The 13 Martyrs of Arad

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2014) |

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Hungarian. (September 2021) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

The Thirteen Martyrs of Arad (Hungarian: aradi vértanúk) were the thirteen Hungarian rebel generals who were executed by the Austrian Empire on 6 October 1849 in the city of Arad, then part of the Kingdom of Hungary (now in Romania), after the Hungarian Revolution (1848–1849). The execution was ordered by the Austrian general Julius Jacob von Haynau.

Background

[edit]In a historic speech on 3 March 1848, shortly after news of the revolution in Paris had arrived, Lajos Kossuth demanded parliamentary government for Hungary and constitutional government for the rest of Austria. The Revolution started on 15 March 1848, and after military setbacks in the winter and a successful campaign in the spring, Kossuth declared independence on 19 April 1849. By May 1849, the Hungarians controlled all of the country except Buda, which they won after a three-week bloody siege. The hopes of ultimate success, however, were frustrated by the intervention of Russia.

After all appeals to other European states failed, Kossuth abdicated on 11 August 1849, in favor of Artúr Görgei, who he thought was the only general capable of saving the nation. On 13 August 1849, Görgei signed a surrender at Világos (now Șiria, Romania) to the Russians, who handed the army over to the Austrians.[1] At the insistence of the Russians, Görgei was spared. The Austrians took reprisals on other officers of the Hungarian army.

The thirteen Hungarian generals were executed by hanging at Arad on October 6, 1849, with the exception of Arisztid Dessewffy and two others, because of their friendship to the Prince of Luxembourg. A hanging was deemed a humiliation, so they were executed by a firing squad of 12. On the same day, Count Lajos Batthyány (1806–1849), the first Hungarian prime minister, was executed in Pest at an Austrian military garrison.

Kossuth fled to the Ottoman Empire; he maintained that Görgei alone was responsible for the failure of the rebellion, calling him "Hungary's Judas".[2] Others, looking at the impossible situation Görgei was given, have been more sympathetic. They have said that, given the circumstances, he was left with no option other than surrender.

One of the public squares contains a martyrs' monument, erected in the memory of the generals. It consists of a colossal figure of Hungary, with four allegorical groups, and medallions of the executed generals.

Hungarians have come to regard the thirteen rebel generals as martyrs for defending the cause of freedom and independence for their people. The majority of the generals were not of ethnic Hungarian origin,[3] but they fought for the cause of an independent and — for its age — liberal Hungary. Baron Gyula Ottrubay Hruby, who was also executed in Arad, was actually Czech and spoke German, while Damjanich was of Serb origin. The anniversary of their execution is remembered on October 6 as a day of mourning for Hungary.[4]

The generals

[edit]

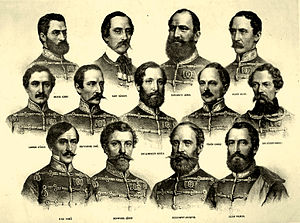

The 13 Martyrs of Arad, lithography by Miklós Barabás

- Lajos Aulich (1793–1849)

- János Damjanich (1804–1849)

- Arisztid Dessewffy (1802–1849)

- Ernő Kiss (1799–1849)

- Károly Knezić (1808–1849)

- György Lahner (1795–1849)

- Vilmos Lázár (1815–1849)

- Károly Leiningen-Westerburg (1819–1849)

- József Nagysándor (1804–1849)

- Ernő Poeltenberg (1814–1849)

- József Schweidel (1796–1849)

- Ignác Török (1795–1849)

- Károly Vécsey (1807–1849)

Custom

[edit]Legend has it that while the revolutionary leaders were being executed, Austrian soldiers were drinking beer and arrogantly clinking their beer mugs together in celebration of Hungary's defeat. Hungarians therefore vowed not to clink glasses again while drinking beer for 150 years.[5][6][7]

In reality, however, there is no information regarding this event at all, and historians deem it unlikely to have happened.[5][6][7] Historian Róbert Hermann speculated that wine producers hoping to raise their profits were the ones who popularized the tradition.[5][6][7] While the Hungarians' vow supposedly expired on 6 October 1999, in practice, this tradition continues to be sporadically practiced today.[7]

Western European public reactions

[edit]Haynau was widely acclaimed throughout Western Europe “Hyena of Brescia” and “Hangman of Arad”[8]

His reputation for brutality had spread throughout western Europe. In Brussels, Haynau narrowly escaped mob violence. In London, he was attacked by some draymen from the Barclay & Perkins brewery who threw mud and dung at him and chased him down the Borough High Street, shouting "Down with the Austrian butcher!".

