Marie Meyer (aviator)

Marie Meyer | |

|---|---|

Marie on a Flint Motor car, 1924 | |

| Born | Marie Meyer January 17, 1899 Illinois, U.S.[vague] |

| Died | May 24, 1956 (aged 57) Hot Springs, Arkansas, U.S. |

| Burial place | Macon, Missouri, U.S. |

| Spouse |

Charles Lee Fower (m. 1924) |

Marie Meyer (January 17, 1899 – May 24, 1956), later Marie Meyer Fower, was an American barnstorming pilot who ran the Marie Meyer Flying Circus in the United States in the 1920s.[1][2] She was a pilot, a wingwalker and a parachutist.[2] She competed in international air races in both St. Louis and Dayton.[3]

Early life

[edit]Marie Meyer was born in Illinois on January 17, 1899. Soon after her parents, John and Dora Meyer, moved to St. Louis, Missouri. After graduating from high school, Marie worked in a store and saved money for flying lessons. She learned to fly with William B. Robertson, who opened a flying school in 1918 at the St. Louis Flying Field. St. Louis was one of a few cities in the United States to have a civilian airfield. Meyer completed her last hour of practice flying in 1921, at the State Fair in Sedalia.[2][4]

Career

[edit]

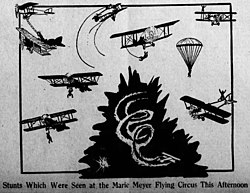

By 1922, Marie had earned her pilot’s license, bought one of the training "Jennies" being sold off by the US Army, and formed the Marie Meyer Flying Circus.[2][5] The Marie Meyer Flying Circus performed at state fairs across the American Midwest. Her pilots included Charles Lee Fower, Joe Hammer, Jimmie Donohue, John Hunter,[2][3] Joe Lawrence, Frank Dunn,[6] and even Charles Lindbergh during his barnstorming days.[2][3] At one point, future NASA scientist Robert T. Jones worked for the Marie Meyer Flying Circus. He took flying lessons in return for doing engineering maintenance jobs, "carrying gas and patching wing tips".[7][8] Marie was successful in getting sponsorships from companies such as Flint automobiles and Texaco oil and gas, who partnered with her in advertising.[9][10] Companies such as the Jefferson County Oil Company donated oil and gas for events.[11]

Marie Meyer performed as a pilot, a wingwalker and a parachutist.[2][5] The stunts she performed included standing on the upper wing of the biplane while it looped-the-loop, sometimes while holding a rope and sometimes with her feet tucked into stirrups so she could wave to the audience.[3] Another stunt was to leap from the lower wing of the plane while wearing a parachute.[3][12][13] Meyer also hired Elbert “Bertie” Brooks, a trapeze artist, to perform while hanging below the plane.[2]

-

Marie on the lower wing, 1924

-

Marie on the top wing, 1924

-

Marie looping the loop, 1925

-

Cartoon of trapeze artist “Bertie” Brooks, 1924

In 1924, the Marie Meyer Flying Circus did a benefit performance on behalf of the St. Louis airfield. To promote the event, the St. Louis Flying Club asked Marie to stand on top of her plane while flying along a downtown St. Louis street, between buildings. The St. Louis Safety Council protested that such a stunt would be too dangerous, but the planners went ahead. The stunt was planned for lunch hour on June 24, 1924, but the flying conditions that day were terrible. At 1:30 p.m. Charles Fower finally flew the plane down the street. Marie Meyer was able to stand upright briefly, holding a rope, but had to drop back onto the wing due to wind gusts. The plane came dangerously close to the top of the Railway Exchange Building.[2]: 34–35 [14] Years later, Meyer told a reporter:[2]: 34–35

"We never had an accident, or lost a life with the circus, but no one will ever know how close we came to ending it all that day... We did give them a show though!"[2]: 34–35

In 1924[2] Marie Meyer married stunt pilot Charles Lee Fower. Fower was born in Macon, Missouri on December 23, 1894.[1] The Marie Meyer Flying Circus continued to operate until 1928 or 1929. Flying was becoming less novel for the spectators, stunts were more regulated, and owning and running aircraft was becoming more expensive.[2] By 1929, the circus was down to its last Standard J-1.[8]

