Porta Esquilina

The Porta Esquilina was a gate in the Servian Wall [1] Tradition dates it back to the 6th century BC, when the Servian Wall was said to have been built by the Roman king Servius Tullius, however modern scholarship and evidence from archaeology indicates a date in the fourth century BC.[2] The Porta Esquilina is also known as the Esquiline Gate.

Location

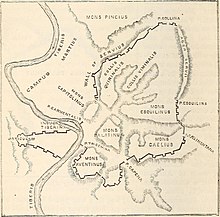

The Porta Esquilina allowed passage between Rome and the Esquiline hill, at the city’s east. The Esquiline hill served as Rome’s graveyard during the Republic and later as an area for some the emperor’s most beautiful gardens such as the Gardens of Maecenas.[3] Connecting northward to the Esquiline Gate was the agger, the heavily fortified section of the Servian Wall.[4] Just southwest of the Esquiline Gate were notable locations such as Nero’s Golden House, the Baths of Titus, and Trajan’s Baths.[5] Two major roads, the via Labicana and the via Praenestina, originate at the Porta Esquilina[6] but lead out of Rome as a single road until they separate near Rome's outer, Aurelian wall.[1]

History

Following from the concept of the pomerium, there seems to be an unofficial Roman “tradition” that certain killings were to be done “outside” of the city and thus several ancient authors include the Esquiline gate in their descriptions of such deeds. For example, in Cic. Pro. Clu. 37 the murder of Asinus of Larinum was done outside the Esquiline gate,[7] and in Tac. Ann. ii. 32, the astrologer Publius Marcius was executed by consuls outside the Esquiline gate.[8]

The Esquiline gate is also mentioned in ancient literature as an important way of entering and exiting Rome. Livy writes about the consul Valarius’s strategic plan to lure out Etruscan pillagers that had been preying on Roman fields. Valarius ordered cattle, which had been previously brought to safety within the city walls, to be sent outside through the Esquiline Gate so that when the Etruscans came down south to seize the cattle, the Romans could ambush the Etruscans from all sides.[9] Cicero, in a speech deemphasizing the greatness of triumph processions, mentions how he trampled his own Macedonian laurels underfoot while entering Rome through the Esquiline gate and this suggests that the Esquiline gate was used for triumph processions.[10] Another example of the Esquiline gate in ancient literature comes from Plutarch’s description of Sulla’s first march on Rome.[11] Sulla ordered the Esquiline gate secured and sent some of his forces to go through it. However, bricks and stones were hurled upon them by citizens that Marius had recruited to defend the city.[12]

Initially, the site of the Porta Esquilina was marked by a single arch that was built in the 1st Century AD, but it later became a triple arch structure in the 3rd Century AD [13] that had a peak height of 8.8m.[1] The conversion to a triple arch was sponsored by the equite M. Aurelius Victor in 262 AD to honor the Roman emperor Gallienus[14] Although archaeological evidence shows signs of extra pillar foundations, Aurelius Victor’s additional arches did not survive and today only the original, single arch remains.[13]

References

- ^ a b c Platner, S.B. and Ashby, T. A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. London: Humphrey Milford Oxford University, Press. 1929

- ^ Holloway, R. Ross. The Archaeology of Early Rome and Latium. London and New York: Routledge Press. 1994

- ^ Speake, Graham. A Dictionary of ancient history. Oxford, OX, UK: Blackwell Reference, 1994.

- ^ Palmer, Robert E. A. Jupiter Blaze, Gods of the Hills, and the Roman Topography of CIL VI 377. American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 80, No. 1, pp. 43-56. (Winter, 1976)

- ^ Bunson, Matthew. Encyclopedia of the Roman Empire. New York: Facts on File, 1994.

- ^ The Geography of Strabo. Literally translated, with notes, in three volumes. London. George Bell & Sons. 1903. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.01.0239

- ^ Cic. Pro. Clu. 37. M. Tullius Cicero. The Orations of Marcus Tullius Cicero, literally translated by C.D. Yonge, B. A. London. Henry G. Bogn, York Street, Covent Garden. 1856. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0019

- ^ Tac. Ann. ii. 32. Complete Works of Tacitus. Tacitus. Alfred John Church. William Jackson Brodribb. Sara Bryant. edited for Perseus. New York: Random House, Inc. Random House, Inc. reprinted 1942. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0078

- ^ Livy. ii. 11. 5 Livy. History of Rome. English Translation by. Rev. Canon Roberts. New York, New York. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.02.0026

- ^ Cic. In Pis. 61 M. Tullius Cicero. The Orations of Marcus Tullius Cicero, literally translated by C. D. Yonge, B. A. London. George Bell & Sons, York Street, Covent Garden. 1891. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0020

- ^ Plut. Sulla 9. 6

- ^ Carney, T. F.The Flight and Exile of Marius. Greece & Rome, 2nd Ser., Vol. 8, No. 2, pp. 98-121 (Oct., 1961). JSTOR 641640

- ^ a b Holland, Leicester B. The Triple Arch of Augustus. American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 50, No. 1, pp. 52-59 (Jan. - Mar., 1946).

- ^ Marindin, G. E., William Smith LLD,and William Wayte. A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities. Albemarle Street, London. John Murray. 1890. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0063