Maunsell Forts

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2018) |

| Maunsell Sea Forts | |

|---|---|

| Thames and Mersey estuaries | |

"Navy" style fort | |

"Army" style fort | |

| Type | Fortified towers |

| Height | Approx 30–78 ft (9.1–23.8 m) |

| Site information | |

| Owner | |

| Open to the public | Yes, in some cases |

| Condition | Decommissioned in the late 1950s |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1942–1943 |

| In use | Second World War |

| Materials | Concrete, metals |

| Events | Used during Second World War |

The Maunsell Forts are towers built in the Thames and Mersey estuaries during the Second World War to help defend the United Kingdom. They were operated as army and navy forts, and named for their designer, Guy Maunsell.[1] The forts were decommissioned during the late 1950s and later used for other activities including pirate radio broadcasting. One of the forts is managed by the unrecognised Principality of Sealand;[2] boats visit the remaining forts occasionally, and a consortium named Project Redsands is planning to conserve the fort situated at Red Sands. The aesthetic attraction of the Maunsell forts has been considered to be associated with the aesthetics of decay, transience and nostalgia.[3]

During the summers of 2007 and 2008 Red Sands Radio, a station commemorating the pirate radio stations of the 1960s, operated from the Red Sands fort on 28-day Restricted Service Licences. The fort was subsequently declared unsafe, and Red Sands Radio has moved its operations ashore to Whitstable.

Forts had been built in river mouths and similar locations to defend against ships, such as the Grain Tower Battery at the mouth of the Medway dating from 1855, Plymouth Breakwater Fort, completed 1865, the four Spithead Forts: Horse Sand Fort, No Mans Land and St Helens Forts which were built 1865–1880 and Spitbank Fort, built during the 1880s, the Humber Forts on Bull & Haile Sands, completed in late 1919, and the Nab Tower, intended as part of a World War I anti-submarine defense but only set in place in 1920.

Maunsell naval forts

[edit]

The Maunsell naval forts were built in the Thames estuary and operated by the Royal Navy, to deter and report German air raids following the Thames as a landmark, and prevent attempts to lay mines by aircraft in this important shipping channel. There were four naval forts:

- Rough Sands (HM Fort Roughs) (U1) 51°53′43″N 1°28′50″E / 51.895194°N 1.480569°E

- Sunk Head (U2) 51°46′38″N 1°30′30″E / 51.7773°N 1.50841°E

- Tongue Sands (U3) 51°29′34″N 1°22′00″E / 51.492915°N 1.36662°E

- Knock John (U4) 51°33′44″N 1°09′43″E / 51.562277°N 1.162059°E

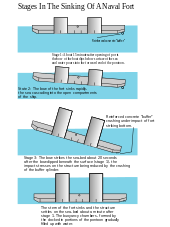

This artificial naval installation is similar in some respects to early "fixed" offshore oil platforms. It consisted of a rectangular 168-by-88-foot (51 by 27 m) reinforced concrete pontoon base with a support superstructure of two 60-foot (18 m) tall, 24-foot (7.3 m) diameter hollow reinforced concrete towers, walls roughly 3.5 inches (9 cm) thick; overall weight is estimated to have been approximately 4,500 tons.[4] The twin concrete supporting towers were divided into seven floors, four for crew quarters;[4] the remainder provided dining, operational, and storage areas for several generators, and for fresh water tanks and antiaircraft munitions. There was a steel framework at one end supporting a landing jetty and crane which was used to hoist supplies aboard; the wooden landing stage itself became known as a "dolphin".[4]

The towers were joined above the eventual waterline by a steel platform deck upon which other structures could be added; this became a gun deck, on which an upper deck and a central tower unit were constructed.[4] QF 3.7 inch anti-aircraft guns were positioned at each end of this main deck, with a further two Bofors 40 mm anti-aircraft guns and the central tower radar installations atop a central living area that contained a galley, medical, and officers quarters.

The design of these concrete structures is equal to a military grade bunker, due to the ends of the stilts (under water), that are locked into the ground. Many species of fish live near the forts because the forts create cover. They have provided landmark references for shipping. They were laid down in dry dock and assembled as complete units. They were then fitted out—the crews going aboard at the same time for familiarization—before being towed out and sunk onto their sand bank positions in 1942.

