Lavine, Adrienne; P., Incropera, Frank; P., Dewitt, David (2011-01-01). Fundamentals of heat and mass transfer. Wiley. ISBN 9780470501979. OCLC 875769912.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Rott, N (2003-11-28). "Note on the History of the Reynolds Number". Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics. 22 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1146/annurev.fl.22.010190.000245.

- ^ Reynolds, Osborne (1883-01-01). "An Experimental Investigation of the Circumstances Which Determine Whether the Motion of Water Shall Be Direct or Sinuous, and of the Law of Resistance in Parallel Channels". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 174: 935–982. doi:10.1098/rstl.1883.0029. ISSN 0261-0523.

- ^ Stokes, G. G. (1851-01-01). "On the Effect of the Internal Friction of Fluids on the Motion of Pendulums". Transactions of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 9: 8.

- ^ Euler, Leonhard (1757). ""Principes généraux de l'état d'équilibre d'un fluide" [General principles of the state of equilibrium]". Mémoires de l'académie des sciences de Berlin. 11: 217–273.

- ^ Stokes, G. G. (1845). "On the Theories of the Internal Friction of Fluids in Motion and of the Equilibrium and Motion of Elastic Solids". Proc. Cambridge Phil. Soc. 8: 287–319.