Lorentz factor

The Lorentz factor or Lorentz term is the factor by which time, length, and relativistic mass change for an object while that object is moving. The expression appears in several equations in special relativity, and it arises in derivations of the Lorentz transformations. The name originates from its earlier appearance in Lorentzian electrodynamics – named after the Dutch physicist Hendrik Lorentz.[1]

Due to its ubiquity, it is generally denoted with the symbol γ (Greek lowercase gamma). Sometimes (especially in discussion of superluminal motion) the factor is written as Γ (Greek uppercase-gamma) rather than γ.

Definition

The Lorentz factor is defined as:[2]

where:

- v is the relative velocity between inertial reference frames,

- β is the ratio of v to the speed of light c.

- τ is the proper time for an observer (measuring time intervals in the observer's own frame),

- t is coordinate time

- c is the speed of light in a vacuum.

This is the most frequently used form in practice, though not the only one (see below for alternative forms).

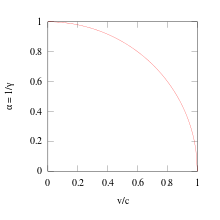

To complement the definition, some authors define the reciprocal:[3]

see velocity addition formula.

Occurrence

Following is a list of formulae from Special relativity which use γ as a shorthand:[2][4]

- The Lorentz transformation: The simplest case is a boost in the x-direction (more general forms including arbitrary directions and rotations not listed here), which describes how spacetime coordinates change from one inertial frame using coordinates (x, y, z, t) to another (x' , y' , z' , t' ) with relative velocity v:

Corollaries of the above transformations are the results:

- Time dilation: The time (∆t' ) between two ticks as measured in the frame in which the clock is moving, is longer than the time (∆t) between these ticks as measured in the rest frame of the clock:

- Length contraction: The length (∆x' ) of an object as measured in the frame in which it is moving, is shorter than its length (∆x) in its own rest frame:

Applying conservation of momentum and energy leads to these results:

- Relativistic mass: The mass of an object m in motion is dependent on and the rest mass m0:

- Relativistic momentum: The relativistic momentum relation takes the same form as for classical momentum, but using the above relativistic mass:

- Relativistic kinetic energy: The relativistic kinetic energy relation takes the slightly modified form:

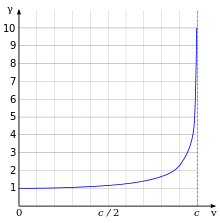

Numerical values

In the table below, the left-hand column shows speeds as different fractions of the speed of light (i.e. in units of c). The middle column shows the corresponding Lorentz factor, the final is the reciprocal. Values in bold are exact.

| Speed (units of c) | Lorentz factor | Reciprocal |

|---|---|---|

| 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| 0.050 | 1.001 | 0.999 |

| 0.100 | 1.005 | 0.995 |

| 0.150 | 1.011 | 0.989 |

| 0.200 | 1.021 | 0.980 |

| 0.250 | 1.033 | 0.968 |

| 0.300 | 1.048 | 0.954 |

| 0.400 | 1.091 | 0.917 |

| 0.500 | 1.155 | 0.866 |

| 0.600 | 1.250 | 0.800 |

| 0.700 | 1.400 | 0.714 |

| 0.750 | 1.512 | 0.661 |

| 0.800 | 1.667 | 0.600 |

| 0.866 | 2.000 | 0.500 |

| 0.900 | 2.294 | 0.436 |

| 0.990 | 7.089 | 0.141 |

| 0.999 | 22.366 | 0.045 |

| 0.99995 | 100.00 | 0.010 |

Alternative representations

There are other ways to write the factor. Above, velocity v was used, but related variables such as momentum and rapidity may also be convenient.

Momentum

Solving the previous relativistic momentum equation for γ leads to:

This form is rarely used, it does however appear in the Maxwell–Jüttner distribution.[5]

Rapidity

Applying the definition of rapidity as the following hyperbolic angle φ:[6]

also leads to γ (by use of hyperbolic identities):

Using the property of Lorentz transformation, it can be shown that rapidity is additive, a useful property that velocity does not have. Thus the rapidity parameter forms a one-parameter group, a foundation for physical models.

Series expansion (velocity)

The Lorentz factor has the Maclaurin series:

which is a special case of a binomial series.

The approximation γ ≈ 1 + 1/2 β2 may be used to calculate relativistic effects at low speeds. It holds to within 1% error for v < 0.4 c (v < 120,000 km/s), and to within 0.1% error for v < 0.22 c (v < 66,000 km/s).

The truncated versions of this series also allow physicists to prove that special relativity reduces to Newtonian mechanics at low speeds. For example, in special relativity, the following two equations hold:

For γ ≈ 1 and γ ≈ 1 + 1/2 β2, respectively, these reduce to their Newtonian equivalents:

The Lorentz factor equation can also be inverted to yield:

This has an asymptotic form of:

The first two terms are occasionally used to quickly calculate velocities from large γ values. The approximation β ≈ 1 - 1/2 γ−2 holds to within 1% tolerance for γ > 2, and to within 0.1% tolerance for γ > 3.5.

Applications in astronomy

The standard model of long-duration gamma-ray bursts (GRBs) holds that these explosions are ultra-relativistic (initial greater than approximately 100), which is invoked to explain the so-called "compactness" problem: absent this ultra-relativistic expansion, the ejecta would be optically thick to pair production at typical peak spectral energies of a few 100 keV, whereas the prompt emission is observed to be non-thermal.[7]

See also

References

- ^ One universe, by Neil deGrasse Tyson, Charles Tsun-Chu Liu, and Robert Irion.

- ^ a b Forshaw, Jeffrey; Smith, Gavin (2014). Dynamics and Relativity. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-93329-9.

- ^ Yaakov Friedman, Physical Applications of Homogeneous Balls, Progress in Mathematical Physics 40 Birkhäuser, Boston, 2004, pages 1-21.

- ^ Young; Freedman (2008). Sears' and Zemansky's University Physics (12th ed.). Pearson Ed. & Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-321-50130-1.

- ^ Synge, J.L (1957). The Relativistic Gas. Series in physics. North-Holland. LCCN 57-003567

- ^ Kinematics, by J.D. Jackson, See page 7 for definition of rapidity.

- ^ Cenko, S. B. et al., iPTF14yb: The First Discovery of a Gamma-Ray Burst Afterglow Independent of a High-Energy Trigger, Astrophysical Journal Letters 803, 2015, L24 (6 pp).

External links

- Merrifield, Michael. "γ – Lorentz Factor (and time dilation)". Sixty Symbols. Brady Haran for the University of Nottingham.

- Merrifield, Michael. "γ2 – Gamma Reloaded". Sixty Symbols. Brady Haran for the University of Nottingham.