Nimrod Expedition

The British Antarctic Expedition 1907–09, otherwise known as the Nimrod Expedition, was the first of three expeditions to the Antarctic led by Ernest Shackleton. It was financed without governmental or institutional support and relied on private loans and individual contributions. Its ship, Nimrod, was a 40-year-old small wooden sealer of 300 tons displacement,[1] and the expedition's members generally lacked relevant experience. Nimrod departed from British waters on 7 August, less than six months after Shackleton’s first public announcement of his plans.

Initially, the expedition's public profile was much lower than that of Scott’s Discovery Expedition six years earlier. However, nationwide interest was aroused by the news of its achievements. The South Pole was not attained, but the expedition’s southern march reached a farthest south latitude at 88°23′S, and it could thus claim that it had got within a hundred miles of the Pole.[2] This was by far the longest southern polar journey to that date and a record convergence on either Pole. During the expedition a separate group led by Welsh-born Australian geology professor Edgeworth David reached the estimated location of the South Magnetic Pole, and the first ascent was made of Mount Erebus, the lofty Ross Island active volcano. The scientific team, which included the future Australian Antarctic Expedition leader Douglas Mawson, carried out extensive geological, zoological and meteorological work. Shackleton’s transport arrangements, based on Manchurian ponies, motor traction, and sledge dogs, were innovations which, despite limited success, were later copied by Scott for his ill-fated Terra Nova Expedition.

The expedition was a public triumph, although in the eyes of some of the London geographical establishment its successes were compromised because Shackleton had broken a promise to Scott that he would not base his winter quarters in or near McMurdo Sound. Scott had claimed personal, exclusive rights to work in this area, where the Discovery Expedition had wintered in 1902 and 1903. Shackleton had agreed under duress to avoid the Sound, but ice conditions ultimately forced Nimrod to land there. This further soured relations between the two men (who nevertheless maintained public civilities) and caused the complete rupture of Shackleton’s formerly close friendship with Edward Wilson.

On his return, Shackleton survived the Royal Geographical Society's scepticism about his achievements and received many public honours, including a knighthood from King Edward VII. He made little financial gain from the expedition and eventually depended on a government grant to cover its liabilities. Within three years his farthest south record had been surpassed, as first Amundsen and then Scott reached the South Pole. In his own moment of triumph, Amundsen recognized: "Sir Ernest Shackleton's name will always be written in the annals of Antarctic exploration in letters of fire".[3]

Origins

Shackleton, a junior officer on Captain Scott's Discovery Expedition, was sent home from the Antarctic in 1903 after a physical collapse during the expedition's main southern journey.[4] Scott’s verdict was that he "ought not to risk further hardships in his present state of health".[5] Shackleton was disappointed, and regarded this as a personal stigma;[6] on his return to England he was determined to prove himself,[7] although his future was unclear. He declined the opportunity of a swift Antarctic return as chief officer of Discovery's relief ship Terra Nova, after helping to fit her out; he also helped to equip Uruguay, the ship being prepared for the relief of Otto Nordenskjold’s stranded expedition.[8] During the next few years, while nursing intermittent hopes of resuming his Antarctic career, he pursued other options, and in 1906 he was working for the industrial magnate Sir William Beardmore as a public relations officer.[9]

According to biographer Roland Huntford, what stung Shackleton into positive action were the references to his physical breakdown in Scott’s The Voyage of the Discovery, published in 1905.[10] He then began drawing up a programme for his own Antarctic expedition and looking for potential backers. His initial plans appear in an unpublished document dated early 1906[11] and include a cost estimate of GB£17,000 for the entire expedition (equivalent to about £850,000 in 2008).[11] At this stage he had no financial backing, and it was not until early 1907 that his employer, Beardmore, offered a £7,000 loan guarantee.[12] With this in hand, Shackleton felt confident enough to announce his intentions to the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) on 12 February 1907.[13]

Preparations

Initial plans

Shackleton’s original unpublished plan was to base himself at the old Discovery Expedition headquarters in McMurdo Sound and from there mount attempts on the geographical South Pole and the South Magnetic Pole. Other journeys and continuous scientific work would follow.[11] This early plan also revealed Shackleton’s proposed transport methods: the use of dogs, ponies and a specially designed motor vehicle. Neither ponies nor motor traction had been used in the Antarctic before.[14] By the time he announced his plans to the RGS in February 1907. Shackleton had revised his cost estimate to a more realistic £30,000 (2008: £1.5 million).[15] However, the response of the RGS to his plans was at best lukewarm; Shackleton would learn later that the Society was by now aware of Captain Scott’s wish to lead a new expedition and that it wanted to reserve its full approval for Scott.[15]

