Mary Allen Wilkes

Mary Allen Wilkes | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | September 25, 1937 (age 87) |

| Alma mater | Wellesley College, Harvard Law School |

| Known for | Work with LINC computer |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Computer Programming, Logic Design, Law |

| Institutions | MIT, Washington University in St. Louis |

Mary Allen Wilkes (born September 25, 1937 in Chicago, Illinois) is a former computer programmer and logic designer, most known for her work with the LINC computer, now recognized by many as the world's first "personal computer".[1][2][3][4]

Career

Wilkes graduated from Wellesley College in 1959 where she majored in philosophy and theology.[5] Initially, Wilkes planned to be lawyer, but was discouraged by friends and mentors from pursuing law because of the challenges women faced in the field.[6] A geography teacher in the eighth grade had told Wilkes, "Mary Allen, when you grow up, you ought to be a computer programmer." [7] She worked in the field as one of the first programmers for a number of years before pursuing law and becoming an attorney in 1975.[8]

MIT

Wilkes worked under Oliver Selfridge and Benjamin Gold on the Speech Recognition Project at MIT's Lincoln Laboratory in Lexington, Massachusetts from 1959 to 1960, programming the IBM 704 and the IBM 709.[9] She joined the Digital Computer Group, also at Lincoln Laboratory, just as work was beginning on the LINC design under Wesley A. Clark in June 1961. Clark had earlier designed Lincoln's TX-0 and TX-2 computers. Wilkes's contributions to the LINC development included simulating the operation of the LINC during its design phase on the TX-2,[9] designing the console for the prototype LINC and writing the operator's manual for the final console design.[10]

In January, 1963, the LINC group left Lincoln Laboratory to form the Center for Computer Technology in the Biomedical Sciences at MIT's Cambridge, Massachusetts campus, where, in the summer of 1963 it trained the first participants in the LINC Evaluation Program, sponsored by the National Institutes of Health.[11] Wilkes taught participants in the program and wrote the early "LAP" (LINC Assembly Program) assembly programs for the 1024-word LINC. She also co-authored the LINC's programming manual, Programming the LINC with Wesley A. Clark.[12]

Washington University

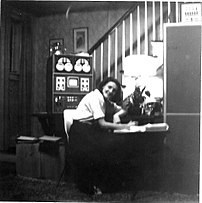

In the summer of 1964 a core group from the LINC development team left MIT to form the Computer Systems Laboratory at Washington University in St. Louis.[13] Wilkes, who had spent 1964 traveling around the world, rejoined the group in late 1964, but lived and worked from her parents' home in Baltimore until late 1965. She worked there on a LINC provided by the Computer Systems Laboratory and is usually considered to be the first user of a personal computer in the home.[14] Photos were shown of this at the 10th Vintage Computer Festival at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California, in November, 2007.[15]

By 1965 the LINC team had doubled the size of the LINC memory to 2048 12-bit words, which enabled Wilkes, working on the LINC at home, to develop the more sophisticated operating system, LAP6. LAP6 incorporated a scroll editing technique which made use of an algorithm proposed by her colleagues, Mishell J. Stucki and Severo M. Ornstein.[16] LAP6, which has been described as "outstandingly well human engineered",[17] provided the user the ability to prepare, edit, and manipulate documents (usually LINC programs) interactively in real time, using the LINC's keyboard and display, much like later personal computers. The LINC tapes performed the function of the scroll, and also provided interactive filing capabilities for documents and programs. Program documents could be converted to binary and run. Users could integrate their own programs with LAP6 using a link provided by the system, and swap the small LINC tapes around to share programs, an early "open source" capability.

The Computer Systems Laboratory's next project, also headed by Clark, was the design of "Macromodules", computer building blocks.[18] Wilkes designed the multiply macromodule, the most complex of the set.

Law career

Wilkes left the computer field in 1972 to attend the Harvard Law School. She practiced as a trial lawyer for many years, both in private practice and as head of the Economic Crime and Consumer Protection Division of the Middlesex County District Attorney's Office in Massachusetts. She taught in the Trial Advocacy Program at the Harvard Law School, 1983-2011, and sat as a judge for the school's first- and second-year Ames (moot court) competition for 18 years. In 2001 she became an arbitrator for the American Arbitration Association, sitting primarily on cases involving computer science and information technology. From 2005 through 2012 she served as a judge of the Annual Willem C. VIS International Commercial Arbitration Moot competition in Vienna, Austria, organized by Pace University Law School.

Notability

She is noted in the field of Computer Science for:

- Design of the interactive operating system LAP6 for the LINC, one of the earliest such systems for a personal computer.

- Being the first person to use a personal computer in the home.

Her work has been recognized in Great Britain's National Museum of Computing's 2013 exhibition "Heroines of Computing" at Bletchley Park, and by the Heinz Nixdorf MuseumsForum in Paderborn, Germany, in its 2015-16 exhibition, Am Anfang war Ada: Frauen in der Computergeschichte (In the beginning was Ada: Women in Computer History).

