Plesiadapis

| Plesiadapis Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| P. cooki fossil | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Superfamily: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | †Plesiadapis Gervais, 1877

|

| Type species | |

| †Plesiadapis tricuspidens | |

| Paleospecies[2][3] | |

|

†Plesiadapis walbeckensis Russell, 1964 | |

Plesiadapis is one of the oldest known primate-like mammal genera which existed about 55-58 million years ago in North America and Europe.[2] Plesiadapis means "near-Adapis", which is a reference to the Eocene lemuriform, Adapis. Plesiadapis tricuspidens, the type specimen, is named after the three cusps present on its upper incisors.

Origins and discovery

The first discovery of Plesiadapis was made by François Louis Paul Gervaise in 1877, who first discovered Plesiadapis tricuspidens in France. The type specimen is MNHN Crl-16, and is a left mandibular fragment dated to the early Eocene epoch.

This genus probably arose in North America and colonized Europe on a landbridge via Greenland. Thanks to the abundance of the genus and to its rapid evolution, species of Plesiadapis play an important role in the zonation of Late Paleocene continental sediments and in the correlation of faunas on both sides of the Atlantic. Two remarkable skeletons of Plesiadapis, one of them nearly complete, have been found in lake deposits at Menat, France.[2] Although the preservation of the hard parts is poor, these skeletons still show remains of skin and hair as a carbonaceous film—something unique among Paleocene mammals. Details of the bones are better preserved in fossils from Cernay, also in France, where Plesiadapis is one of the most common mammals.

Anatomy and remains

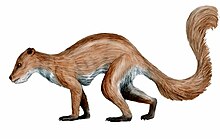

Nearly all of what is known about the anatomy of plesiadapiforms comes from fragmentary jaws and teeth, so most definitions of plesiadapiform genera and species are based on dentition. Plesiadapis' dentition shows a functional shift toward grinding and crushing in the cheek teeth as an adaptation towards increasing omnivority and herbivority. The dental formula for Plesiadapis is 2.1.3.32.1.3.3[4] The skull of Plesiadapis is relatively broad and flat, with a long snout with rodentlike jaws and teeth and long, gnawing incisors separated by a gap from its molars. Orbits are still directed to the side, unlike the forward-facing eyeballs of modern primates that enable three-dimensional vision.[5] Although its braincase was small by today's standards, it was larger than in the contemporary hoofed mammals, for instance. Plesiadapis had mobile limbs that terminated in strongly curved claws, and it sported a long bushy tail which is beautifully preserved in the Menat skeletons. The way of life of Plesiadapis has been much debated in the past. Climbing habits could be expected in a relative of the primates, but tree-dwelling animals are rarely found in such high numbers. Based on this and other evidence, some paleontologists have concluded that these animals were mainly living on the ground, like today's marmots and ground squirrels.[2] However, more recent investigations have confirmed that the skeleton of Plesiadapis is that of an adept climber, which can be best compared to tree squirrels or to tree-dwelling marsupials such as possums.[5] The short, robust limbs, the long, laterally compressed claws, and the long, bushy tail indicate that it was an arboreal quadruped. Remains found showed that it had a body mass of around 2.1 kilograms.[6]

Relationships and lineage

The following are possible shared derived features of Plesiadapiformes: maxillary-frontal contact in orbit, the presence of a suboptic foramen, an ossified external auditory meatus, the absence of a promontory artery, the absence of a stapedial artery, and a strong mastoid tubercle.[7]

Although the placement of the Plesiadapis lineage is still up for debate, the current consensus is that they are closest to early tarsier-like primates.[8] Plesiadapiformes have also been proposed as a nonprimate sister group to Eocene-Recent primates. A study done in 1987 linked Plesiadapiformes with adapids and omomyids through nine shared-derived features, six of which are cranial or dental: (1) auditory bulla inflated and formed by the petrosal bone, (2) ectotympanic expanded laterally and fused medially to the wall of the bulla, (3) promontorium centrally positioned in the bulla, and large hypotympanic sinus widely separating promontorium from the basisphenoid, (4) internal carotid entering the bulla posteriolaterally and enclosed in a bony tube, (5) nannopithex fold on the upper molars, and (6) loss of one pair of incisors.[7]

In 2013, a phylogenetic analysis that includes also the basal primate Archicebus positions Plesiadapis firmly outside of the Primates, as a sister group to both Primates and Dermoptera.[9]

References

- ^ McKenna, M. C, and S. K. Bell (1997). Classification of Mammals Above the Species Level. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-11012-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Gingerich, P.D. (1976). "Cranial anatomy and evolution of early Tertiary Plesiadapidae (Mammalia, Primates)". University of Michigan Papers on Paleontology. 15: 1–141.

- ^ Rose, K.D. (1981). "The Clarkforkian Land-Mammal Age and mammalian faunal composition across the Paleocene-Eocene boundary". University of Michigan Papers on Paleontology. 26: 1–197.

- ^ Fleagle, K. D. (1987). "The First Radiation—Plesiadapiform Primates". In Ciochon, R. L.; Fleagle, J. G. (eds.). Primate Evolution and Human Origins. Hawthorne: Aldine de Gruyter. pp. 41–51. ISBN 0-202-01175-5.

- ^ a b Szalay, F. S. & Delson, E. (1979). Evolutionary history of the Primates. Academic Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fleagle, J. G. (1988). Primate Adaptation and Evolution. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-260340-0.

- ^ a b Kay, Richard F.; Thewissen, J. G.; Yoder, Anne D. (1992). "Cranial anatomy of Ignacius graybullianus and the affinities of the Plesiadapiformes". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 89 (4): 477–498. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330890409.

- ^ Gingerich, P. D. (1975). New North American Plesiadapidae (mammalia, primates) and a biostratigraphic zonation of the Middle and Upper Paleocene. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Museum of Paleontology.

- ^ Ni, X.; Gebo, D. L.; Dagosto, M.; Meng, J.; Tafforeau, P.; Flynn, J. J.; Beard, K. C. (2013). "The oldest known primate skeleton and early haplorhine evolution". Nature. 498 (7452): 60–64. doi:10.1038/nature12200. PMID 23739424.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)