Nikolaus Storch

Nikolaus Storch (born pre-1500, died after 1536) was a weaver and radical lay-preacher in the Saxon town of Zwickau. He and his followers, known as the Zwickau Prophets played a brief role during the early German Reformation years in south-east Saxony, and there is a view that he was a forerunner of the Anabaptists. In the years 1520-1521, he worked closely with the radical theologian Thomas Müntzer.

Weaver and lay preacher

Very little is known about the life of Storch. There are no data about his place or date of birth, but he is assumed to be a native of Zwickau itself. His activities both in and away from Zwickau are not well-documented. He left no letters or other writings. He was a weaver by trade, but it is not known whether he was an apprentice or a master-weaver. Zwickau, at that time a town of around 7000 inhabitants, was a prosperous town with a significant cloth trade, with the burgeoning silver-mining operations in the surrounding Erzgebirge mountains. The influx of wealth from the mines meant that several local master-weavers had the capacity to break smaller competitors. This introduced volatile social and economic relationships into the town. The weavers’ religious organisation in Zwickau – the Fronleichnams-bruderschaft or ‘Brotherhood of Corpus Christi’ – had an altar at the church of St Katharine in the town. Prior to 1520, a splinter group broke away from this guild under Storch’s leadership, a sect whose members believed that the source of true Christian belief came through visions and dreams. Storch was remarkably well-read in the Bible, having been taught by Balthasar Teufel, one-time schoolmaster of Zwickau. Storch had made several trips to Bohemia in the line of business, and there had come under the influence of the Taborites of Zatec (Saatz). In Zwickau he conducted ‘corner sermons’ in the houses of other weavers. The town chronicler Peter Schumann thought of Storch as ‘someone with a profound knowledge of Scripture and expert in the things of the Spirit’ [1]

Working with Thomas Müntzer

When the radical reformer Thomas Müntzer was appointed to preach at St Katharine’s Church, in October 1520, after a short period at the neighbouring St Mary’s, he and Storch began to work together. Müntzer was greatly interested in Storch’s doctrines, although he viewed Storch as a like-minded individual, rather than a follower or someone to follow. During the winter of 1520-21, tensions in the town ran high between Catholics and reformers, plebeians and richer citizens, sects and town-council. A number of disturbances took place in the town, usually involving the lower classes and frequently resulting in acts of violence against the Catholic monks.

On 14 April 1521, a ‘Letter of the 12 Apostles and 72 Disciples’ was posted up in the town, addressed to the Lutheran/Humanist reformer Johann Sylvanus Egranus, who had crossed swords with Müntzer and Storch on several occasions already. Egranus was described now as the “desecrator and slanderer of God ... who hounds God’s servant ... a heretical rogue”. The letter was almost certainly the work of Storch’s group, but it defended both Storch and Müntzer jointly. It enumerated, in verse, all the false doctrines of Egranus, his denial of the suffering of the soul, his worship of the ‘world’ and of money, and his preference for the company of ‘bigwigs’ :

“And you seek mere chattles, cash and praise,

But that’s the last thing you’ll get from the 72 Disciples,

And just watch what you’ll get from the 12 Apostles,

And then even more from the Master...

And we want to prove in writing that you’re an arch-heretic”

[2]

In a defamatory letter of that same month, Müntzer was depicted thus: “at that time preacher at St Katharine’s, [he] made them [the Storchites] his supporters, won over the weavers, particularly one named Nichol Storch, whom he praised so mightily from the pulpit, raised him above all other priests as the only one who knew the Bible better and who was highly favoured by the Spirit...that Storch dared to give corner-sermons beside Thomas... Thus this Nichol Storch was favoured by Master Thomas; who recommended from the pulpit that laymen should be our prelates and priests”.[3] Although this same report talked of the ‘Storchite sect’, there is no indication that this included Müntzer: indeed, the report states that the ‘secta Storchitorum ... conspired and gathered together as Twelve Apostles and Seventy-Two other Disciples ... reinforced by Master Thomas and his followers’, which strongly suggests that there were two separate groupings.

In the event, the town-council retained enough authority in April to crack down on the unrest. Müntzer was forced to flee the town on 16 April, after yet another riot by Storch’s supporters, 56 of whom were put behind bars.

One of Müntzer’s friends, Markus Stübner (or Thoma) of Elsterberg, accompanied Müntzer on a journey to Prague, which lasted from late June until late November 1521; Stübner then returned to Saxony and teamed up with Storch.

