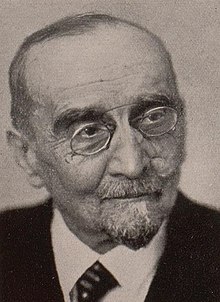

Rudolf Huch

Rudolf Huch | |

|---|---|

<1930, Magnus Merck | |

| Born | 28 February 1862 |

| Died | 13 January 1943 (aged 80) |

| Occupation(s) | Lawyer Author Essayist Satirist |

| Political party | NSDAP |

| Spouse | Margarete Hähn (1871–1963) |

| Children | 3s, 2d |

| Parents |

|

Rudolf Huch (28 February 1862 – 13 January 1943) was a Brazilian- born German jurist, essayist and author, primarily of satirical novels and short stories. He also produced a number of educational novels. A theme to which he returned repeatedly in his writing was upward social mobility from the ranks of the provincial petty bourgeoisie.[1] He is sometimes identified in sources by his pseudonym as "A. Schuster".[2][3][4]

Life[edit]

Provenance and early years[edit]

Rudolf Huch was born in Porto Alegre, but spent most of his childhood and indeed of his adult life in and around the Braunschweig region of Germany. At the time of his birth his father, Richard Huch (1830–1887) was running a wholesale importing business in Brazil which he had acquired following the death of an older brother. However, when Rudolf was approximately eighteen months old the family returned to Germany, and it was here, in Braunschweig, that the child grew up and attended school, while his father pursued his business career, trading in "colonial goods" from, in particular, Brazil.[1] The younger sister of Rudolf Huch, the author-historian Ricarda Octavia Huch, by whose career his own was always, to some extent, overshadowed, was born in Braunschweig in 1864.[5]

The boy was enrolled at the prestigious Martino-Katharineum (secondary school) in the early summer of 1871. As teenagers, at the recommendation of the family doctor, Rudolf and Ricarda Huch took lengthy annual holidays at the spa resort of Bad Suderode in the hill country between Braunschweig and Leipzig. From his later writing it is clear that Rudolf Huch would always look back on those childhood vacations in the Harz "paradise" with particular affection.[1] On leaving school he studied jurisprudence at the universities of Heidelberg and Göttingen, passing Parts I and II of his state law exams respectively in 1883 and 1887.[1][2] At Göttingen he joined the Corps Brunsviga (student fraternity).[6]

Lawyer[edit]

Huch remained in Braunschweig for some months, employed as a "Gerichtsassessor" (loosely, "trainee judge"), but the bankruptcy of his father's business ruled out any immediate possibility of a career in the government justice service.[1] He then relocated in 1888 to nearby Wolfenbüttel, where he lived until 1897, working as a lawyer and notary.[2] In 1897 he moved again, settling in Bad Harzburg. Here he would live for the rest of his life, apart from a five-year hiatus between 1915 and 1920, during which he made his home in Helmstedt.[7]

Writer[edit]

During the 1890s Huch seems to have found work as a small town lawyer less than fulfilling, and he embarked on a parallel career as a writer. His work betrays an underlying pessimism and melancholy, possibly driven by a belief that as a writer he would always be overshadowed by more confident relatives who would leave their own larger footprints on literary history. His first published work involved literary criticism. He found wider prominence with his aphoristic volume "Mehr Goethe" ("More Goethe"), published in 1899, which he described as "a high spirited cavalry charge against the diverse literary nonsenses of modern life".[a] in which he employed his satirical wit to uncover the contradictions in the book business, and to ridicule the fashionable superman archetypes of the time and the accompanying Nietzsche cult. He also railed against the nineteenth century revival of Naturalism and took delight in deriding its manifestations on the theatre stage.[2]

As a writer of fiction Huch came to be seen as a writer of stories in the tradition of Goethe and, more recently, of Keller and Raabe. He himself was particularly conscious of his self-appointed role as an heir to Wilhelm Raabe, describing himself on at least one occasion as a "Romantiker von Geblüt" ("romantic by blood").[8][9] His mostly satirical narratives, critical of contemporary society, including a number of autobiographical pieces, found a wide readership during the first part of the twentieth century.[7]

