Matsukaze

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2010) |

| Matsukaze | |

|---|---|

| 松風 | |

| English title | Wind in the Pines |

| Written by | Kanami |

| Revised by | Zeami Motokiyo |

| Category | 3rd — katsura mono |

| Mood | mugen |

| Style | furyū |

| Characters | shite Matsukaze tsure Murasame waki priest aikyōgen villager |

| Place | Suma-ku, Kōbe |

| Time | Autumn — Ninth month |

| Sources | Kokinshū, Senshusho |

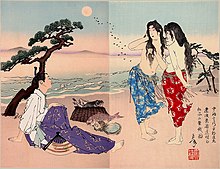

Matsukaze (松風, Wind in the Pines) is a play of the third category by Kanami, revised by Zeami Motokiyo. One of the most highly regarded of Noh plays, it is mentioned more than any other in Zeami's own writings,[1] and is depicted numerous times in the visual arts.

Plot

The two main characters are the lingering spirits of the sisters Matsukaze (Wind in the Pines) and Murasame (Autumn Rain), who once lived on the Bay of Suma in Settsu Province, where they ladled brine in order to make salt. A courtier, Middle Counsellor Ariwara no Yukihira, dallied with them during his exile to Suma for three years. Shortly after his departure, word of his death came and they died of grief. They linger on as spirits or ghosts, attached to the mortal world by their sinful (according to Buddhist doctrine) emotional attachment to mortal desires; this is a common theme in Noh.

The play opens with a traveling priest asking a local about a memorial he sees. The local explains that the memorial is to the two sisters. This is followed by a scene in which the sisters, ladling seawater into their brinecart at night, become fascinated by the sight of the moon in the water, and try to capture it.

The priest dreams that he meets them when asking for lodgings. After revealing their identities, they explain their past, and grow overcome with their love and longing for Yukihira. Matsukaze, after donning the courtly hunting robe and hat left her by the courtier, mistakes a pine for her love, and Murasame joins her briefly in madness, before recovering, passing on from the mortal world of emotional attachment, and leaving her sister behind.

Sources and themes

Royall Tyler and other scholars attribute the bulk of the work to Zeami, claiming that it is based on a brief dance piece by his father Kan'ami.[1] The play's contents allude strongly to elements of the Genji monogatari, particularly the chapters in which Hikaru Genji falls in love with a lady at Akashi and later leaves her. The early section written by Kan'ami quotes from the "Suma" chapter of the monogatari, the play's setting at Suma evokes these events and the theme of women of the shore who, after an affair with a high-ranking courtier, are left waiting for his return. The play also contains many allusions to the language of the monogatari, which would have been recognized by the poets of Zeami's day.[2]

The name of the chief character, and title of the play, Matsukaze, bears a poetic double meaning. Though Matsu can mean "pine tree" (松), it can also mean "to wait" or "to pine" (待つ). Matsukaze pines for the return of her courtier lover, like the woman of Akashi in the Genji, and like the woman in Zeami's play Izutsu. Tyler also draws a comparison between the names of the two sisters to a traditional element in Chinese poetry, referring to different strains of music as the Autumn Rain and the Wind in the Pines; Autumn Rain is strong and gentle intermittently, while the Wind in the Pines is soft and constant. Though the characters in the play actually represent the opposite traits – Matsukaze alternating between strong emotional outbursts and gentle quietness while her sister remains largely in the background, and acts as a mediating influence upon Matsukaze – the comparison is nevertheless a valid and interesting one.

Finally, Tyler offers the idea that the two women are aspects of a single psyche, or that they are "purified essences of human feeling... twin voices of the music of longing" [3] and not actually fully fleshed people.

Notes

- ^ a b Tyler 1992, p. 183.

- ^ Goff 1991, p. 65.

- ^ Tyler 1992, p. 191.