Nimrod

Shackleton intended to arrive in Antarctica in January 1908 and would have to leave England during the 1907 summer. He had just six months to acquire and fit out a ship, obtain all the equipment and supplies, recruit the personnel and, above all, obtain the financing, none of which was yet secured beyond Beardmore’s guarantee. Shackleton travelled to Norway intending to buy a 700–ton polar vessel, Bjorn, that would have served ideally as an expedition ship, but she was beyond his means.[16] He had to settle for the elderly, much smaller Nimrod, which he was able to acquire for £5,000 (2008: £250,000).[17][18]

Shackleton was shocked by his first sight of Nimrod after her arrival in London from Newfoundland in June 1907. "She was much dilapidated and smelt strongly of seal oil, and an inspection […] showed that she needed caulking and that her masts would have to be renewed."[17] However, in the hands of experienced ship-fitters she soon "assumed a more satisfactory appearance".[17] Later, Shackleton reported, he became extremely proud of the sturdy little ship.[17]

Raising finances

By early July 1907, Shackleton had secured little backing beyond Beardmore’s guarantee and lacked the funds to complete the refit of the ship.[19] In mid-July he approached the philanthropic Earl of Iveagh,[20] who agreed to guarantee the sum of £2,000 provided that Shackleton found others to bring the amount to £8,000. He was able to do this, the extra funds including £2,000 from Sir Philip Brocklehurst, who paid this sum to secure a place on the expedition.[19]

A last-minute gift of £4,000 from Shackleton's cousin William Bell[21] still left the expedition far short of the required £30,000 but enabled Nimrod to sail south, after inspection by King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra, on 11 August 1907.[22] A further £5,000 was provided as a gift from the Government of Australia, and the New Zealand Government gave £1,000.[23] By these means, and with other smaller loans and donations, the £30,000 was raised, although by the end of the expedition total costs had risen, by Shackleton's estimate, to £45,000.[24][25]

Shackleton expected to make large sums from his book about the expedition and from lectures. He also hoped to profit from sales of special postage stamps bearing the cancellation stamp of the Antarctica post office that Shackleton, appointed temporary postmaster, intended to establish. None of these schemes produced the anticipated riches, although the post office was set up at Cape Royds and used as a conduit for the expedition's mail.[26][27]

Personnel

Hoping to recruit a strong contingent from the Discovery Expedition, Shackleton offered his friend Edward Wilson the post of chief scientist and second-in-command. Wilson refused, ostensibly on the grounds of his work with the Board of Agriculture’s Committee on the Investigation of Grouse Disease.[28] Further refusals followed from former Discovery colleagues Michael Barne, Reginald Skelton and finally George Mulock, who inadvertently revealed to Shackleton that the Discovery officers had all committed themselves to Scott and his as yet unannounced expedition.[28][29] From the Discovery Shackleton was able to secure the services only of two Petty Officers, Frank Wild and Ernest Joyce.[30]

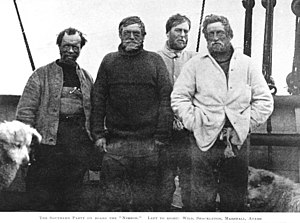

Shackleton’s second-in-command—although this was not clarified until the expedition reached the Antarctic—was Jameson Boyd Adams, a Royal Naval Reserve lieutenant who had turned down the chance of a regular commission to join Shackleton.[31] He would also act as the expedition’s meteorologist. Nimrod's captain was another naval reserve officer, Rupert England, with John King Davis, who would later make a great reputation in the Antarctic, as chief officer.[32] Aeneas Mackintosh, a Merchant navy officer from the P and O shipping line, was appointed second officer, later transferring to the shore party.[23] Also destined for the shore party were the two surgeons, Alistair McKay and Eric Marshall, Bernard Day the motor expert, and Sir Philip Brocklehurst, the subscribing member who had been taken on as assistant geologist.[33]

The small scientific team that departed from England[34] was greatly strengthened by two additions from Australia. The first of these was Tannatt William Edgeworth David, a professor of geology at the University of Sydney.[23][35] The second was a former pupil of David’s, Douglas Mawson, a lecturer in mineralogy at the University of Adelaide. Both had originally intended to sail to Antarctica and then immediately back with Nimrod but were persuaded to become full members of the expedition. Each made important contributions to the expedition's scientific achievements, and David was also influential in securing the Australian government’s £5,000 grant.[23]

Before departure for the Antarctic in August 1907 Joyce and Wild took a crash course in printing, as it was Shackleton's intention to publish a book or magazine while in the Antarctic.[36]

Promise to Scott

Shackleton’s February 1907 announcement that he intended to base his expedition at the old Discovery headquarters was noted by Captain Scott, who immediately wrote to Shackleton claiming priority rights to McMurdo Sound. "I feel I have a sort of right to my own field of work", wrote Scott. He added: "... anyone who has had to do with exploration will regard this region primarily as mine", and concluded by reminding Shackleton of his duty of loyalty towards his former commander.[37]

