Pacha (Inca mythology)

| Inca Empire |

|---|

|

| Inca society |

| Inca history |

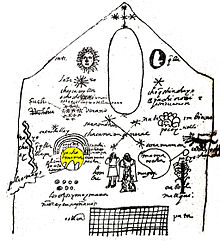

The pacha (often translated as world) was an Incan concept for dividing the different spheres of the cosmos in Incan mythology. There were three different levels of pacha: the hana pacha, hanan pacha or hanaq pacha (Quechua, meaning "world above"), ukhu pacha ("world below"), and kay pacha ("this world").[1]The realms are not solely spatial, but were simultaneously spatial and temporal.[2] Although the universe was considered a unified system within Incan cosmology, the division between the worlds was part of the dualism prominent in Incan beliefs. This dualism found that everything which existed had both features of any feature (both hot and cold, positive and negative, dark and light, etc.).[3]

Meaning of pacha

Pacha is often translated as "world" in Quechua, but the concept also includes a temporal context of meaning.[2] Catherine J. Allen writes that "The Quechua word pacha may refer to the whole cosmos or to a specific moment in time, with interpretation depending on the context."[4] Allen thus chooses to translate the term as "world-moment."[4] Pachas overlap and interact in Incan cosmology presenting both a material order and a moral order.[4] Dr. Atuq Eusebio Manga Qespi, native Quechua speaker, directly states that pacha should be translated to Spanish as tiempo-espacio (spacetime in English).[5]

Hanan pacha

The upper realm that included the sky, the sun, the moon, the stars, the planets, and constellations (of particular importance being the milky way) was called hanan pacha (in Quechua) or alaxpacha (in Aymara).[6][7] The hanan pacha was inhabited by both Inti, the masculine sun god, and Mama Killa, the feminine and moon goddess.[2] In addition, the Illapa, the god of thunder and lightning, also existed in the hanan pacha realm.[2] After Catholic missionary activity the hanan pacha was interpreted as akin to Heaven.[8]

Kay pacha

Kay pacha (in Quechua) or aka pacha (in Aymara)[6] is the perceptible world where people, animals, and plants all inhabit. Kay pacha is often impacted by the struggle between hanan pacha and ukhu pacha.[2]

Ukhu pacha

Ukhu pacha (alternatively urin pacha (in Quechua)), manqhapacha or manqhipacha (in Aymara)[6] is the inner world. Ukhu pacha is associated with the dead as well as with new life.[7] As the realm of new life, the realm is associated with harvesting and Pachamama, the fertility goddess.[9] As the realm associated with the dead, ukhu pacha is inhabited by the supay, a group of demons which torments the living.[9]

Human disruptions of the ukhu pacha were considered a sacred matter and ceremonies and rituals were often associated with disturbances of the surface. In Incan custom, during the time of tilling for potato crops the disturbance of the soil was met with a host of sacred rituals.[10] Similarly, rituals often brought food, drink (often alcoholic) and other comforts to cave openings for the spirits of ancestors.[9]

When the Spanish conquered the area, rituals about ukhu pacha became crucial in missionary activity and mining operations. Brown contends that the dualistic nature and rituals surrounding openings to ukhu pacha may have made it easier to initially get indigenous laborers to work in the mines.[11] However, at the same time, because mining was considered a perturbation of "subterranean life and the spirits that ruled it; they yielded to sacredness that did not belong to the familiar universe, a deeper and riskier sacredness."[11] In order to insure that the perturbation did not cause evil in the miners or the world, indigenous populations made traditional offering to the supay. However, Catholic missionaries preached that the supay were purely evil and equated them with the devil and hell and thus prohibited offerings.[11] Ritual surrounding ukhu pacha thus retained importance even after Spanish conquest.

Connections between pachas

Although the different worlds are distinct, there is a variety of connections between them. Caves and springs serve as connections between ukhu pacha and kay pacha. Rainbows and lightning serve as connections between hanan pacha and kay pacha.[7] In addition, human spirits after death could inhabit any of the levels. Some would remain in kay pacha until they had finished business, while others might move to the other levels.[8]

The most significant connection between the different levels was at Pachakutiq or a cataclysm. These were the instances when the different levels would all impact one another transforming the entire order of the world. These could come as a result of earthquakes or of other cataclysmic events.[2]

See also

References

- ^ "Diccionario: Quechua - Español - Quechua, Simi Taqe: Qheswa - Español - Qheswa" (PDF). Diccionario Quechua - Español - Quechua. Gobierno Regional del Cusco, Perú: Academía Mayor de la Lengua Quechua. 2005.

- ^ a b c d e f Heydt-Coca, Magda von der (1999). "When Worlds Collide: The Incorporation Of The Andean World Into The Emerging World-Economy In The Colonial Period". Dialectical Anthropology. 24 (1): 1–43.

- ^ Minelli, Laura Laurencich (2000). "The Archeological-Cultural Area of Peru". The Inca World: The Development of Pre-Columbian Peru, A.D. 1000–1534. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

- ^ a b c Allen, Catherine J. (1998). "When Utensils Revolt: Mind, Matter, and Modes of Being in the Pre-Columbian". RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics (33): 18–27.

- ^ Atuq Eusebio Manga Qespi, Instituto de lingüística y Cultura Amerindia de la Universidad de Valencia. Pacha: un concepto andino de espacio y tiempo. Revísta española de Antropología Americana, 24, p. 155–189. Edit. Complutense, Madrid. 1994

- ^ a b c Radio San Gabriel, "Instituto Radiofonico de Promoción Aymara" (IRPA) 1993, Republicado por Instituto de las Lenguas y Literaturas Andinas-Amazónicas (ILLLA-A) 2011, Transcripción del Vocabulario de la Lengua Aymara, P. Ludovico Bertonio 1612 (Spanish-Aymara-Aymara-Spanish dictionary)

- ^ a b c Strong, Mary (2012). Art, Nature, Religion in the Central Andes. Austin, Tx: University of Texas Press.

- ^ a b Gonzalez, Olga M. (2011). Unveiling Secrets of War in the Peruvian Andes. Chicago,Derp IL: University of Chicago Press.

- ^ a b c Steele, Richard James (2004). Handbook of Inca Mythology. ABC-CLIO.

- ^ Millones, Luis (2001). "The Inner Realm". The Potato Treasure of the Andes.

- ^ a b c Brown, Kendall W. (2012). A History of Mining in Latin America. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.