Philco computers

Philco was one of the pioneers of transistorized computers, also known as second generation computers. After the company developed the surface barrier transistor, which was much faster than previous point-contact types, it was awarded contracts for military and government computers. Commercialized derivatives of some of these designs became successful business and scientific computers. The TRANSAC (Transistor Automatic Computer) Model S-1000 was released as a scientific computer. The TRANSAC S-2000 mainframe computer system was first produced in 1958, and a family of compatible machines, with increasing performance, was released over the next several years.

However, the mainframe computer market was dominated by IBM. Other companies could not deploy resources for development, customer support and marketing on the scale that IBM could afford, making competition in this segment difficult after the introduction of the IBM 360 family. Philco went bankrupt and was purchased in 1961 by Ford Motor Company, but the computer division carried on until the Philco division of Ford exited the computer business in 1963. The Ford company maintained one Philco mainframe in use until 1981.

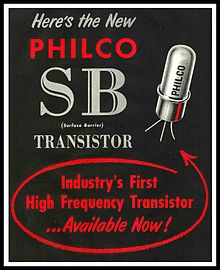

The surface-barrier transistor

[edit]The surface-barrier transistor developed by Philco in 1953 had a much higher frequency response than the original point-contact transistors. The transistor was made of a thin crystal of germanium, which was electrolytically etched with pits on either side forming a very thin base region, on the order of 5 micrometers. Philco's process for etching was United States patent number 2,885,571. Philco surface-barrier transistors were used in TX-0, and in early models of what would become the DEC PDP product line. Although relatively fast, the small size of the devices limited their power to circuits operating at a few tens of milliwatts.

Military and government

[edit]Between 1955 and 1957, Philco built transistor computers for use in aircraft, models C-1000, C-1100, and C-1102, intended for airborne real-time applications. By 1957, the C-1102 had been used by a civilian sector customer.[1] The BASICPAC[2] AN/TYK 6V (first delivery in 1961),[3] COMPAC AN/TYK 4V (not completed),[4][5][6] and LOGICPAC[7] systems were built for the US Army as transportable computer systems for use with their Fieldata concept of integrated information management.

BASICPAC was a transistorized computer with up to 28,672 words of 38-bit core memory (including sign and parity), available in several configurations from a minimum system, to a truck-borne mobile version, to a fully expanded system. Basic clock periods was 1 microsecond (which gives a clock rate of 1 MHz),[8][9] with 12 microsecond memory access and a fixed-point multiplication taking 242 microseconds. Input/output was by paper tape reader and punch, or through a teletypewriter. With additional hardware, magnetic tape storage was also available, with up to seven I/O devices. The instruction set had 31 basic operation codes and nine opcodes for I/O [10]

CXPQ

[edit]Philco was contracted by the US Navy to build the CXPQ computer. One model was completed and installed at the David Taylor Model Basin. This design was later adapted to become the commercial TRANSAC S-2000.[11] Only one CXPQ was built.[12]

The CXPQ is a 48-bit transistorized computer.[13]

SOLO

[edit]In 1955, the National Security Agency through the US Navy contracted with Philco to produce a computer suitable for use as a workstation, with an architecture based on the vacuum-tube computer system called Atlas II already in use at the NSA, and similar to the commercial UNIVAC 1103. At the time, Philco was the largest producer of surface barrier transistors, which were the only type available with the speed and quantities required for a computer. The SOLO prototype was delivered in 1958, but required extensive debugging at NSA. Difficulties were encountered with core memory and power supplies. SOLO used paper tape and teleprinter machines for input and output.[14] SOLO cost about $1 million US, and contained 8,000 transistors. While the system was extensively used for training, testing, research and development, no additional units were ordered. SOLO was removed from active service in 1963.[15] The design of the SOLO became commercialized as Philco's TRANSAC Model S-1000.

Commercial

[edit]S-1000

[edit]The TRANSAC S-1000 was a scientific computer with a 36-bit word length and 4096 words of core memory. It was packaged in a container about the size of a large office desk, and used only 1.2 kilowatts, much less than vacuum-tube-based computers of similar capacity.[16] In a 1961 survey, about 15 S-1000 computer installations had been identified.[12]

It weighed about 1,650 pounds (750 kg).[17]

S-2000

[edit]

The TRANSAC S-2000 was a large mainframe system intended for both business and scientific work. It had a 48-bit word length and supported calculations in fixed point, floating point and binary-coded decimal formats. The original S-2000 "TRANSAC" (Transistor Automatic Computer) released in 1958[18] was later designated Model 210; it was used internally at Philco. Similar to the Control Data Corporation Model 1604, it was a 48-bit fully transistorized computer. Three succeeding models were released in the series, all compatible with the software of the original model. The Model 211 was introduced in 1960, using micro-alloy diffused field-effect transistors, requiring significant redesign of circuits compared to the original.