Shackleton’s initial reply was accommodating: "I would like to fall in with your views as far as possible without creating a position that would be untenable to myself".[37] However, Edward Wilson, asked by Shackleton to mediate, took an even tougher line than Scott. "I think you should retire from McMurdo Sound", he wrote, advising Shackleton not to make any plans to work from anywhere in the entire Ross Sea quarter until Scott decided "what limits he puts on his own rights".[37] This was too much for Shackleton, who replied: "There is no doubt in my mind that his rights end at the base he asked for [...] I consider I have reached my limit and I go no further".[37]

The matter was unresolved when Scott returned from sea duty in May 1907. Scott pressed for a line of demarcation at 170°W—everything to the west of that line, including Ross Island, McMurdo Sound, and Victoria Land, would be Scott’s preserve. Shackleton, with other concerns pressing on him, felt obliged to concede. On 17 May he signed a declaration stating that "I am leaving the McMurdo base to you"[37] and that he would seek to land further west, either at the Barrier Inlet or at King Edward VII Land. He would not touch the coast of Victoria Land at all.[37] It was a capitulation to Scott and Wilson, and meant forfeiting the expedition's aim of reaching the South Magnetic Pole, located within Victoria Land.[37] To quote polar historian Beau Riffenburgh, it was "a promise that should never ethically have been demanded and one that should never have been given, impacting as it might on the entire safety of Shackleton’s expedition".[37]

In his own account of the expedition Shackleton makes no reference to the wrangle with Scott. He merely states that "before we finally left England I had decided that if possible I would establish my base in King Edward VII Land instead of [...] McMurdo Sound".[13]

Expedition

Voyage south

Nimrod left British waters in August 1907, while Shackleton and other expedition members followed later on a faster ship. The entire complement came together in New Zealand, ready for the ship's departure to Antarctica on New Year’s Day, 1908. As a means of conserving fuel, Shackleton had arranged with the New Zealand government for Nimrod to be towed to the Antarctic circle, a distance of approximately 1,650 miles (2,750 km),[38] the costs being shared by the government and the Union Steam Ship Company.[39] On 14 January, in sight of the first icebergs, the towline was cut.[39] Nimrod, under her own power, proceeded southward into the floating pack ice, heading for the Barrier Inlet where six years earlier Discovery had paused to allow Scott and Shackleton to take experimental balloon flights.[40]

The Barrier was sighted on 23 January, but the inlet had disappeared; the Barrier edge had changed significantly in the intervening years, and the section which had included the inlet had broken away to form a considerable bay—the Bay of Whales.[41][42] Shackleton was not prepared to risk wintering on a Barrier surface that might calve into the sea, so he turned the ship towards King Edward VII Land. After several efforts to approach this coast had failed, and with rapidly moving ice threatening to trap the ship, Nimrod was forced to retreat. Shackleton’s only choice now, other than abandonment, was to break the promise he had given to Scott. On 25 January he ordered the ship to head for McMurdo Sound.[41]

Cape Royds

Establishing the base

On arriving in McMurdo Sound on 29 January 1908, Nimrod’s progress southward to the Discovery base at Hut Point was blocked by frozen sea. Shackleton decided to wait a few days in the hope that the ice would break up. During this delay, second officer Aeneas Mackintosh suffered an accident that led to the loss of his right eye. After emergency surgery by Marshall and McKay, he was forced to relinquish his shore party place and go back to New Zealand with Nimrod. He recovered sufficiently to return with the ship in the following season.[43]

On 3 February Shackleton decided not to wait for the ice to shift but to make his headquarters at the nearest suitable landing place, Cape Royds. Late that evening the ship was moored, and a suitable site for the expedition’s prefabricated hut was selected.[44] The site was 20 miles (32 km) north of Hut Point—extra distance that would have to be covered on next season's main polar march.

During the following days the landing of stores and equipment took place. This effort was hampered by poor weather and by the caution of Captain England, who frequently took the ship out into the bay until ice conditions at the landing ground were in his view safer.[45] The next fortnight followed this pattern, leading to sharp disagreements between Shackleton and the captain. At one point Shackleton asked England to stand down on the grounds that he was ill, but England refused. The task of unloading became "mind-numbingly difficult"[45] but was finally completed on 22 February. Nimrod at last sailed away north, England unaware that ship’s engineer Harry Dunlop was carrying a letter from Shackleton to the expedition’s New Zealand agent, ordering a replacement captain for the return voyage.[46]

Ascent of Mount Erebus

After Nimrod's departure, the sea ice which had prevented it from proceeding south also departed, cutting off the party's route to the Barrier and thus making preparatory sledging and depot-laying impossible. Shackleton decided to give the expedition impetus by ordering an immediate attempt to ascend Mount Erebus.[47]