The naval fort design was the latest of several that Maunsell had devised in response to Admiralty inquiries. Early ideas had considered forts in the English Channel able to combat enemy vessels.

During World War II, the Thames estuary Navy forts destroyed one German E-Boat.[5]

Rough Sands Fort (U1)

[edit]Rough Sands fort was built to protect the ports of Felixstowe, Harwich and the town of Ipswich from aerial and sea attack. It is situated on Rough Sands, a sandbar located approximately 11 kilometres (6 nmi) from the coast of Suffolk and 13 kilometres (7 nmi) from the coast of Essex. Fort Roughs or the "Rough Towers" was "the first of originally four naval forts designed by G. Maunsell to protect the Thames Estuary". The artificial sea fort was constructed in dry dock at Red Lion Wharf, Gravesend,[4] and was commissioned "H.M. Fort Roughs" on 8 February 1942.[6] After an eventful journey its grounding was supervised by Maunsell at 16:45 on 11 February 1942.[7] With "almost 100 men" having earlier embarked at Tilbury docks, the fort began service immediately.[8]

In 1966 Paddy Roy Bates, who operated Radio Essex, and Ronan O'Rahilly, who operated Radio Caroline, landed on Fort Roughs and occupied it. However, after disagreements, Roy Bates seized the tower as his own. O'Rahilly attempted to storm the fort in 1967, but Roy Bates defended the fort with guns and petrol bombs and continued to occupy it. The British Royal Marines were alerted and the British authorities ordered Roy Bates to surrender. He and his son were arrested and charged, but the court dismissed the case as it did not have jurisdiction over international affairs: Roughs Tower lay beyond the territorial waters of Britain. Bates took this as de facto recognition of his country and seven years later issued a constitution, flag, and national anthem, among other things, for the Principality of Sealand (founded on 2 September 1967).[9]

Sunk Head Fort (U2)

[edit]Sunk Head fort was situated approximately 18 kilometres (10 nmi) from the coast off Essex and was grounded on 1 June 1942. The fort was decommissioned on 14 June 1945 though maintained until 1956 when it was abandoned. Unlike some of the other forts, Sunk Head was clearly well outside territorial waters, and when the Marine, &c., Broadcasting (Offences) Act 1967 came into effect in August 1967 the Government was anxious to ensure that it would not be taken over again by an offshore broadcaster. On 18 August 1967 Sunk Head was boarded by a contingent of the 24th Field Squadron of Royal Engineers from Maidstone from the tug Collie, commanded by Major David Ives. The Fort was weakened by acetylene cutting torches and 3,200 pounds of explosives were set. On 21 August 1967 Sunk Head was blown, leaving 20 feet of the leg stumps remaining.[10]

Tongue Sands Fort (U3)

[edit]Tongue Sands Fort was situated approximately 10.2 kilometres (6 nmi) from the coast off Margate, Kent and was grounded on 27 June 1942. On the night of 22/23 January 1945, fifteen German E-boats were seen on radar, with five close by. The S.119 or S.199 operating out of IJmuiden, Holland was just over 4 miles away and came under heavy fire from Tongue Sands Fort's 3.7-inch guns. The German E-Boat's captain was unsure of where the attack was coming from and manoeuvred to avoid being hit, ramming another E-Boat in the process. The captain scuttled his badly damaged vessel.[11]

The Tongue Sands Fort was decommissioned on 14 February 1945 and reduced to care and maintenance until 1949 when it was abandoned.[12] The fort had settled badly when it was grounded and as a result became unstable. On 5 December 1947 the Fort shook violently and sections began falling into the sea. The caretaker crew sent a distress call and were rescued by HMS Uplifter. Divers later established that the foundations were solid, but in a later storm the fort took on a 15 degree list.[12] During the mid-1960s under-scouring had further distorted the fort: large holes had appeared in east leg, sea water had flooded the lower levels and the platform had become detached with huge gaps between the deck. Tongue Sands Fort finally collapsed into the under-scouring hole during storms on 21/22 February 1996, leaving only a single 18 foot stump of the south leg remaining visible above sea level.[12]

Knock John Fort (U4)

[edit]

Knock John fort is situated approximately 16.1 kilometres (9 nmi) from the coast off Essex and was grounded on 1 August 1942. It was decommissioned on 14 June 1945 and evacuated on 25 June 1945. The platform was maintained until May 1956 when it was abandoned.[13] In 2009, it was observed that there was a slight distortion of the legs when viewing the tower from west to east. It is thought that underscouring is the cause of this.[14]

Maunsell army forts

[edit]

Maunsell also designed forts for anti-aircraft defence. These were larger installations comprising seven connected steel platforms. Four towers arranged in a semicircle ahead of the control centre and accommodation each carried a QF 3.7-inch gun, a tower to the rear of the control centre mounted Bofors 40 mm guns, while the seventh tower, set to one side of the gun towers and further out, was the searchlight tower.

