Jean Froissart

Jean Froissart | |

|---|---|

Posthumous portrait of Jean Froissart, "Recueil d'Arras", Jacques Le Boucq | |

| Born | c. 1337 |

| Died | c. 1405 (aged 68-67) Chimay, County of Hainaut, Holy Roman Empire |

| Occupation(s) | author and court historian |

Jean Froissart (Old French, Middle French Jehan, c. 1337 – c. 1405) was a French-speaking medieval author and court historian from the Low Countries, who wrote several works, including Chronicles and Meliador, a long Arthurian romance, and a large body of poetry, both short lyrical forms, as well as longer narrative poems. For centuries, Froissart's Chronicles have been recognised as the chief expression of the chivalric revival of the 14th century Kingdom of England and Kingdom of France. His history is also an important source for the first half of the Hundred Years' War.

Life

What little is known of Froissart's life comes mainly from his historical writings and from archival sources which mention him in the service of aristocrats or receiving gifts from them. Although his poems have also been used in the past to reconstruct aspects of his biography, this approach is in fact flawed, as the 'I' persona which appears in many of the poems should not be construed as a reliable reference to the historical author. This is why de Looze has characterised these works as 'pseudo-autobiographical'.[1] Froissart came from Valenciennes in the County of Hainaut, situated in the western tip of the Holy Roman Empire, bordering France. Earlier scholars have suggested that his father was a painter of armorial bearings, but there is actually little evidence for this. Other suggestions include that he began working as a merchant but soon gave that up to become a cleric. For this conclusion there is also no real evidence, as the poems which have been cited to support these interpretations are not really autobiographical.

By about age 24, Froissart left Hainault and entered the service of Philippa of Hainault, queen consort of Edward III of England, in 1361 or 1362. This service, which would have lasted until the queen's death in 1369, has often been presented as including a position of court poet and/or official historiographer. Based on surviving archives of the English court, Croenen has concluded instead that this service did not entail an official position at court, and probably was more a literary construction, in which a courtly poet dedicated poems to his 'lady' and in return received occasional gifts as remuneration.[2]

Froissart took a serious approach to his work. He traveled in England, Scotland, Wales, France, Flanders and Spain gathering material and first-hand accounts for his Chronicles. He traveled with Lionel, Duke of Clarence, to Milan to attend and chronicle the duke's wedding to Violante, the daughter of Galeazzo Visconti. At this wedding, two other significant writers of the Middle Ages were present: Chaucer and Petrarch.

After the death of Queen Philippa, he enjoyed the patronage of Joanna, Duchess of Brabant among various others. He received rewards—including the benefice of Estinnes, a village near Binche and later became canon of Chimay—sufficient to finance further travels, which provided additional material for his work. He returned to England in 1395 but seemed disappointed by changes that he viewed as the end of chivalry. The date and circumstances of his death are unknown but St. Monegunda of Chimay might be the final resting place for his remains, although still unverified.

Legacy

Much more than his poetry, Froissart's fame is due to his Chronicles. The text of his Chronicles is preserved in more than 100 illuminated manuscripts, illustrated by a variety of miniaturists. One of the most lavishly illuminated copies was commissioned by Louis of Gruuthuse, a Flemish nobleman, in the 1470s. The four volumes of this copy (BNF, Fr 2643; BNF, Fr 2644; BNF, Fr 2645; BNF, Fr 2646) contain 112 miniatures painted by well-known Brugeois artists of the day, among them Loiset Lyédet, to whom the miniatures in the first two volumes are attributed. He is thought to have been one of the first to mention the use of the verge and foliot, or verge escapement in European clockworks, by 1368.

The English composer Edward Elgar wrote an overture entitled Froissart.

Works

- Froissart's Chronicles

- L'Horloge amoureux

- Méliador

Gallery

All miniatures by Loyset Liédet, unless stated otherwise.

-

Execution of Hugh the younger Despenser 1326. A miniature from the Gruuthuse copy of the Chronicle.