This mountain, 12,450 feet (3,790 m) high, had never been climbed. A party from Discovery (which had included Frank Wild and Ernest Joyce) had explored the foothills in 1904 but had not ascended higher than 3,000 feet (910 m).[47] Neither Wild nor Joyce was in the Nimrod Expedition’s Erebus party, which consisted of Edgeworth David, Douglas Mawson and Alistair McKay, with Marshall, Adams and Brocklehurst in support. The ascent began on 5 March.[47]

On 7 March, the main and support groups combined at around 5,500 feet (1,700 m), and all advanced towards the summit. On the following day a blizzard held them up, but early on 9 March the climb resumed; later that day the summit of the lower, main crater, was achieved.[47] By this time Brocklehurst’s feet were too frostbitten for him to continue, so he was left in camp while the others advanced to the active crater, which they reached after four hours. Several meteorological experiments were carried out, and many rock samples were taken. Thereafter a rapid descent was made, mainly by sliding down successive snow-slopes. The party reached the Cape Royds hut "nearly dead", according to Eric Marshall, on 11 March.[47]

Winter 1908

The expedition’s hut, a prefabricated structure measuring 33 x 19 feet (10m x 5.8m), was ready for occupation by the end of February. It was divided into a series of mainly two-person cubicles, with a kitchen area, a darkroom, storage and laboratory space. The ponies were housed in stalls built on the most sheltered side of the hut, while the dog kennels were placed close to the porch.[48] Shackleton's inclusive leadership style, in contrast to that of Scott, meant no demarcation between upper and lower decks—all lived, worked and ate together. Morale was high; as assistant geologist Philip Brocklehurst recorded, Shackleton "had a faculty for treating each member of the expedition as though he were valuable to it".[49]

In the ensuing months of winter darkness Joyce and Wild printed around 30 copies of the expedition’s book, Aurora Australis, which were sewn and bound using packaging materials.[50] The most important winter’s work, however, was preparing for the following season’s major journeys, which included attempts on both the South Pole and the South Magnetic Pole—by making his base in McMurdo Sound Shackleton had been able to reinstate the Magnetic Pole as an expedition objective. The prospects for the South Pole journey suffered a serious setback during the winter, when four of the remaining eight ponies died,[51] mainly from eating volcanic sand for its salt content.[47]

Southern journey

Outward march

Shackleton’s choice of a four-man team for the southern journey to the South Pole was largely determined by the number of surviving ponies. Influenced by his experiences on the Discovery Expedition, he had put his confidence in ponies rather than dogs for the long polar march.[52] The motor car, which ran well on flat ice, could not cope with Barrier surfaces and was not considered for the polar journey.[53] The men chosen by Shackleton to accompany him were Marshall, Adams and Wild. Joyce, whose Antarctic experience exceeded all save Wild’s, was excluded from the party after Marshall’s medical examination raised doubts about his fitness.[54]

The march began on 29 October 1908. Shackleton had calculated the return distance to the Pole as 1,718 miles (2,765 km). His initial plan allowed 91 days for the return journey, requiring a daily average distance of about 19 miles (31 km).[55] After a slow start due to a combination of poor weather and lameness in the horses, Shackleton reduced the daily food allowance to extend the total available journey time to 110 days. This required a shorter daily average of around 15 miles (24 km).[56] Between 9 November and 21 November they made good progress, but the ponies suffered on the difficult Barrier surface, and the first of the four had to be shot when the party reached 81°S. On 26 November a new farthest south record was established as they passed the 82°17′ mark set by Scott’s southern march in December 1902.[57] Shackleton’s party covered the distance in 29 days compared with Scott’s 59, using a track considerably east of Scott's to avoid the surface problems he had encountered.[58]

As the group moved into unknown territory, the Barrier surface became increasingly disturbed and broken; two more ponies succumbed to the strain. The mountains to the west curved round to block their path southward, and the party's attention was caught by a "brilliant gleam of light" in the sky ahead.[59] The reason for this phenomenon became clear on 3 December when, after a climb through the foothills of the mountain chain, they saw before them "an open road to the south, [...] a great glacier, running almost south to north between two huge mountain ranges".[60] The reflection of the glacier's surface had caused the huge ice blink previously observed in the sky.

Shackleton later christened this glacier the "Beardmore" after the expedition's biggest sponsor. Travel on the glacier surface proved to be a trial, especially for Socks the pony, who had great difficulty in finding secure footings. On 7 December Socks disappeared down a deep crevasse, very nearly taking Wild with him. Fortunately for the party, the pony's harness broke, and the sledge containing their supplies remained on the surface. However, for the rest of the southward journey and the whole of the return trip they had to rely on man-hauling (pulling the sledges themselves).