The TRANSAC S-2000/Philco 210/211 weighed about 2,000 pounds (910 kg).[19]

By 1964, eighteen Model 210, eighteen Model 211 and seven Model 212 systems had been sold.[12]

After Philco was purchased by Ford Motor Company, the Model 212 was introduced in 1962[20] and released in 1963. It had 65,535 words of 48-bit memory. Initially made with 6-microsecond core memory, it had better performance than the IBM 7094 transistor computer. It was later upgraded in 1964 to 2-microsecond core memory, which gave the machine floating-point performance greater than the IBM 7030 Stretch computer. A Model 213 was announced in 1964 but never built. By that time competition from IBM had made the Philco computer operations no longer profitable for Ford, and the division was closed down.[21]

The Model 212 could carry out a floating-point multiplication in 22 microseconds. Each word contained two 24-bit instructions with 16 bits of address information and eight bits for the opcode. There were 225 different valid opcodes in the Model 212; invalid opcodes were detected and halted the machine. The CPU had an accumulator register of 48 bits, three general-purpose registers of 24 bits, and 32 index registers of 15 bits. Main memory size ranged from 4K words to 64K words. Only the first model had a magnetic drum memory; later editions used tape drives.

The Model 212 weighed about 6,500 pounds (3.3 short tons; 2.9 t).[22]

Software for the S-2000 initially consisted of TAC (Translator-Assember-Compiler), and ALTAC, a FORTRAN II-like language with some differences from the IBM 704 FORTRAN implementation. A COBOL compiler was also available, targeted at business applications.

The Philco 2400 was the input/output system for the S-2000. Operations such as reading cards or printing were carried out through magnetic tapes, thereby offloading the S-2000 from relatively slow input/output processing.[23] The 2400 had a 24-bit word length and could be supplied with 4K to 32K characters (1K to 8K words) of core memory, rated at 3-microsecond cycle time. The instruction set was aimed at character I/O use.

The idea of base registers, implemented in Philco computers, influenced the design of IBM/360.[24]

The last Philco TRANSAC S-2000 Model 212 was taken out of service in December 1981, after 19 years service at Ford.[25]

References

[edit]- ^ Historical Narrative Statement of Richard B. Mancke, Franklin M. Fisher and James W. McKie, Exhibit 14971, US vs. IBM, Part 1. July 1980. pp. 238–240.

- ^ "1960s computer ads created by the real Mad Men". Pingdom Royal. A computer on a truck. 30 May 2013. BASICPAC ad from 1960, from Computers and Automation, December 1960

- ^ "MILITARY NOTES - 'Basicpac' Computer Systems". Military Review. 41 (2): 98. 1961. hdl:2027/uiug.30112106755934.

- ^ "Data processing equipment". Signals. 14 (7): 60. 1960. hdl:2027/mdp.39015013429793.

- ^ Weik, Martin H. (1961). A third survey of domestic electronic digital computing systems. Ballistic Research Laboratories.Report no. 1115. BASICPAC pp. 52-53. Aberdeen Proving Ground, Md. pp. 50–53. hdl:2027/mdp.39015023453221.

- ^ Missiles and Rockets. American Aviation Publications. 1967. p. 37.

- ^ Quadrennial report of the Chief Signal Officer, U. S. Army. [Washington?]. 1959. pp. 20–21. hdl:2027/mdp.39015022453172.

- ^ Berger, Arnold S. (2005). Hardware and Computer Organization: The Software Perspective. Newnes. pp. 66–67. ISBN 9780750678865.

- ^ "Clock Signals, Cycle Time and Frequency". www.pcguide.com. Retrieved 2018-03-14.

- ^ "BASICPAC Programming Manual" (PDF). Philco. January 1961. section 1.

- ^ Kenneth Flamm, Creating the Computer: Government, Industry and High Technology, Brookings Institution Press, 2010, ISBN 0815707215, page 122

- ^ a b c Martin H. Weik (January 1964). "Chapter III Tables of Computer Characteristics". A Fourth Survey Of Domestic Electronic Digital Computing Systems. Retrieved August 27, 2018.

- ^ "Philco Transistorized Automatic Computer CXPQ".

- ^ David L. Boslaugh, When Computers Went to Sea: The Digitization of the United States Navy, John Wiley & Sons, 2003, ISBN 0471472204, pp. 112-113

- ^ "History of NSA General-Purpose Electronic Digital Computers" (PDF). 1964. pp. 29–31.

- ^ J. L. Maddox; J. B. O'Toole; S. Y. Wong (1956). The TRANSAC S-1000 Computer. Eastern Joint Computer Conference. doi:10.1145/1455533.1455538. Retrieved August 27, 2018.

- ^ Weik 1964, PHILCO 1000.

- ^ United States. (1959). "COMPUTERS AND DATA PROCESSORS, NORTH AMERICA - Philco Corp., Transac S-2000, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 4". Digital Computer Newsletter. 11 (2): 4. hdl:2027/nyp.33433108192331.

- ^ Weik, Martin H. (Jan 1964). "PHILCO 210 & 211". ed-thelen.org. A Fourth Survey of Domestic Electronic Digital Computing Systems.

- ^ "Philco Corporation | Selling the Computer Revolution | Computer History Museum". www.computerhistory.org. Retrieved 2018-03-15.

- ^ Reilly, Edwin D. (2003). Milestones in Computer Science and Information Technology. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 201. ISBN 9781573565219.

philco model 212.

- ^ Weik 1964, PHILCO 212.

- ^ Stephen H. Kaisler, Birthing the Computer: From Drums to Cores, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2017, ISBN 144389625X, pages 232-237

- ^ Shustek, L. (2015), An interview with Fred Brooks, Association for Computing Machinery (ACM)

- ^ "Retirement video for the Philco 212 Mainframe Computer". Computer History Museum. Retrieved 26 November 2018.