Lydenburg heads

| Lydenburg Heads | |

|---|---|

The Lydenburg heads are the earliest known examples of African sculpture in Southern Africa. | |

| |

| Material | terracotta |

| Created | African Iron Age A.D. 500 |

| Discovered | Lydenburg, Mpumalanga, South Africa |

| Present location | Iziko South African Museum, Cape Town |

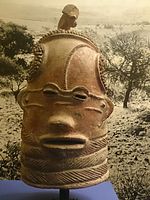

The Lydenburg Heads are seven terracotta heads that were discovered in association with other pottery artifacts in Lydenburg, Mpumalanga, South Africa. They are among the oldest known African Iron Age artworks from South of the equator.[1] Other artefacts found in association with these heads include ceramic vessels, iron and copper beads, and bone fragments. Charcoal associated with the heads was radiocarbon dated, and this relative dating technique places these artifacts and the site at around 1410 BP (approximately 500 A.D.), which constitutes one of the earliest dates for an Iron Age settlement in South Africa.[2] The heads are hollow with thin clay strips added to create facial details. The skill and thought that went into the designs suggest that they were valued products of a well organised and settled community.[3]

Discovery

[edit]The heads were discovered initially as a surface find[4] by a young boy named Karl-Ludwig von Bezing while playing on his father's farm. The material was later collected when Ludwig was a teenager.[5] He went back in both 1962 and 1966 to excavate the area and during this time he was able to find several pieces of pottery that proved to be seven hollow heads when assembled,[2] two of which can fit over a child's head; only one out of the seven heads resembles an animal.[1]

Artifacts

[edit]

The recovered pottery shards were reconstructed largely at the University of Cape Town, and assembled into two large heads and five smaller heads. One of the larger heads constitute an incomplete specimen.[6] The reconstructed heads provide a glimpse into the craftsmen's skill and preciseness of artistry, even though they may not look exactly how they looked 1500 years ago. Six of the heads share human characteristics, while a single head has animal-like features. The presence of linear patterned neck rings are postulated to represent a marker of prosperity or wealth, due to their symbolic use throughout time.[7] Of the seven, only two are large enough to have been worn, but the size is not the only observable variation between them. The two aforementioned heads constitute the only specimens with small animal figurines, perceived to be lions, mounted on top of them.[7] The other five are more similar in size and appearance, with one exception. This head is the only head that seems to resemble something other than a human. It has a long snout instead of regular protruding lips and also has no ears.[8] Documentation of associated artefacts was limited due to the primary significance of the heads; however, we do know that the associated pottery sherds were identified as terracotta.

These heads are speculated to have been covered in white slip, and glittering specularite at the time of their use. The smaller heads, #3–7 have small perforations on their sides. These perforations may have been some sort of framework to be worn as a headdress, or some part of a significant structure.[5]

Characteristics

[edit]The heads share a basic pot like formation with subtle differences in the way they were each shaped. The base formed at the bottom of all the heads was completed like the rim of a pot. Parts of the rim are rounded, however some parts of the base reflects a flat squared shape. While the Basal rings may be incised or moulded the neck rings above these basal rings contain diagonally incised rings that circle the entire neck. The incised pattern constitutes hatch marks that alternate in direction producing a herringbone pattern. While the specimens are similar in manufacture, they also have varying characteristics.[6] Some specimens are better preserved than others, as in the case of the ears. The ears were all manufactured in the same way. A plate of clay was moulded to the side of the specimen where the ear would be anatomically. The outer edge of the ears were rounded and sloped down and slightly forward. Ear lobes are not presented in any of the specimens however there is a small peg of clay placed above the area where the ear attached to the head. This clay peg is postulated to represent the cartilaginous projection usually found in a normal human ear. Each head features similar notched ridges made by applying wet strips of clay and incising lines before the clay had dried. These notches vary in position and shape along the face.[5] Other similar features include the eyes, mouth and nose; these characteristics are detailed below.