At this point, personal antagonisms emerged. Wild privately expressed the wish that Marshall would "fall down a crevasse about a thousand feet deep".[61] Marshall wrote that following Shackleton to the Pole was "like following an old woman. Always panicking".[62] However, Christmas Day was celebrated with crème de menthe and cigars. Their position was 85°51′S, still 290 miles (470 km) from the Pole, and they were now carrying barely a month's supply of food, having stored the rest in depots for their return journey.[62] They could not cover the remaining distance to the Pole and back with this amount of food.[63] However, Shackleton was not yet prepared to admit that the Pole was beyond them and decided to go forward after cutting food rations and dumping all but the most essential equipment.[64]

On Boxing Day the glacier ascent was at last completed, and the march on the polar plateau began. Conditions did not ease, however. Shackleton recorded 31 December as the "hardest day we have had".[65] On the next day he noted that, having attained 87°6½′S, they had beaten North and South polar records.[66] That day Wild wrote that "if we only had Joyce and Marston here instead of those two grubscoffing useless beggars (Marshall and Adams) we would have done it (the Pole) easily".[67] On 4 January Shackleton finally admitted defeat, and revised his goal to the symbolic achievement of getting within 100 geographical miles (116&;statute miles, 187 km) of the Pole.[68] The party struggled on, at the borders of survivalnbsp,[69] until on 9 January 1909, after a last dash forward without the sledge or other equipment, the march ended. "We have shot our bolt", wrote Shackleton, "and the tale is 88°23′S".[70] They were 97 geographical miles from the South Pole.[2] The British flag was duly planted, and Shackleton named the polar plateau after King Edward VII.[71]

Return journey

The party turned for home after 73 days' travel. Rations had been cut several times to extend the journey time beyond the original 110-day estimate. Shackleton now aimed to reach Hut Point by 1 March, the date on which, according to Shackleton's prior orders, Nimrod would sail north. The condition of the party by now was that of "physical wrecks".[72] Yet, during the days following their turn northwards, they achieved impressive distances—22.5 miles (36 km) on 17 January, 26 miles (42 km) on the following day and 29 miles (47 km) on the 19th.[72] On the next day they reached the head of the glacier and began the descent. They had five days' food at half rations to last them until the Lower Glacier depot;[72] during the ascent the same distance had taken 12 days. Shackleton's physical condition was by now a major concern, yet according to Adams "the worse he felt, the harder he pulled".[72]

The depot was reached on 28 January. Wild, ill with dysentery, was unable to pull or to eat anything but biscuits, which were in short supply. On 31 January Shackleton forced his own breakfast biscuit on Wild, a gesture that moved Wild to write: "BY GOD I shall never forget. Thousands of pounds would not have bought that one biscuit".[73] A few days later the rest of the party were struck with severe enteritis, the result of eating tainted pony-meat. But the pace of march had to be maintained; the small amounts of food carried between depots would make any delay fatal. Fortunately a strong wind behind them enabled them to set a sail and maintain a good marching rate.[72]

"We are so thin that our bones ache as we lie on the hard snow", wrote Shackleton.[74] From 18 February onward they began to pick up familiar landmarks, and on the 23rd they reached Bluff Depot, which to their great relief had been copiously resupplied by Ernest Joyce. The range of delicacies over and above the crates of regular supplies was listed by Shackleton: "Carlsbad plums, eggs, cakes, plum pudding, gingerbread and crystallised fruit".[75] Wild's laconic comment was "Good old Joyce".[76]

Their food worries were now resolved, but they still had to get back to Hut Point before the 1 March deadline. The final leg of their march was interrupted by a blizzard, which held them in camp for 24 hours. On 27 February, when they were still 33 miles (55 km) from safety, Marshall collapsed. Shackleton then decided that he and Wild would make a dash for Hut Point in hopes of finding the ship and holding her until the other two could be rescued. They reached the hut late on 28 February.[77] Hoping that the ship was nearby, they sought to attract its attention by setting fire to a small wooden hut used for magnetic observations.[78] Shortly afterwards Nimrod, which had been anchored at the Glacier Tongue, came into view: "No happier sight ever met the eyes of man", wrote Wild later.[78] It was a further three days before Adams and Marshall could be picked up from the Barrier, but by 4 March the whole southern party was aboard and Shackleton was able to order full steam towards the north.[78]

Northern Party

During September 1908, while preparing for his southern journey, Shackleton gave instructions to Edgeworth David to lead a Northern Party to Victoria Land to carry out magnetic and geological work. The main aims, given in Shackleton's written orders, were to try to reach the Magnetic Pole and to carry out a thorough geological survey in the Dry Valley area.[79] David's party consisted of himself, Douglas Mawson and Alistair McKay. It would be a man-hauling party; the dogs remained at base to be used for depot-laying and other routine work.[80] The party had orders to plant the Union Jack at the Magnetic Pole and to take possession of Victoria Land for the British Empire.[81] After several days' preparatory work they started out on 5 October, drawn for the first few miles by the motor car.[82]

