Perspective (geometry)

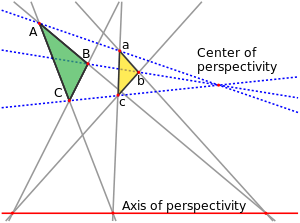

Two figures in a plane are perspective from a point O if the lines joining corresponding points of the figures all meet at O. Dually, the figures are said to be perspective from a line if the points of intersection of corresponding lines all lie on one line. The proper setting for this concept is in projective geometry where there will be no special cases due to parallel lines since all lines meet. Although stated here for figures in a plane, the concept is easily extended to higher dimensions.

Terminology

The line which goes through the points where the figure's corresponding sides intersect is known as the axis of perspectivity, perspective axis, homology axis, or archaically, perspectrix. The figures are said to be perspective from this axis. The point at which the lines joining the corresponding vertices of the perspective figures intersect is called the center of perspectivity, perspective center, homology center, pole, or archaically perspector. The figures are said to be perspective from this center.[1]

Perspectivity

If each of the perspective figures consists of all the points on a line (a range) then transformation of the points of one range to the other is called a central perspectivity. A dual transformation, taking all the lines through a point (a pencil) to another pencil by means of an axis of perspectivity is called an axial perspectivity.[2]

Triangles

An important special case occurs when the figures are triangles. Two triangles that are perspective from a point are called a central couple and two triangles that are perspective from a line are called an axial couple.[3]

Notation

Karl von Staudt introduced the notation to indicate that triangles ABC and abc are perspective.[4]

Related theorems and configurations

Desargues' theorem states that, a central couple of triangles is axial. The converse statement, an axial couple of triangles is central, is equivalent (either can be used to prove the other). Desargues' theorem can be proved in the real projective plane, and with suitable modifications for special cases, in the Euclidean plane. Projective planes in which this result can be proved are called Desarguesian planes.

There are ten points associated with these two kinds of perspective: six on the two triangles, three on the axis of perspectivity, and one at the center of perspectivity. Dually, there are also ten lines associated with two perspective triangles: three sides of the triangles, three lines through the center of perspectivity, and the axis of perspectivity. These ten points and ten lines form an instance of the Desargues configuration.

If two triangles are a central couple in at least two different ways (with two different associations of corresponding vertices, and two different centers of perspectivity) then they are perspective in three ways. This is one of the equivalent forms of Pappus's (hexagon) theorem.[5] When this happens, the nine associated points (six triangle vertices and three centers) and nine associated lines (three through each perspective center) form an instance of the Pappus configuration.

The Reye configuration is formed by four quadruply perspective tetrahedra in an analogous way to the Pappus configuration.

See also

Notes

- ^ Young 1930, p. 28

- ^ Young 1930, p. 29

- ^ Dembowski 1968, p. 26

- ^ H. S. M. Coxeter (1942) Non-Euclidean Geometry, University of Toronto Press, reissued 1998 by Mathematical Association of America, ISBN 0-88385-522-4 . 21,2.

- ^ Coxeter 1969, p. 233 exercise 2

References

- Coxeter, Harold Scott MacDonald (1969), Introduction to Geometry (2nd ed.), New York: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-471-50458-0, MR 0123930

- Dembowski, Peter (1968), Finite geometries, Ergebnisse der Mathematik und ihrer Grenzgebiete, Band 44, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 3-540-61786-8, MR 0233275

- Young, John Wesley (1930), Projective Geometry, The Carus Mathematical Monographs (#4), Mathematical Association of America