After his departure from Zwickau in April 1521, Müntzer had no more dealings with Storch. In June 1521, he wrote to Mark Stübner wondering why Storch had not written to him. But his question is not shaded with any annoyance. His only other reference to Storch in later days was in a letter to Luther of July 1523: “You raise objections about Markus and Nicholas. What manner of men they are is up to them, Galatians 2... As to what they said to you, or what they have done, I know nothing about it”.[4] ‘Galatians 2’ is a quite telling reference: this tells the story of certain early Christians who, through lack of principle, drew back from arguments with the Jews. This judgement in 1523 indicates his doubts about Storch in the intervening period, and - with the man - his ideas.

Wittenberg

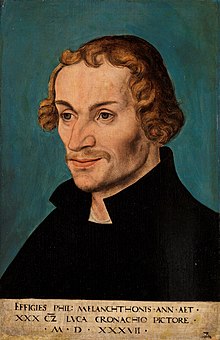

After the events of April, an uneasy peace settled over Zwickau which lasted until the end of the year. But in early December, the town-council summoned Storch and other members of his group to a hearing. The result of this being unfavourable, Storch left town. Nothing daunted, in mid-December 1521, he, along with Markus Stübner and Thomas Drechsel, turned up in Wittenberg to argue their interpretation of the reforms before the ‘official’ leaders. Luther was sitting at that time in the Wartburg Castle, whither he was spirited in April 1521 after the Imperial Diet at Worms, so it was left to his lieutenant Philipp Melanchthon and Nikolaus von Amsdorf to greet and debate with Storch, specifically on visions and baptism. Melanchthon’s immediate reaction was one of excitement, a feeling shared by several of his colleagues. However, caution reared its head, and he decided to seek advice from Electoral Prince Friedrich and from Luther. To Prince Friedrich he wrote on 27 December: “Your Highness is aware that many, various and dangerous dissensions have been awoken in Your Highness’ Zwickau... Three men, expelled by the authorities because of those disturbances, have come here, two of them common but literate weavers, the third an academic [Stübner]. I have listened to them; it is a wonder, but they sat down to preach, and said clearly that they had been sent by God to teach, that they spoke familiarly with God, that they could see the future; in short that they were prophets and apostles. How much I was moved by them, I cannot easily express. Certain things persuade me not to condemn them... No one other than Martin can judge them more closely...” [5]

In a covering note to Friedrich’s chaplain, Georg Spalatin, Melanchthon added: “The Holy Spirit is in these men...” The reaction of this leader of the Wittenberg movement was quite surprising; anyone without university training or a theological education was generally given short shrift; in later years, most unordained reformed preachers were regarded as ‘Anabaptists’. But in the last months of 1521, radicalism was rampant, and Wittenberg was open to suggestion.

Prince Friedrich’s reaction to Melanchthon’s letter was to despatch Spalatin to Wittenberg post-haste to interview the three ‘Zwickau Prophets’, and to warn Melanchthon against Storch, whereupon Melanchthon changed his tune, and expressed an interest only in the question of baptism.

Later life

Storch stayed for a while in Wittenberg and then moved on. It is suggested that he spent some years in the west of Thuringia, and Luther reported that he was active in Andreas Karlstadt’s town of Orlamünde in March of 1524. A warning was issued by the Nuremberg preacher Dominicus Sleupner to the Strasburg town-council who stated that Storch was in their town in December 1524. However, none of these three reports have been validated.

According to the chronicler Enoch Widmann, Storch was in the Bavarian town of Hof at the end of 1524, working as a weaver, but still preaching and gaining followers. Towards the end of January 1525, he applied to the mayor of Zwickau to be allowed to return to his home-town, but this was refused. There is a false report of his death in Munich at the end of 1525, but he was still being mentioned in the Zwickau town records of 1536 – therefore alive, and back in or around Zwickau. After that date, there is no further report of him.

Doctrines

A summary of Storch’s teachings in Zwickau was made in a letter, dated 18 December 1521, to Duke Johann of Saxony. The letter was probably written by the new Lutheran preacher at St Mary’s Church, Nikolaus Hausmann: “some men doubted whether the belief of the godfather can be of use in the baptism. And some think that they can be blessed without being baptised. And some state that the Holy Bible is not useful in the education of men, but that men can only be taught by the Spirit, for if God had wanted to teach men with the Bible, then He would have sent us a Bible down from heaven. And some say that one should not pray for the dead. And suchlike horrible abominations which are giving your Lordship’s town an unchristian and Picardish name.” [6]