Due to sea ice conditions and adverse weather, progress was initially very slow. By the end of October they had advanced only 60 miles (100 km) up the difficult Victoria Land coast, and they decided to abandon all objectives save that of the Magnetic Pole.[83] It took more than a further month of travel and the traversing of the Nordenskjold Ice Tongue and the treacherous Drygalski Glacier before they were able to turn north-west towards the Pole's presumed location. Before then, David had a narrow escape after falling into a crevasse but was rescued by Mawson.[84]

Their way up to the inland plateau was via a labyrinthine glacier (later named the Reeve Glacier), which brought them on 27 December to a hard snow surface.[85] This enabled them to move more swiftly, at a rate of some 10 or 11 miles (17 km) daily, taking regular magnetic observations. On 16 January these observations showed them to be about 13 miles (21 km) from the Magnetic Pole. The next day, 17 January 1909, they reached their goal, at 72°15′S 155°16′E / 72.250°S 155.267°E, at an elevation of 7,260 feet (2,210 m). Following instructions, David took formal possession of the area for the British Empire.[85]

Exhausted, and short of food, the party faced a return journey of 250 miles (400 km) in just 15 days to meet their prearranged coastal rendezvous with Nimrod. Despite increasing physical weakness, they maintained their daily distances until, on 31 January, a poor choice of route on the final stages left them 16 miles (26 km) from where Nimrod was to retrieve them. Bad weather delayed them further, and the rendezvous was not reached until 2 February. That night, in heavy drifting snow, Nimrod passed by them, unable to make out their camp.[85] Two days later, however, after Nimrod had turned south again, the group was spotted. In the rush to reach the ship Mawson fell 18 feet (5.5 m) down a crevasse and was fortunate to survive. The party had been travelling for four months and were wearing the same clothes in which they had departed Cape Royds, and aboard ship "the aroma was overpowering".[86] Before this rescue, Nimrod had picked up a geological party consisting of Priestley, Brocklehurst and Bertram Armytage, who had been carrying out geological work in the Ferrar Glacier region.[86]

Aftermath

On 23 March 1909, Shackleton landed in New Zealand and cabled a 2,500-word report to the London Daily Mail, with whom he had an exclusive contract.[87] Amid the acclamation and unstinting praise that Shackleton received from the exploring community, including Nansen and Amundsen, the response of the Royal Geographical Society was more guarded. Its former president, Sir Clements Markham, privately expressed his disbelief of Shackleton's claimed latitude.[88] However, on 14 June, Shackleton was met at London's Charing Cross Station by a very large crowd, which included not only RGS president Leonard Darwin but also a reluctant Captain Scott.[89] Whatever Scott's private feelings towards Shackleton, they did not stop him adopting his rival's transport strategy for his next expedition.[90]

As to the latitude claimed, the only reason for doubting its accuracy was that after 3 January all computations of position were based on dead reckoning; that is, on course, speed and elapsed time. The position on 3 January had been fixed by observation at 87°22′. Shackleton's table of distances showed daily averages of around 15 miles (24 km) for the following days. On 9 January 1909 the table showed that the party travelled 18 miles (29 km) in five hours to reach their farthest south and the same distance back in another five hours.[91] This far exceeded travel speeds attained during any other stage of the journey. But it was a dash, "half running, half walking", unencumbered by the sledge or other equipment.[92] Each of the four men independently confirmed his belief in the latitude achieved, and none gave any subsequent cause for his word to be doubted.[93]

Official recognition soon came to Shackleton in the form of the rank of Commander of the Royal Victorian Order bestowed by the King, who later conferred a knighthood.[94] The RGS presented him with a gold medal, although apparently with reservations—"We do not propose to make the Medal so large as that which was awarded to Captain Scott", recorded an official.[95] Although in the eyes of the public he was a hero, the riches that Shackleton had anticipated failed to materialise. The soaring costs of the expedition and the need to meet loan guarantees meant that he was saved from financial embarrassment only by a belated government grant of £20,000.[95]

The farthest south record of the Nimrod Expedition stood for less than three years, until Amundsen reached the South Pole on 15 December 1911. Shackleton could still bask in Amundsen's fulsome tribute to him: "What Nansen is to the North, Shackleton is to the South".[96] Thereafter his Antarctic ambitions were fixed on a transcontinental crossing, which he attempted, unsuccessfully, with the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1914–17. His status as a leading figure of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration was assured, however. Other members of the Nimrod Expedition also achieved fame and standing in future years. Edgeworth David, Adams, Mawson and Priestley all eventually received knighthoods, the latter two continuing their polar work on further expeditions, though neither went south again with Shackleton.[97] Frank Wild was second-in-command to the "Boss" on his two subsequent Antarctic ventures and took command of the Quest after Shackleton's death in South Georgia in 1922.[98] Nimrod's fate, 10 years after its return from the Antarctic, was to be battered to pieces in the North Sea, after running aground on the Barber Sands off the Norfolk (U.K.) coast on 31 January 1919. Only two of her 12–person crew survived.[99]