Quotes

- "I'll bet you don't have a computer in your living room."[19]

- "Doubling a 1024-word memory produces another small memory."[20]

- "We had the quaint notion at the time that software should be completely, absolutely free of bugs. Unfortunately it's a notion that never really quite caught on."[15]

- "To promise the System is a serious thing."[21]

Selected publications

- "LAP5: LINC Assembly Program", Proceedings of the DECUS Spring Symposium, Boston, May 1966. (LAP5 was the "Beta" version of LAP6.)

- LAP6 Handbook, Washington Univ. Computer Systems Laboratory Tech. Rept. No. 2, May 1967.

- Programming the Linc, Washington Univ. Computer Systems Laboratory, 2nd ed., January 1969, with W. A. Clark.

- "Conversational Access to a 2048-word Machine", Comm. of the ACM 13, 7, pp. 407–14, July 1970. (Description of LAP6.)

- "Scroll Editing: an on-line algorithm for manipulating long character strings", IEEE Trans. on Computers 19, 11, pp. 1009–15, November 1970.

- The Case for Copyright, Washington Univ. Computer Systems Laboratory Technical Memo., May 1971.

- "China Diary", Washington Univ. Magazine 43, 1, Fall 1972. Describes the trip six American computer scientists (and their wives, including Wilkes) made to China for 18 days in July 1972 at the invitation of the Chinese government to visit and give seminars to Chinese computer scientists in Canton, Shanghai, and Peking.

References

- ^ Computer Pioneer Award • IEEE Computer Society to Wesley A. Clark for the "First Personal Computer", 1981, Computer.org. Retrieved 2015-07-27.

- ^ "How the Computer became Personal", John Markoff, NY Times, Aug. 19, 2001

- ^ Clark, Wesley A., "The LINC was Early and Small", Proceedings of the Association for Computing Machinery: History of the Personal Computer, Jan. 9-10, 1986, pp. 133-155. ACM-0-89791-176-8-1/86-0133.

- ^ Bell, C. Gordon, J. Craig Mudge, and John E. McNamara, Computer Engineering, Digital Press, 1978, p. 175.

- ^ Ornstein, Severo, Computing in the Middle Ages, AUTHORHOUSE, 2002, p. 106. ISBN 9781403315175

- ^ Thompson, Clive (13 February 2019). "The Secret History of Women in Coding". Nytimes.com. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- ^ 10th 10th Vintage Computer Festival Archived 2011-07-28 at the Wayback Machine". Vintage.org. Retrieved 2015-07-27.

- ^ "Mary Allen Wilkes Lawyer Profile - martindale.com". Martindale.com. Retrieved 2015-07-27.

- ^ a b Interview with Mary Allen Wilkes at the 10th Vintage Computer Festival, Nov. 4, 2007, Mountain View, CA. Retrieved 2015-07-27.

- ^ LINC Control Console, Washington Univ. Computer Systems Laboratory, LINC Document No. 2, July 23, 1963.

- ^ Rosenfeld, S.A ., Laboratory Instrument Computer (LINC): The Genesis of a Technological Revolution. In the proceedings of the Seminar in Celebration of the 20th Anniversary of the LINC Computer. NIH Rept., Office of NIH History, November 30, 1983, p. 4. history.nih.gov. Retrieved 2015-07-27.

- ^ Programming the LINC, Washington Univ. Computer Systems Laboratory, 2nd ed., January 1969, with W. A. Clark.

- ^ Rosenfield, op. cit., p. 5.

- ^ Ornstein, Severo and Bruce Damer, The LINC @ 45: A Paradigm Shift, in 1962, 2008. www.digibarn.com. Retrieved 2015-07-28.

- ^ a b Wilkes, Mary Allen, 10th Vintage Computer Festival Panel Presentation, Mountain View, CA, Nov. 5, 2007, minutes 28–40. Retrieved 2015-07-28.

- ^ Wilkes, Mary Allen, LAP6 Use of the Stucki-Ornstein Text Editing Algorithm, Washington Univ. Computer Systems Laboratory Tech. Rept. No. 18, February, 1970.

- ^ Denes, P. B., and M. V. Matthews, "Laboratory Computers: Their capabilities and how to make them work for you", Proceedings of the IEEE, vol. 58, no. 4, Apr. 1970, pp. 520-530, at 522.

- ^ Clark, W.A., et al., Macromodular Computer Systems (seven papers), AFIPS Spring Joint Computing Conference 1967, 335-401. Retrieved 2015-7-28.

- ^ Wilkes's father to countless friends and acquaintances in 1965. (See Interview with Mary Allen Wilkes at the 10th Vintage Computer Festival, Nov. 4, 2007, at footnote 8,)

- ^ Preface, LAP6 Handbook.

- ^ LAP6 Handbook, quoting Søren Kierkegaard, Philosophical Fragments.