In 1529, Melanchthon looked back to 1521 and described Storch’s doctrines: “God had shown him in dreams what He wanted. He claimed that an angel had come to him and had said that he would sit upon the throne of the Archangel Gabriel, and would thus be promised mastery over all the earth. He also said that saints and the Elect would reign after the destruction of the Godless, and that, under his leadership, all the kings and princes of the world would be killed and the Church would be cleansed. He arrogated to himself the judgment of souls, and claimed that he could recognise the Elect. He simply laughed about Mass, baptism and communion. He invented certain worthless tricks with which he intended to prepare men for the reception of the Spirit: if they spoke little, dressed poorly and ate poorly and together demanded the Holy Spirit of God...” [7]

The Lutheran Mark Wagner listed eight articles of faith proposed by Storch, which included: a condemnation of the ‘Christian’ institution of marriage, whilst propagating the idea that ‘anyone can take women whenever his flesh commands him...and live with them promiscuously as he wishes’; a call for the communalisation of property; an invective against secular and ecclesiastical authorities; arguments against infant baptism - but not, incidentally, in support of adult baptism; condemnation of the ceremonies of the Church; and a proclamation of Free Will in matters of faith.[8]

Legacy

In general, Storch was considered by commentators of the 16th century as a leading ‘Anabaptist’ However, there was a tendency to call almost any radical preacher an Anabaptist, with hindsight only and without distinction. Such classification therefore needs to be treated with caution.

He is credited with having established Anabaptism in central Germany, after the report by the Hof chronicler Widmann that he practised adult-baptism in the town of Hof.

He is also credited by Melanchthon (in a letter to Camerarius, 17 April 1525) with having played a leading role in the Peasants War of 1525. This supposition is entirely without foundation, and probably reflects Melanchthon’s continuing guilt about his waverings in 1521.

Notes

- ^ Peter Matheson (ed) - The Collected Works of Thomas Müntzer. (Edinburgh,1988) : 32

- ^ J.K.Seidemann - Thomas Müntzer. (Dresden,1842) : 110–112

- ^ J.K.Seidemann - Thomas Müntzer. (Dresden,1842)

- ^ Peter Matheson (ed) - The Collected Works of Thomas Müntzer. (Edinburgh,1988) : p.58

- ^ N. Müller - Die Wittenberger Bewegung 1521-1522, in: Archiv für Reformationsgeschichte, Vols 6 and 7, 1908

- ^ N. Müller - Die Wittenberger Bewegung 1521-1522, in: Archiv für Reformationsgeschichte, Vols 6 and 7, 1908 : 397–398

- ^ A.Bach - Philipp Melanchthon (Berlin,1963): p.164

- ^ P. Wappler - Thomas Müntzer in Zwickau und die ‘Zwickauer Propheten’. (Zwickau, 1908) : 81–86

Further reading

- A. Bach (1963). Philipp Melanchthon. Berlin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - R. Bachmann (1880). Niclas Storch, der Anfänger der Zwickauer Wiedertäufer. Zwickau.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - J. Camerarius (1566). De Philippi Melanchthonis ortu, totius vitae curriculo et morte ... narration. Leipzig.

- S. Hoyer (1984). "Die Zwickauer Storchianer - Vorläufer der Täufer?. In: Jahrbuch für Regionalgeschichte". 13/1984: 60–78.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - M. Krebs & H.-G. Rott (eds.) (1959). Quellen zur Geschichte der Täufer, Bd. 7, Elsass, Vol. 1. Gütersloh.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Peter Matheson, trans and ed: (1988). The Collected Works of Thomas Müntzer. Edinburgh. ISBN 0-56729-252-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - N. Müller (1908). "Die Wittenberger Bewegung 1521-1522". Archiv für Reformationsgeschichte. Vols 6 and 7.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - J.K.Seidemann (1842). Thomas Müntzer. Dresden.

- M. Wagner (1596). Einfeltiger Bericht, wie durch Nicolaum Storchen die auffruhr in Thuringen ... angefangen.

- P. Wappler (1908). Thomas Müntzer in Zwickau und die ‘Zwickauer Propheten’. Zwickau.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) (Reprinted: Gütersloh 1966). - P. Wappler (ed.) (1913). Die Täuferbewegung in Thüringen 1526-1584. Jena.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - E. Widmann (1894). Chronik von Hof, ed. by C. Meyer, Vol. 1.

External links

- Siegfried Hoyer: Storch, Nikolaus. In: Sächsische Biografie. Published by Institut für Sächsische Geschichte und Volkskunde, edited by Martina Schattkowsky.

- Christian Neff: Storch, Nikolaus (16th century) Storch, Nikolaus (16th century). In: Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online