See also

Notes and references

- ^ 300 tons is the long ton weight; metric equivalent 304.8 tonnes. Compare this displacement with Discovery, 1,570 tons (1,600 tonnes)

- ^ a b The distance was 97 geographical miles (112 statute miles, 180 km); most accounts of the expedition give the "97 miles" distance without giving the equivalent in statute miles, the symbolism of "under 100 miles" being considered all-important.

- ^ Amundsen, Vol. II, p. 115

- ^ Shackleton had joined Scott and Edward Wilson on a march south, to establish a record southern latitude at 82°17′S. All three had suffered on the return journey from exhaustion and probable incipient scurvy, but Shackleton was the worst affected. See Preston, pp. 65–66

- ^ Preston, p. 68

- ^ Huntford, p. 117

- ^ Huntford, p. 120. "To prove himself a better man than Scott", according to Albert Armitage

- ^ Huntford, pp. 120–21. Terra Nova, later Scott's expedition ship, was one of two ships sent in 1903–04 to relieve the icebound Discovery.

- ^ Fisher, p. 99

- ^ Huntford, p. 145

- ^ a b c Fisher, pp. 102–03 Cite error: The named reference "Fisher_101–03" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Huntford, p. 156

- ^ a b Shackleton, pp. 2–3 Cite error: The named reference "Shackleton_2–3" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Ponies had, however, been used by Frederick Jackson during the Jackson-Harmsworth Arctic expedition of 1894–97. Despite Jackson's contradictory report of their prowess, as recorded by Huntford, pp. 171–72, and against specific advice from Nansen (Huntford, p. 171) Shackleton was impressed enough to take 15 ponies, later scaled down to 10.

- ^ a b Huntford, pp. 158–59 Cite error: The named reference "Huntford_158–59" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Bjorn was eventually acquired by German explorer Wilhelm Filchner and, renamed Deutschland, was used in his 1911–13 voyage to the Weddell Sea. Huntford, p. 339.

- ^ a b c d Shackleton, pp. 5–11 Cite error: The named reference "Shackleton_5–11" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Huntford, p. 175

- ^ a b Huntford, pp. 178–79 Cite error: The named reference "Huntford_178–79" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Otherwise Edward Guinness, head of the Anglo-Irish brewing family

- ^ Huntford, p. 183

- ^ Shackleton, p. 20

- ^ a b c d Riffenburgh, pp. 138–41 Cite error: The named reference "Riffenburgh_138–41" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Huntford, p. 314

- ^ It eventually required a British government grant of £20,000 to enable Shackleton to repay his guarantors, and it is likely that some debts were simply written off. Huntford, p. 315

- ^ Huntford, p. 312

- ^ An Antarctic post office had been established in the South Orkney Islands in 1904 at the Orcadas meteorological station set up by William Speirs Bruce's Scottish National Antarctic Expedition.

- ^ a b Riffenburgh, pp. 109–10

- ^ Of those who refused Shackleton, only Wilson actually went with Scott on the Terra Nova Expedition.

- ^ Most accounts tell the story of Shackleton spotting Joyce on top of a bus as it passed the expedition's London offices and sending someone out to find him and bring him in. Riffenburgh, pp. 125–26

- ^ Riffenburgh, p. 133

- ^ Riffenburgh, pp. 123–25

- ^ Shackleton, pp. 17–18

- ^ Apart from the two doctors it consisted of the 41-year-old biologist John Murray and the 21-year-old geologist Raymond Priestley, a future founder of the Scott Polar Research Institute. Riffenburgh, p. 134 and p. 303

- ^ David actually joined the expedition as a physicist and was also appointed chief scientific officer.

- ^ Fisher, p. 121

- ^ a b c d e f g h Riffenburgh, pp. 110–16 Cite error: The named reference "Riffenburgh_110–16" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ The exact distance of the tow is difficult to establish. The straight-line distance between Lyttelton and the Arctic circle is 1,376 nautical miles. Riffenburgh (p. 148) rounds this up to 1,400, which gives the statute mile approximation of 1,650. Shackleton (p. 38) gives the length of tow as 1,510 miles, without stipulating whether statute or nautical.

- ^ a b Riffenburgh, pp. 144–45 Cite error: The named reference "Riffenburgh_144–45" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Fisher, pp. 32–33

- ^ a b Riffenburgh, p. 152 Cite error: The named reference "Riffenburgh_151–53" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Shackleton named the bay after the large number of whales seen there.