Three forts were placed in Liverpool Bay:[15][16]

- Queens AA Towers

- Formby AA Towers

- Burbo AA Towers

and three in the Thames estuary:

- Nore (U5),

- Red Sands (U6)

- Shivering Sands (U7)

The Mersey forts were constructed at Bromborough Dock and the Thames forts at Gravesend.[17][18] Proposals to construct forts off the Humber, Portsmouth & Rosyth, Belfast & Londonderry came to nothing.[11] During World War II, the Thames estuary forts shot down 22 aircraft and about 30 flying bombs; they were decommissioned by the Ministry of Defence during the late 1950s.[citation needed]

Nore Fort (U5)

[edit]

Nore fort was the only one built in British territorial waters at the time it was established.[citation needed] Other forts were in international waters until the three-mile limit was extended to 12 nmi (14 mi; 22 km). The fort was damaged badly in 1953 during a storm,[19] then later in the year a Norwegian ship, Baalbek, collided with it, destroying two of the towers, killing four civilians and destroying guns, radar equipment and supplies. The ruins were considered a hazard to shipping and dismantled in 1959–1960. Parts of the bases were towed ashore by the Cliffe fort at Alpha wharf near the village of Cliffe, Kent, where they were still visible at low tide.[20]

Red Sands Fort (U6)

[edit]

There are seven towers in the Red Sands group at the mouth of the Thames Estuary. The towers had been connected by metal grate walk-ways. In 1959 consideration was given to refloating the Red Sands Fort and bringing the towers ashore but the costs were prohibitive.[21]

Radio 390 (1965–1967) was a pirate radio station on Red Sands Fort.

During the early 21st century, in response to proposals to demolish the fort, a group named Project Redsands was formed to try to preserve it. It was the only fort that could be visited safely from a platform in between the legs of one of the towers.[22] The fort was inspected by the structural engineering company Structural Repairs in 2021. They found that 6 of the towers had severe structural defects, with elements already lost to the sea, the 7th tower also had the same defects, with elements due to imminently fall into the sea. The fort could not be accessed safely in its present condition.[23]

Shivering Sands Fort (U7)

[edit]

This group was built near the Thames estuary for anti-aircraft defence and made up of several towers north of Herne Bay 9.2 mi (8.0 nmi; 14.8 km) from the nearest land. One of the seven towers collapsed in 1963 when fog caused the ship Ribersborg to stray off course and collide with one of the towers.[24] In 1964, the Port of London Authority placed wind and tide monitoring equipment on the Shivering Sands searchlight tower, which was isolated from the rest of the fort by the demolished tower. This relayed data to the mainland via a radio link. In August and September 2005, artist Stephen Turner spent six weeks living alone in the searchlight tower of the Shivering Sands Fort in what he described as "an artistic exploration of isolation, investigating how one's experience of time changes in isolation, and what creative contemplation means in a 21st-century context".[25]

Liverpool Army Forts

[edit]The Liverpool sea forts were constructed in the same way the forts in the Thames estuary were; they were designed to defend Liverpool and the industrial heartland of Liverpool from an aerial attack from the west. Originally 38 towers were intended to be built but only 21 towers were built (three forts). The forts were built from October 1941. No fort engaged in enemy action during WWII. Demolition of the structures started during the 1950s with these forts considered a priority over the Thames estuary ports due to being a hazard to shipping. Demolition was delayed in 1954 when the salvage ship working at Queens Fort was diverted to assist with the urgent demolition of The Nore Fort in the Thames Estuary, which had been damaged due to a collision with a Norwegian ship, leaving remains considered hazardous to shipping in the area. Demolition of the three forts was completed in 1955.[26]

Illicit radio stations

[edit]Various forts were re-occupied for pirate radio during the mid-1960s.