His first novel, "Tagbuch eines Höhlenmolchs" (literally "Dairy of a Giant Salamander") was probably written during 1894. It was published under the pseudonym "A. Schuster" in 1896, and reprinted in 1900, this time under the author's real name.[10] The book is a brutal satirical assault against the social customs he had observed among the townsfolk of Braunschweig and Wolfenbüttel.[11] During this first phase of his creativity Huch also wrote a number of stage plays. Most of these were comedies. An early exception was "Menschenfreund" ("Philanthropist"), a stage tragedy published in 1895.[12]

Of the thirty or so mostly satirical novels that Rudolf Huch produced two, in particular, stand out for the way in which they retained the support of critics and readers, even after the author's death. These were both, in their ways, sociological studies, "Die Beiden Ritterhelm" ("Both the Knights' Helmets") and "Die Familie Hellmann" ("The Hellmann Family"), published in 1908/09 and 1909.[3] The second of these was reprinted more than twenty times. It differs from earlier works in the extent to which the author moves beyond simple caricatures and stereotypes, demonstrating a hitherto undisclosed skill in respect of careful character development and an understanding of the positive nature of "true humanity" with all its overlapping elements.[2] Also worth picking out for special mention is the 1911 picaresque novel, "Wilhelm Brinkmeyers Abenteuer, von ihm selbst erzählt" ("Wilhelm Brinkmeyer's Adventure, as related by himself"), structured as a series of adjusted memories cloaked in the hypocritical gestures of an honest man, which even today merits high praise as a timeless gem. The book's appeal and humour are driven by a tension between the reader's perception of reality and the way in which that reality is presented.[2]

Among his more noteworthy short stories is "Der tolle Halberstädter" (loosely, "The Superman of Halbertadt": 1910) which bases its central figure of "Super Christian" on the military commander Christian the Younger of Brunswick (1599–1626), a previously little remembered younger son of Henry Julius, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg (1564–1613). Also worthy of mention and particularly popular with readers were his "Lied der Parzen" ("Song of the Parzen": 1920), drawing inspiration from Iphigenia in Tauris by Euripides (and, subsequently, by Goethe) and the Bad Honnef story "Spiel am Ufer" (loosely, "Game on the River Bank": 1927).

In addition to his books, Huch remained active as a culture and arts critic and as an essayist. Like his sister, he continued to contribute articles of literary scholarship. In particular, Aphorism was a device with which he was identified. Sympathetic commentators insist that despite the occasional savagery of his social and cultural criticism, there was always an underlying positivity shaped by the author's inherent humanism. "Sincerity, boldness, love and spirituality" were all core elements in Huch's version of the true human condition ("... wahres Menschentum").[2]

In 1925 Huch also produced a new edition of Rudolf von Jhering's respected 1872 work "Der Kampf ums Recht" (loosely, "The Fight over Law and Justice") for the Leipzig-based Reclam-Verlag publishing house.[13]