Londoners attacked Haynau

"At first, they tossed a bundle of straw or a bale of hay down from the attic, and the crowd surged forward with great uproar, pelting it with barley, all manner of refuse, and debris, while they began to prod it with brooms, etc. From all sides, the crowd shouted, 'Down with the Austrian butcher!' In response to this, Haynau and his companions broke through the angry throng and fled the factory, but to their misfortune, they found themselves confronted by a waiting crowd of around 500 people outside, mostly workers, coal heavers, street children, and even women, who, cursing and shouting, beat him, tore his coat from his back, and dragged him by his long yellow mustache along Bankside, which runs by the Thames. The general ran for his life until he finally reached a tavern, the George public house, where he rushed through the open door, much to the astonishment of the landlady, Mrs. Benfield, and hid under a bed. Fortunately for him, the old structure had many doors, and as the crowd pressed in behind him, breaking down door after door, they could not find him. They might have killed him if the terrified landlady had not sent a swift messenger for the police to the nearby Southwark station, from where, shortly thereafter, Inspector Squires arrived with several officers, who rescued Haynau from his precarious situation."[9]

Haynau had already been a figure of hatred in the English satirical press, but after the event, they published sarcastic caricatures of him on a daily basis.[10][11]

"After the scandal, Haynau immediately left the English capital, but before his departure, he thanked the local authorities for the protection they had provided him. When the Italian revolutionary, Giuseppe Garibaldi, visited England in 1864, he insisted on visiting the brewery to thank the draymen.[12]

"Haynau faced similar treatment in Brussels, where he was reproached for the whipping of women. In Paris, the government had to do everything to ensure his safety, as the Parisians organized in groups to search for him upon learning that Haynau was in the city. In contrast, he was celebrated in the conservative Berlin. After his return, the loyal leadership of Vienna elected him an honorary citizen of the city.[13]

References

[edit]- ^ János B. Szabó, "Hungary's War of Independence" Archived 2008-04-01 at the Wayback Machine, History Net

- ^ Encyclopedia of 1848 Revolutions Archived 1999-12-24 at the Wayback Machine, Ohio State University

- ^ "Új Forrás - 1998. 6.sz. Bona Gábor: A szabadságharc honvédsége". epa.oszk.hu.

- ^ "Hungary Commemorates 1848–1849 Heroes – Hungary Today". 6 October 2014. Archived from the original on 2017-05-04. Retrieved 2015-06-27.

- ^ a b c Zrt, HVG Kiadó (October 6, 2006). "Miért nem koccint a magyar sörrel?". hvg.hu.

- ^ a b c Dániel, Rudolf (July 30, 2021). "Sörrel nem koccintunk – de vajon tényleg a '48-as forradalom leverése miatt?". divany.hu.

- ^ a b c d Zsolt, Hanula (October 6, 2009). "160 éve nem koccint sörrel a magyar". index.hu.

- ^ Haynau megalázta a magyar főtiszteket, origo.hu

- ^ The attack of Haynau “Down with the Austrian butcher!” Archived 2015-04-02 at the Wayback Machine, hopbot.co

- ^ László Kürti, "The woman-flogger, General Hyena: Images of Julius Jacob von Haynau (1786-1853), Enforcer of Imperial Austria". International Journal of Comic Arts, Fall/Winter, 2014, 65-90.

- ^ Londoni munkások inzultálják Haynaut , mek.oszk.hu

- ^ Flanders, Judith (July 2014). The Victorian City. New York, NY: St Martin's Press. p. 345. ISBN 978-1-250-04021-3.

- ^ The humbling of “General Hyena” 1850 - dawlish chronicles, dawlishchronicles.com