In 1964, a few months after Radios Caroline and Atlanta began broadcasting, Screaming Lord Sutch installed Radio Sutch in one of the towers at Shivering Sands. Sutch soon became bored with the project and sold the station to Reginald Calvert who had assisted in establishing the station and who renamed the station Radio City and expanded operations into all of the five towers that remained connected. Calvert's killing in a dispute concerning the station's ownership (found to be self-defence rather than murder) contributed to the Government passing legislation against the offshore stations in 1967.

During the illicit radio era the Port of London Authority frequently complained that its monitoring radio link was being disrupted by the nearby Radio City transmitter.

Red Sands was likewise occupied by Radio Invicta, which was renamed KING Radio and then Radio 390,[27] after its wavelength of approximately 390 metres. The station's managing director was ex-spy and thriller writer Ted Allbeury.[28]

The size of the Army forts made them ideal antenna platforms, since a large antenna could be based on the central tower and guyed from the surrounding towers.

A small group of radio enthusiasts established Radio Tower on Sunk Head Naval fort, but the station had a small budget, had poor coverage and lasted only a few months. Claims by the group that they also intended to provide television service from the fort were never credible. In order to prevent further illicit broadcasting, a team of Royal Engineers laid 2,200 lbs of explosive charges on Sunk Head, commencing on 18 August 1967. At 4:18 PM on 21 August the charges were detonated, destroying the entire superstructure and most of the concrete legs above the waterline.[29]

Paddy Roy Bates occupied the Knock John Fort in 1965 and established Radio Essex, later renamed BBMS—Britain's Better Music Station, but was better known for his post-pirate activities. After the termination of BBMS in late 1966 he moved the station's equipment to Roughs Tower, further from the coast, but did not recommence broadcasting. He, or a representative, has lived in Roughs Tower since 1967, self-styling the tower as the Principality of Sealand.[30]

Cultural references

[edit]The 1966 television series Danger Man episode "Not-so-Jolly Roger" was filmed partly at Redsands Army Sea Fort and includes an acknowledgement to Radio 390 in its closing credits. Redsands Fort was also used for the 1968 Doctor Who serial Fury from the Deep, in which the complex stood in for a North Sea gas refinery besieged by an intelligent seaweed creature.[31] In the 2020 film Artemis Fowl, the Redsands towers, seen from the air, appear as the exterior of a secret MI6 interrogation centre. In the 2013 movie The Hunger Games: Catching Fire, as the characters travel in a train along the coast, two Sea Forts can be seen in the water.

The Red Sands Fort and Radio City feature in the Glam Rock band, Slade's movie, Slade in Flame. The newly formed band, Flame, are interviewed by the pirate radio station, just as an attack is begun on the forts.

The Shivering Sands Forts, filmed from a North Sea ferry, appeared in the 1984 music video for the song "A Sort of Homecoming", by the Irish popular music band U2.[32]

The 2002 video game Reign of Fire features the forts during the dragon campaign, where remnants of British Armed Forces make a last stand during a dragon apocalypse.

The 2015 video game Stranded Deep includes abandoned Sea Forts that have the appearance of Maunsell Army Forts. These are difficult-to-find Easter Eggs built into the game for players to explore.

The setting of the 2023 science fiction film Last Sentinel is based on a structure modelled after a single tower of the Maunsell army forts.[33] [34]

The Red Sands Forts are seen in Episode 1 of Whitstable Pearl, mentioned as a drop-off and pick-up point for illicit drugs, as part of the story.

See also

[edit]- Admiralty M-N Scheme

- Sea fort

- Palmerston Forts – including several Sea Forts built on pre-existing islands or rocky islets, as well as some built directly upon the seabed

- Humber Forts

- Texas Towers

References

[edit]- ^ M.Rowland, Motor Mania – whitstable -. "KENT BOAT TRIPS FORTS THE MAUNSELL SEA FORTS JET SKI TOURS SEA TRIPS whitstable herne bay kent history books". www.whitstablescene.co.uk. Archived from the original on 23 January 2009. Retrieved 11 January 2005.

- ^ "PRINCIPALITY OF SEALAND". Sealand. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ at Chapter 3.5 in Moss, Joanne "Critical perspectives: North Sea offshore wind farms.: Oral histories, aesthetics and selected legal frameworks relating to the North Sea." (2021) https://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1611092/FULLTEXT01.pdf Retrieved 2 October 2023

- ^ a b c d e "The Rough Towers: Fort Specifications". The Harwich Society. Archived from the original on 18 August 2014. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ "Sea Forts History". www.offshoreradiomuseum.co.uk.

