Pike square

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2009) |

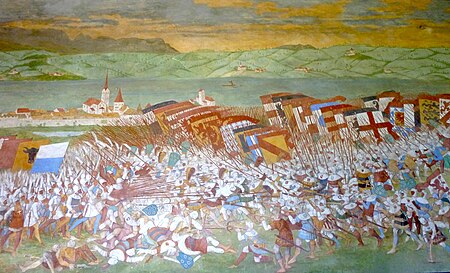

The pike square (Template:Lang-de, meaning crowd of force) was a military tactic developed by the Swiss Confederacy during the 15th century for use by its infantry.

History

The pike square was used to devastating effect at the Battle of Nancy against Charles the Bold of Burgundy in 1477, when the Swiss defeated a smaller but more powerful armored cavalry force. The battle is generally seen as one of the turning points that established the infantry as the primary fighting arm in European warfare from the 16th century onwards.

The Burgundian Compagnie d'ordonnance was a formidable combined arms force relying on close cooperation between heavily armored knights, dismounted men-at-arms, a variety of ranged troops including archers and crossbowmen, and an early form of field artillery. It was one of the most feared and most effective ground forces in 15th-century Europe, fresh from its victory over the French in the dynastic conflicts that followed the end of the Hundred Years' War. In response to the Burgundian threat the Swiss developed a tactic that could be used by mobile, lightly armored soldiers carrying only a long, steel-tipped pole for defence. However, the tactic depended on well trained and drilled troops who could move in unison while in close formation. While the use of pointed sticks to fend off cavalry was common throughout the Middle Ages, such barricades were usually fixed in position. The Swiss pikemen were to bring a change of paradigm by reintroducing the offensive element into pike warfare.

A pike square generally consisted of about 100 men in a 10×10 formation. While on the move, the pike would be carried vertically. However, the troops were drilled to be able to point their pikes in any direction while stationary, with the men in the front of the formation kneeling to allow the men in the center or back to point their pikes over their heads. While stationary, the staff of each pike could be butted against the ground, giving it resistance against attack. Squares could be joined together to form a battle line. If surrounded, pikes could still be pointed in all directions. A well drilled square could change direction very quickly, making it difficult to outmaneuver on horseback.

Charles did not believe that a force even twice his size on foot without archers could possibly pose him any threat. However, Charles and his forces found the pike square impossible to penetrate on horseback and dangerous to approach on foot. When threatened the square could point all of the pikes at the enemy forces and merely move inexorably toward its target. All these considerations aside, the primary strength of the Swiss pike formation lay in its famous charge, a headlong rush against the enemy with leveled pikes and a coordinated battle cry. At Nancy, the Swiss routed the Burgundians, and Charles himself died in the battle. This success was repeated on various European battlefields, most remarkably in the early battles of the Italian Wars. With their famed discipline and in combination with heavy cavalry like the gendarme, the Swiss pike squares were almost invincible on the late medieval battlefield. The dominance of the pure pike formation only came to an end when the pike and shot formation was introduced at the end of the fifteenth century.

The pike square dominated European battlefields and influenced the development of tactics well into the 17th century. Even when muskets became common, their slow rate of fire meant that soldiers armed with them were vulnerable to cavalry; to combat this, some soldiers continued to carry pikes until the improving performance of firearms and the introduction of the bayonet allowed armies to drop the use of pikes. "As Michael Roberts has demonstrated, major changes occurred between 1560 and 1660 in four areas: tactics, strategy, size of armies, and sociopolitical institutions…. At the tactical level, Maurice of Nassau's doctrinal innovations changed the traditional 50-foot-deep (15 m) pike square into a line of musketry only 10 feet deep, all of which minimized the effect of incoming fire while maximizing the outgoing fire effect."[1]

See also

Comparable formations

References

- ^ David Jablonsky (Professor of National Security Affairs U.S. Army War College) The Owl of Minerva flies at twilight: Doctrinal change and continuity and the revolution in military affairs (PDF) (see also Owl of Minerva)