- ^ Shackleton, pp. 52–53

- ^ Shackleton, p. 55

- ^ a b Riffenburgh, pp. 161–67 Cite error: The named reference "Riffenburgh_161–67" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Riffenburgh p. 170

- ^ a b c d e f Riffenburgh, pp. 171–76 Cite error: The named reference "Riffenburgh_171–77" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Shackleton, pp. 81–91

- ^ Riffenburgh, p. 185

- ^ Mills, p. 65

- ^ Of ten ponies shipped from New Zealand, one died during the sea voyage and another shortly after arrival.

- ^ Mills, p. 67

- ^ Huntford, pp. 237–38

- ^ Huntford, pp. 234–35

- ^ Riffenburgh, p. 201

- ^ Shackleton, p. 153

- ^ Shackleton, p. 171

- ^ Riffenburgh, p. 193

- ^ Mills, p. 80, quoting Frank Wild's diary

- ^ Shackleton, p. 180

- ^ Wild, diary, quoted by Mills, p. 93

- ^ a b Huntford, p. 263–64 Cite error: The named reference "Huntford_263–64" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Riffenburgh, p. 226

- ^ Shackleton, p. 200

- ^ Shackleton, p. 204

- ^ Shackleton, p. 205. The North reference was to Peary's then farthest north of 87°6′N.

- ^ Mills, p. 96

- ^ Shackleton, p. 207

- ^ Huntford, p. 270

- ^ Shackleton, p. 210

- ^ Three years later, on reaching the South Pole, Amundsen named the same plateau after King Haakon of Norway (Amundsen, Vol II p. 122). Neither name survives on modern maps.

- ^ a b c d e Riffenburgh, p. 251–61 Cite error: The named reference "Riffenburgh_251–61" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Wild diary, quoted in Mills, p. 108

- ^ Shackleton, p. 221

- ^ Shackleton, p. 223

- ^ Riffenburgh, p. 261

- ^ Riffenburgh, pp. 262–63

- ^ a b c Riffenburgh, pp. 274–78 Cite error: The named reference "Riffenburgh_274–78" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ The dry valley (snow-free) region of the western mountains had been discovered during Captain Scott's western journey in 1903, but had yet to be properly surveyed.

- ^ Huntford, p. 238

- ^ Shackleton, pp.260–62

- ^ Shackleton, p. 265

- ^ Riffenburgh, p. 238

- ^ Shackleton, pp. 291–92 (David's account). Mawson's amusing telling of the story is on Riffenburgh, p. 241.

- ^ a b c Riffenburgh, pp. 241–49 Cite error: The named reference "Riffenburgh_241–49" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Riffenburgh, pp. 269–73 Cite error: The named reference "Riffenburgh_269–73" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Riffenburgh, p. 279

- ^ Huntford, p. 308

- ^ Scott's reluctance was recorded by future Shackleton biographer Hugh Robert Mill, the RGS librarian: Riffenburgh, p. 286

- ^ See Crane, p. 432, for analysis of this decision by Scott.

- ^ Shackleton, p. 362

- ^ Shackleton, p. 210

- ^ Riffenburgh, p. 294

- ^ Huntford, p. 315

- ^ a b Riffenburgh, pp. 289–90 Cite error: The named reference "Riffenburgh_289–90" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Riffenburgh, p. 300

- ^ Mawson led the 1911–13 Australian Antarctic Expedition; Priestley was part of the Terra Nova Expedition's scientific team.

- ^ Riffenburgh, pp. 302–03

- ^ Riffenburgh, pp. 306–07

Sources

- Amundsen, Roald: The South Pole Vols I & II C Hurst & Co. Publishers, London 1976 ISBN 0 903983 47 8

- Crane, David: Scott of the Antarctic Harper Collins, London 2005 ISBN 0 00 715068 7

- Fisher, Margery and James: Shackleton James Barrie Books, London 1957

- Huntford, Roland: Shackleton Hodder & Stoughton, London 1985 ISBN 0 340 25007 0

- Mills, Lief: Frank Wild Caedmon of Whitby, Whitby 1999 ISBN 0 905355 48 2

- Preston, Diana: A First Rate Tragedy Constable, London 1999 ISBN 0 094795 30 4

- Riffenburgh, Beau: Nimrod Bloomsbury Publishing, London 2005 ISBN 0 7475 7253 4

- Shackleton, Ernest: The Heart of the Antarctic William Heinemann, London 1911

External links

- British Antarctic Expedition 1907–09 Antarctic Heritage Trust

- Crew list and biographies from Coolantarctica

- Nimrod Expedition 1907-09 Glasgow Digital Library

- Shackleton hut to be resurrected at the BBC