Head #1

[edit]The basal neck rings are moulded on this head. The mouth is located directly above the upper neck ring. Two crescent shaped pieces of clay were joined at the edges to form the lips which then taper into the cheeks. The lips are open approximately 10mm. The lips have been cut completely through to the face which constitutes an open mouth that includes no teeth. The eyes are placed in the middle of the face. The eyes are made by slits cut through to the wall of the faced. The left and right ears are intact. There are three horizontal notched ridges on the face located one above the other. One notched ridge is found between the eyes running vertical. Two sets of horizontal notches are located towards the side of the face placed between the outer eye socket and the placement of the ears. The horizontal ridges found below the placement of the eyes are not notched, they constitute smooth raised ridges. This is the only head with smooth ridges. Above the crown outlining the edge of the face are groupings of clay studs. These features are only seen in this head specifically and portions of Head No. 2[5]

Head #2

[edit]This head is too fragmented for precise characteristic recording. The basal neck rings are moulded. The mouth is located directly above the upper neck ring. Two crescent shaped pieces of clay were joined at the edges to form the lips which then taper into the cheeks. The lips have been cut completely through to the face which constitutes an open mouth that includes no teeth. The eyes are placed in the middle of the face. The eyes are made by slits cut through to the wall of the faced. The left ear is intact. The ridges on this head are similar to those in Head No. 1 except the horizontal ridges below the eyes are incised with notches and not smooth. There are two vertical ridges with incised notches located between the eyes and extend toward the upper most portion of the forehead. There is a grouping of several applied clay studs on one of the pieces that constitute this head as seen in Head No. 1[5]

Head #3

[edit]Head # 3 has perforations that measure approximately 5 mm in diameter on both sides of the neck toward the lower portion of the hatched rings. The basal neck rings are incised. The mouth is within the upper neck ring. Two crescent shaped pieces of clay were joined at the edges to form the lips which then taper into the cheeks. The lips are open approximately 5 mm. Teeth were made by inserting clay pegs between the lip gaps. There is a large gap depicted between the two front teeth. The eyes are placed in the middle of the face. The eyes were made by cutting into applied pieces of clay. The left ear is intact. This head has three horizontal ridges with incised lines between the eyes. A single ridge extending towards the forehead is also notched and curves toward the left side of the face. There are single notched ridges extending from the eye to the top part of the ear on both sides of the head. Below these, a notched ridge extends horizontally across the cheek to the bottom of the ear.[5]

Head #4

[edit]This head has perforations that measure approximately 5 mm in diameter on both sides of the neck toward the lower portion of the hatched rings. The basal neck rings are insiced. The mouth is within the upper neck ring. Two crescent shaped pieces of clay were joined at the edges to form the lips which then taper into the cheeks. The lips are open approximately 5 mm. Teeth were made by inserting clay pegs between the lip gaps. There is a large gap depicted between the two front teeth. The eyes are placed in the middle of the face. The eyes were made by cutting into applied pieces of clay. The left and right ears are intact. The notched ridges in this specimen are similar to Head # 3 except the ridge on the right side of the face extending across the cheek is not intact.[5]

Head #5

[edit]This head has perforations that measure approximately 5 mm in diameter on both sides of the neck toward the lower portion of the hatched rings. The basal neck rings are incised. This head has the only example of cross hatching on the neck. The mouth is within the upper neck ring. Two crescent shaped pieces of clay were joined at the edges to form the lips which then taper into the cheeks. The lips are open approximately 5 mm. Teeth were made by inserting clay pegs between the lip gaps. There is a large gap depicted between the two front teeth. The eyes are placed in the middle of the face. The eyes were made by cutting into applied pieces of clay. There are three horizontal notched ridges between the eyes. The orientation of notched ridges are similar to Heads No. 2, #3, and No. 4. All Ridges on face are notched. The vertical notched ridge extends in a straight line from the middle eye ridges across the forehead; unlike the previous mentioned heads whose forehead ridges curve to one side of the head.[5]