-

Battle of Sluys 1340 in the Gruuthuse MS.

-

Battle of Crécy, 1346 From a 15th-century illuminated manuscript of Jean Froissart's Chronicles (BNF, FR 2643, fol. 165v).

-

Battle of Neville's Cross, 1346. English victory over the Scots from the Gruuthuse manuscript.

-

John the Good, king of France, ordering the arrest of Charles the Bad, king of Navarre; from the Chroniques of Jean Froissart.

-

Battle of Poitiers 1356 (miniature of Froissart).

-

Defeat of the Jacquerie

9 June 1358 {BNF, FR 2643, fol. 226v, Jean Froissart, Chroniques, Flandre, Bruges XVe s} -

The Execution of Étienne Marcel and Jean Maillard 31 July 1358.

-

Richard II of England meets rebels, 1381 in the lively if pedestrian style of Loiset Lyédet from the Gruuthuse Froissart

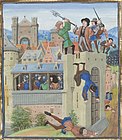

-

Death of Wat Tyler, leader of the Peasants Revolt 1381

-

Battle of Roosebeke (1382) Les chroniques de Froissart, mid-15th century

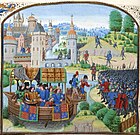

-

After the battle Roosebeke, Charles VI returns to Paris at the head of his army. The inhabitants of Paris negotiate with his envoys the terms of their surrender. Les Chroniques de Jean Froissart, mid-15th century

-

Battle of Otterburn (1388). Miniature from Jean Froissart, Chroniques . BNF, fr. 2645, fol. 351.

-

The Bal des Ardents (The Ball of the Burning Men), 1393. Jean Froissart miniature of 1450-80

-

Battle of Nicopoli, 1396, by the Master of the Dresden Prayer book from the Gruuthuse Froissart

-

Execution of prisoners after the Battle of Nicopoli Ms. Fr 2646, attr. to the Master of the Dresden Prayer Book

References

- ^ Laurence de Looze, Pseudo-Autobiography in the Fourteenth Century: Juan Ruiz, Guillaume de Machaut, Jean Froissart, and Geoffrey Chaucer (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1997).

- ^ Godfried Croenen, 'Froissart et ses mécènes: quelques problèmes biographiques', in Odile Bombarde (ed.), Froissart dans sa forge. Colloque réuni à Paris, du 4 au 6 novembre 2004, par M. Michel Zink, professeur au Collège de France, membre de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (Paris: Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 2006), 9-32.

Bibliography

- Peter Ainsworth, "Froissart, Jean", in Graeme Dunphy, Encyclopedia of the Medieval Chronicle, Leiden, Brill, 2010, pp. 642–645 (ISBN 90-04-18464-3).

- Cristian Bratu, "Je, aucteur de ce livre: Authorial Persona and Authority in French Medieval Histories and Chronicles." In Authorities in the Middle Ages. Influence, Legitimacy and Power in Medieval Society. Sini Kangas, Mia Korpiola, and Tuija Ainonen, eds. (Berlin/New York: De Gruyter, 2013): 183-204.

- Cristian Bratu, "Clerc, Chevalier, Aucteur: The Authorial Personae of French Medieval Historians from the 12th to the 15th centuries." In Authority and Gender in Medieval and Renaissance Chronicles. Juliana Dresvina and Nicholas Sparks, eds. (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012): 231-259.

- Cristian Bratu, "De la grande Histoire à l’histoire personnelle: l’émergence de l’écriture autobiographique chez les historiens français du Moyen Age (XIIIe-XVe siècles)." Mediävistik 25 (2012): 85-117.

External links

- Works by Jean Froissart at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Jean Froissart at the Internet Archive

- Bibliography Jean Froissart, compiled by Dr. Godfried Croenen, University of Liverpool.

- The Chronicles of Froissart, from Harvard Classics.

- The Online Froissart Project, by the University of Sheffield and the University of Liverpool.

- Jean Froissart, entry in the Encyclopedia Britannica.

- The Chronicles of Froissart Full 12 Volumes Edition online