Marie and her husband moved to Macon, where they ran several businesses reflecting the trends of the times. The Fower Oil Company met the need for gas for increasingly popular cars, while Louie's Sweet Shop took advantage of the availability of electricity to serve sodas and ice cream. They kept one of their planes and bought a farm outside of town, where they built a private landing strip. In 1965, Charles Fower donated the landing strip to the city. It became the Macon Fower Memorial Airport.[1][2]

Marie Meyer and Charles Fower were honored in 1953 by the St. Louis Chapter of the National Aviation Academy (NAA) for "contributing materially to the progress of aviation by exhibiting faith in the future of powered flight during the dawn of the air age".[1][15]

Marie died in a car accident in Hot Springs, Arkansas on May 24, 1956, while traveling with friends.[16][17][3] Charles died on February 2, 1967. They are buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in Macon.[2]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Famous Maconites: Charles Lee Fower and Marie Meyer Fower". Macon, Missouri's Sesquicentennial Celebration!. Archived from the original on January 27, 2022. Retrieved February 23, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Montgomery, Christine (2015). Marie Meyer Fower : barnstormer (PDF). Kirksville, Missouri: Truman State University Press. ISBN 978-1-61248-149-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 23, 2020. Retrieved February 23, 2023.[unreliable source?]

- ^ a b c d e f Cooper, Joan (1999). "Marie Meyer's Flying Circus". In Corbett, Katharine T. (ed.). In her place : a guide to St. Louis women's history. St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society Press. pp. 241–242. ISBN 978-1883982300. Archived from the original on February 24, 2023. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- ^ Thomasson, Ellen Messerly (Summer 2003). "Nerve and Cold Courage: Early women fliers in St. Louis". Gateway Heritage: The Magazine of the Missouri Historical Society. 24 (1): 28–33.

- ^ a b "Marie Meyer Fower, a Missouri Barnstormer". John Hare. Archived from the original on February 23, 2023. Retrieved February 23, 2023.

- ^ "Flying circus pleases crowd today". The Intelligencer (via Wikipedia Library). Vol. 45, no. 165. Mexico, MO. August 1, 1924. p. 1.

- ^ Vincenti, Walter G. (January 1, 2005). "Robert T. Jones, One of a Kind". Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics. 37 (1): 1–21. Bibcode:2005AnRFM..37....1V. doi:10.1146/annurev.fluid.36.050802.122008. ISSN 0066-4189. Archived from the original on December 15, 2019. Retrieved February 22, 2023.

- ^ a b Jones, R. T. (January 1977). "Recollections From an Earlier Period in American Aeronautics". Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics. 9 (1): 1–12. Bibcode:1977AnRFM...9....1J. doi:10.1146/annurev.fl.09.010177.000245. ISSN 0066-4189. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- ^ "Three-wheeled Flint Car Carries Woman Stunt Flyer". St Louis Globe Democrat. July 6, 1924. p. 1.

- ^ "Advertisement for Texaco gasoline and motor oils, as used by the Marie Meyer Flying Circus". The Muscatine Journal. October 2, 1925. p. 12.

- ^ "Flying circus held last week a big success". Jefferson County Republican. Vol. XXXIII, no. 41. October 2, 1924. p. 1.

- ^ "Daredevils". Digital Public Library of America. Archived from the original on February 24, 2023. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- ^ Cox, Jeremy R. C. (2011). St. Louis Aviation. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-0-7385-8410-2. Archived from the original on February 24, 2023. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- ^ "Downtown crowds given thrill by stunt flyers". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Vol. 76, no. 290. June 24, 1924. p. 1.

- ^ "Fowers honored for pioneering in aviation". Macon Chronicle-Herald. Macon, Missouri. December 18, 1953. p. 1.

- ^ "Two Macon women, one a flying circus performer, die in car". Sedalia Democrat Newspaper Archives (available via Wikipedia Library). May 25, 1956. p. 11.

- ^ Moon, Katie J. (October 23, 2020). Groundbreakers, rule-breakers & rebels : 50 unstoppable St. Louis women. St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-1883982980. Archived from the original on February 23, 2023. Retrieved February 23, 2023.

External links

[edit] Media related to Marie Meyer at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Marie Meyer at Wikimedia Commons