Nobles of the Robe

Under the Old Regime of France, the Nobles of the Robe or Nobles of the Gown (Template:Lang-fr) were French aristocrats whose rank came from holding certain judicial or administrative posts. As a rule, these positions did not of themselves give the holder a title of nobility, such as baron, count, or duke (although the holder might also hold such a title), but were almost always attached to a specific function. The offices were often hereditary, and by 1789 most Nobles of the Robe had inherited their positions. The most influential of them were the 1,100 members of the thirteen parlements, or courts of appeal. They were distinct from the "Nobles of the Sword" (Template:Lang-fr), whose nobility was based on their families' traditional function as the knightly class, and whose titles were usually attached to a particular feudal fiefdom, a landed estate held in return for military service. Together with the older nobility, the Nobles of the Robe made up the Second Estate in pre-revolutionary France.[1]

Origins

Because these nobles, especially the judges, had often studied at a university they were called Nobles of the Robe after the robes or gowns scholars wore, especially at commencement ceremonies. Originally given out as rewards for services to the king, the offices became venal, a commodity to be bought and sold (under certain conditions of aptitude). This practice became official with the edict of la Paulette, the Paulette being the tax paid by the holder to keep the office hereditary . As hereditary offices, they were often passed from father to son creating a class consciousness. Nobles of the Robe were often considered by Nobles of the Sword to be of inferior rank because their status was not derived from military service and/or land ownership. The elite Nobles of the Robe, such as the members of the parlements, fought to preserve their status alongside the Nobles of the Sword in pre-revolutionary society.

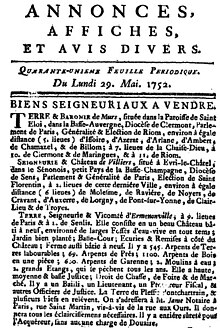

Originally, the offices within the Nobles of the Robe were relatively accessible due to their venal nature. In the 17th century, the office of councillor in the Parlement sold for 100,000 livres. By the mid-18th century, its value was reduced to half, due to the proliferation of offices.[2] However, after the 17th century the descendants of those who had earned the rank as a reward for services to the monarchy fought to limit access to the class. The Nobles of the Robe protested heavily when the monarchy, in desperate need of money, would create massive numbers of such positions within the bureaucracy to raise revenue. A common family strategy was to designate a second or third son to enter the church while the elder sons pursued a career in the robe or the military.[3] Access to nobility through a judiciary office hence became practically barred in the 18th century. But there existed other offices for sale: a secrétaire-conseiller du roi acquired first-degree nobility immediately, and hereditary nobility after 20 years.[4] The office was not cheap (120,000 livres in 1773), but it was a sinecure, with no preconditions and no obligations. Real nobility looked down on it as a savonette à vilain (the commoners' soap). In order to become a baron or vicomte the new untitled nobleman then still needs to acquire a fief - baronies, viscounties etc. were also sold as investment goods - and to add the name of the fief to his family name. E.g. Antoine Crozat, having become extremely wealthy, but a mere son of peasants, acquired the barony of Thiers in 1714 for the price of 200,000 livres. In some parts of France, the new baron or vicomte must be registered by the Estates (who could refuse, as did the Estates of Béarn for Vincent Laborde de Montpezat in 1703).

The Enlightenment and the French Revolution

Nobles of the Robe played key roles in the French Enlightenment. The most famous, Montesquieu, was one of the earliest Enlightenment figures. During the French Revolution, the Nobles of the Robe lost their place when the parlements and lower courts were abolished in 1790.

See also

Notes

- ^ Ford, 1953

- ^ Roland Mousnier, The Institutions of France Under the Absolute Monarchy, 1598-1789, Volume 2, p 346 .

- ^ Peter Campbell, Power and politics in old regime France, 1720-1745 (Routledge, 2003) p 22

- ^ the office of secrétaire-conseiller du roi is not to be confounded with that of conseiller du roi, a general denomination for a number of offices that did not confer nobility (though the ambiguity has been exploited by unscrupulous genealogists in attempts to prove ancient nobility for commoners seeking a "rétablissement de noblesse").

Further reading

- Ford, Franklin L. Robe and sword: the regrouping of the French aristocracy after Louis XIV (Harvard U.P. 1953)