The final decade of Rudolf Huch's life, between 1933 and 1943, was lived under National Socialism. It has done nothing for Huch's posthumous reputation that after they came to power the National Socialists exploited the social criticism of the petty bourgeoisie the ooze from the pages of his novels to denigrate their political adversaries and infer endorsement of their state-mandated antisemitism. It is, however, hard to see Huch's books as inherently antisemitic, given the popularity they enjoyed within the German-Jewish community during the years of the republic. As political polarisation spilled onto the streets and the Reichstag became deadlocked, Huch was nevertheless one of those who moved towards Hitlerism. In 1933 he was accepted into the Prussian Academy of Arts (Poetry section) shortly after 40 members considered politically undesirable had been resigned from the institution.[12] Those excluded in 1933 included his sister, who had been an academician since 1926.[14] In October 1933 Huch's was one of 87 signatures on the infamous proclamation of loyalty to Adolf Hitler from German writers, which appeared in the Vossische Zeitung. A number of those who signed, when later they were moved to understand in greater depth the sheer inhumanity of Hitler's vision for Germany, recanted with varying levels of openness and conviction. Rudolf Huch (who was 71 when the declaration was published) did not.[15] In 1934 he published the 76 page propaganda booklet "Israel und wir".[16] Although there is no record of further public endorsement of the government on this level by Huch, his novels continued to be popular with readers through the twelve Hitler years. After he died at the start of 1943 work began on a tribute publication to be entitled "im Einvernehmen mit dem Dichter". Nevertheless, despite the abundance of his own published output, it never reached before two volumes, and after the war ended two years later work on it ceased. With the western two thirds of Germany divided and under military occupation after 1945, three of Huch's later works, published during the twelve Hitler years, were placed on the "Liste der auszusondernden Literatur" (loosely, "List of Literature to be weeded out") in the Soviet occupation zone.[17][18]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Bernd Sternal (6 February 2019). Rudolf Huch (1862 - 1943). Books on Demand. pp. 118–121. ISBN 978-3-7481-9604-4.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h Eckhard Schulz (1972). "Huch, Rudolf (Pseudonym A. Schuster)". Neue Deutsche Biographie. Historische Kommission bei der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (HiKo), München. p. 708. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ a b "Rudolf H., den föregåendes broder ..." Nordisk familjebok. Project Runeberg. p. 481. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ Bodo Pieroth (21 August 2018). Rudolf Huch. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. pp. 146–149. ISBN 978-3-11-061733-7.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Dr. Peter Czoik. "Ricarda Huch". Autorinnen & Autoren. Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, München. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ Georg Nilreh (22 August 2012). Footnote 46. epubli. p. 14. ISBN 978-3-8442-3066-6.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Kurt Hoffmeister (13 April 2017). Rudolf Huch, ein bissiger Kritiker kleinstädtischer Heuchelei. Books on Demand. pp. 181–182. ISBN 978-3-7431-3045-6.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Ewald Lüpke (21 November 2013). Gruss ān Rudolf Huch. Springer-Verlag. p. 41. ISBN 978-3-663-02556-6.

- ^ "Rudolf Huch (1862–1943), Schriftsteller. E. Brief mit U. Bad Harzburg,..... 1 Seite auf Doppelblatt. 8°". An einen namentlich nicht genannten Adressaten, wohl Martin Flaum in Berlin. KOTTE Autographs GmbH, Rosshaupten. 29 September 1909. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ Ricarda Octavia Huch; Richard Huch (1998). Kommentar zu den Seiten 531-535. Wallstein Verlag. p. 801. ISBN 978-3-89244-184-7.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Georg Ruppelt (9 April 2019). "Das Kleine Wolfenbüttel war eine "Beamtenstadt"". FUNKE Medien Niedersachsen GmbH (Wolfenbütteler Zeitung), Braunschweig. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ a b "Rudolf Huch .... Pseudonym: A. Schuster". Literatur – Mitglieder. Akademie der Künste, Berlin. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ Rudolf von Jhering (author); Rudolf Huch (producer). Der kampf ums recht. Reclams universal bibliothek,nr. 6552, 6553. P. Reclam, Leipzig. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

{{cite book}}:|author1=has generic name (help) - ^ "... Ricarda Huch 1864 – 1947 seit 1926 Mitglied der Abteilung für Dichtung" (PDF). Liste der aus der Akademie der Künste von 1933 – 1938 ausgeschlossenen und ausgetretenen Mitglieder. Akademie der Künste, Berlin. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ Dirk de Klein (compiler) (7 April 2018). "Pledging allegiance to evil-Vow of most faithful allegiance". History of Sorts. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ Rudolf Huch (1934). Israel und wir. Nationaler Verlag J. Garibaldi Huch.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Transkript Buchstabe H, Seiten 154-190". Datenbank: Schrift und Bild: 1900-1960 .... Deutsche Verwaltung für Volksbildung in der sowjetischen Besatzungszone, Liste der auszusondernden Literatur. Berlin: Zentralverlag. 1946. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ "Transkript Buchstabe H, Seiten 104-134". Datenbank: Schrift und Bild: 1900-1960 .... Deutsche Verwaltung für Volksbildung in der sowjetischen Besatzungszone, Liste der auszusondernden Literatur Zweiter Nachtrag, Berlin: Deutscher Zentralverlag, 1948. Berlin: Zentralverlag. 1948. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- 19th-century German male writers

- 20th-century German male writers

- German male essayists

- German male novelists

- Jurists from Lower Saxony

- Corps students

- Heidelberg University alumni

- University of Göttingen alumni

- German satirists

- Nazi Party members

- Writers from Porto Alegre

- Writers from Braunschweig

- 1862 births

- 1943 deaths

- Brazilian emigrants to Germany