- ^ Turner, Frank R. (1994). The Maunsell Sea Forts. F.R. Turner. p. 74. ISBN 0-9524303-0-4.

- ^ Turner, Frank R. (1994). The Maunsell Sea Forts. F.R. Turner. p. 76. ISBN 0-9524303-0-4.

- ^ Turner, Frank R. (1994). The Maunsell Sea Forts. F.R. Turner. p. 83. ISBN 0-9524303-0-4.

- ^ "About | Principality of Sealand". Archived from the original on 20 February 2017. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- ^ "Sunk Head Tower". www.offshoreradiomuseum.co.uk.

- ^ a b "Fort Fanatics". www.bobleroi.co.uk.

- ^ a b c "Tongue Sands Fort". www.offshoreradiomuseum.co.uk.

- ^ "Knock John Fort". www.offshoreradiomuseum.co.uk.

- ^ "Fort Fanatics". www.bobleroi.co.uk.

- ^ Turner, Frank R. (1995). The Maunsell Sea Forts. F.R. Turner. p. 84. ISBN 0-9524303-1-2.

- ^ "Thread on WorldNavalShips.com giving more details of the forts".

- ^ Turner, Frank R. (1995). The Maunsell Sea Forts. F.R. Turner. p. 18. ISBN 0-9524303-1-2.

- ^ Turner, Frank R. (1995). The Maunsell Sea Forts. F.R. Turner. p. 90. ISBN 0-9524303-1-2.

- ^ Ashton, Ben (6 January 2020). "Full story behind the bizarre abandoned structures just off the east Kent coast". KentLive.

- ^ "Thames Maunsell Forts::Nore Fort (remains)". subterrain.org.uk.

- ^ "Red Sands Fort". www.offshoreradiomuseum.co.uk.

- ^ "Thames Maunsell Forts::Red Sands Fort". subterrain.org.uk.

- ^ "Plans to restore Maunsell Forts off Kent coast". Kent Online. 27 July 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ "Thames Maunsell Forts::Shivering Sands Fort". subterrain.org.uk.

- ^ www.macmedicine.net. "Stephen Turner – Seafort Project". www.seafort.org.

- ^ "Mersey Forts". www.offshoreradiomuseum.co.uk.

- ^ "Radio 390". www.offshoreradiomuseum.co.uk. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ Johnson, Michael (3 January 2006). "Obituary: Ted Allbeury". the Guardian. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ Bishop, Gerry (1975). Offshore Radio. Iceni Enterprises, Norwich. ISBN 0-904603-00-8.

- ^ "The Principality of Sealand – Become Part Of Sealand's Royal Peerage". Principality of Sealand.

- ^ "Fury from the Deep ★★★★". Radio Times.

- ^ U2Archive (11 January 2012). "U2 – A Sort Of Homecoming Live [HD]" – via YouTube.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Last Sentinel (2023) – IMDb". IMDb.

- ^ "Tanel Toom's Last Sentinel".

Further reading

[edit]- Turner, Frank R. (1995). The Maunsell Sea Forts. F.R. Turner. ISBN 0-9524303-0-4. (3 volumes, ISBN 0-9524303-0-4; ISBN 0-9524303-1-2; ISBN 0-9524303-7-1)

- Kauffmann, J.E. and Jurga, Robert M. Fortress Europe: European Fortifications of World War II, Da Capo Press, 2002. ISBN 0-306-81174-X

External links

[edit]- Maunsell Sea Forts information

- Guide to Sea Forts Archived 18 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine from HerneBayOnline

- Project Redsand from project-redsand.com

- Red Sands Radio official website

- Maunsell Towers from undergroundkent.co.uk

- Map of the Forts from BenvenutiaSealand.it (English version via Google Translate)

- 20th-century forts in England

- Artificial islands of England

- British World War II defensive lines

- History of the Royal Navy

- History of the North Sea

- Geography of the River Thames

- North Sea offshore buildings and structures

- Pirate radio

- River Mersey

- Sea forts

- Thames Estuary

- Towers

- World War II sites in England

- 1942 establishments in England