Head #6

[edit]This head has perforations that measure approximately 5 mm in diameter on both sides of the neck toward the lower portion of the hatched rings. The basal neck rings are incised. The mouth is missing in this specimen. The eyes are placed towards the lower portion of the face. The eyes were made by cutting into applied pieces of clay. The right eye is missing. The left ear is intact. The ridge patterning on the face is similar to Heads No. 2, #3, and No. 4. This includes three incised ridges running horizontal between the eyes, one ridge running horizontal from the outer corner of the eye to the top of the ear, on both sides; and one notched ridge extending across the cheek to the bottom of the ear on both sides of the face. The major difference in this specimen is that the single, vertical, notched-ridge extending from the middle of the eye ridges across the forehead, curves to the right of the face.[5]

Head #7

[edit]This head has perforations that measure approximately 5 mm in diameter on both sides of the neck toward the lower portion of the hatched rings. The basal neck rings are incised. The mouth appears as a protruding snout, that has a downward slope which flares out over the upper most neck ring. Teeth were made by inserting clay pegs between the lip gaps. There is a large gap depicted between the two left side teeth. This specimen represents a differing morphology compared to the other six heads. The face of this specimen was created to bulge outwards and down wards with the nose being set low towards the exaggerated lips. The positioning of the lips and nose give this head the appearance of an animal snout. The eyes were made by cutting into applied pieces of clay. This head does not have ears like the other specimens. The notched ridges on this head Varies widely from the previous specimens. Where the other heads share three notched ridges between the eyes, this specimen has a long notched ridge extending from the protruding mouth vertically between the eyes towards the forehead which then curves to the left side of the face. Like the other heads Head No. 7 had horizontal notched ridges extending from the outer corner of the eyes, but these ridges slope downward to the bottom of where ears would be positioned. There are no horizontal ridges running across the cheek as in the other specimens.[5]

Speculative purpose

[edit]

The current speculation surrounding the Lydenburg Heads is that they may have been created to serve ritualistic and or ceremonial purposes including initiation rights.[8] The two larger specimens could have been worn by a small individual such as young man. If so, these heads may represent a significant point in a boy's life such as becoming a man, or ceremonial purposes like memorialising an ancestor.[7] The five smaller heads have holes in their sides which some archaeologists suggest may have been used to connected them to something at the time of their use.[8] The marks across the foreheads and between the eyes are postulated to represent scarification marks, a widely practice behaviour in Africa. However, no evidence of scarification is seen practised within the modern descendants of those who manufactured the heads.[5] Researchers suggest that the heads may not have been just disposed of but purposely buried,[9] or destroyed at the conclusion of a specified ceremony,[4] which may indicate their significance. These heads may be a result of ceremonial ritual or aggrandizement of significant ancestors. The heads show characteristics of several different groups throughout the continent including; The Bantu, The Ndebele, and The Bini.[5]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Lydenburg Heads (ca. 500) | Thematic Essay | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ a b Whitelaw, Gavin (1996). "Lydenburg Revisited: Another Look at The Mpumalanga Early Iron Age Sequence". The South African Archaeological Bulletin.

- ^ Nelson, Jo (2015). Historium. China: Big Picture Press. p. 10.

- ^ a b Evers, T.M. (1982). "Excavations at the Lydenburg Heads Site, Eastern Transvaal, South Africa". South African Archaeological Bulletin. 37: 16–33.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Inskeep, R. R.; Maggs, T. M. O'C. (1 January 1975). "Unique Art Objects in the Iron Age of the Transvaal, South Africa". The South African Archaeological Bulletin. 30 (119/120): 114–138. doi:10.2307/3888099. JSTOR 3888099.

- ^ a b Inskeep, R.R. (May 1975). "Unique Art Objects in the Iron Age of the Transvaal, South Africa". South African Archaeological Bulletin.

- ^ a b c Maggs, Tim; Davison, Patricia (1 February 1981). "The Lydenburg Heads". African Arts. 14 (2): 28–88. doi:10.2307/3335725. JSTOR 3335725.

- ^ a b c "Lydenburg Heads (ca. 500)". Timeline of Art History. Metropolitan Museum of Art. October 2003. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ "Mysterious Creators of Lydenburg Heads - MessageToEagle.com". www.messagetoeagle.com. Retrieved 9 December 2015.