Samnite (gladiator type)

A Samnite (Latin Samnis, plural Samnites) was a Roman gladiator who fought with equipment styled on that of a warrior from Samnium: a short sword (gladius), a rectangular shield (scutum), a greave (ocrea), and a helmet. Warriors armed in such a way were the earliest gladiators in the Roman games. They appeared in Rome shortly after the defeat of Samnium in the 4th century BC, apparently adopted from the victory celebrations of Rome's allies in Campania. By arming low-status gladiators in the manner of a defeated foe, Romans mocked the Samnites and appropriated martial elements of their culture.

Samnites were quite popular during the period of Roman Republic. Eventually, other gladiator types joined the roster, such as the Gaul and the Thracian. Under the reign of Emperor Augustus, Samnium became an ally and integral part of the Roman Empire (all Italians had by this point gained Roman citizenship). Around this time, the Samnite gladiator fell out of favour, probably because insulting the Samnites was no longer seen as acceptable behaviour. The Samnite was replaced by similarly armed gladiators, including the hoplomachus and the secutor.

History and role

The Samnite was named for the people of Samnium, an area in the southern Apennine Mountains of the Italian peninsula that Rome subdued in the 4th century BC.[1][2] Rome fought three wars with Samnium from 343 to 290 BC.[3] Livy (9.40) relates that after Rome defeated Samnium and Molise in 308 BC,[4] Rome's allies, the Campanians, confiscated Samnite arms and armour as spoils of war. They outfitted ceremonial warriors with the equipment and staged mock combats at their celebratory banquets:[5][4][6]

The war in Samnium, immediately afterwards, was attended with equal danger and an equally glorious conclusion. The enemy, besides their other warlike preparation, had made their battle-line to glitter with new and splendid arms. There were two corps: the shields of the one were inlaid with gold, of the other with silver … The Romans had already learned of these splendid accountrements, but their generals had taught them that a soldier should be rough to look on, not adorned with gold and silver but putting his trust in iron and courage … The dictator, as decreed by the senate, celebrated a triumph, in which by far the finest show was afforded by the captured armor. So the Romans made use of the splendid armor of their enemies to do honor to the gods; while the Campanians, in consequence of their pride and in hatred of the Samnites, equipped after this fashion the gladiators who furnished them entertainment at their feasts, and bestowed on them the name of Samnites.[7]

Rome's own gladiatorial contests began some 40 years later.[5] The Samnite, borrowed from the Campanians, was the earliest of the gladiator types and the model upon which later classes were based. The Samnite gladiators were also the first of at least three gladiator classes (list of Roman gladiator types) to be based on ethnic antecedents; other examples were the Gauls and the Thracians. These gladiators fought with the signature war equipment and in the martial style of ethnic groups who had been conquered by Rome, thus appropriating their source culture for the mocking milieu of the Roman games.[8] Gladiators who fought as any particular type did not necessarily hail from that ethnic background; the tombstone of a gladiator named Thelyphus is careful to point out that he fought as a Samnite but was really a Thracian.[9]

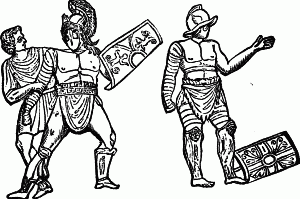

Samnite gladiators appear quite frequently in Roman artwork. Other gladiator classes were added to the roster over the years,[5] and some of these used similar gear, especially plumed helmets, adding to the difficulty of positively identifying Samnites.[10] Roman spectators perceived gladiators as more masculine and honourable if they were more heavily armed and armoured.[11] Thus, the Samnite, one of the heavier types,[12] was an impressive sight with a fierce appearance.[5] The Samnite may have been the first gladiator to be pitted against the retiarius,[13] a gladiator who fought with the gear of a fisherman and who was viewed as effeminate due to his light armaments. Accordingly, some retiarii may have trained as Samnites to improve their status.[14] Gladiators who fought with a rectangular shield and sword, such as the provocator,[15] were said to be "armed in the Samnite manner".[16] Such gladiators remained popular until the end of the gladiatorial games.[5]

Samnite gladiators appear often in Roman texts (they are the gladiators most often mentioned in Roman writings)[17] until the early Imperial period.[18] A likely possibility is that the Samnite went out of favour during the reign of Augustus when Samnium became an ally of Rome.[4] As the real Samnites became fully integrated into Roman society, the gladiator based upon them was retired.[19] At this time, similar classes, the hoplomachus, murmillo, and the secutor first appear in texts.[4][18][20] It seems that the Samnite became specialized into these classes, although the means by which this happened is unclear.[4][21] The Samnite and its successors all fought with a footsoldier's sword and shield.[18] The only clear distinguishing characteristics are that the secutor almost exclusively fought the net-and-trident-wielding retiarius,[10] and the hoplomachus used a taller shield.[18][22]

Arms and armour

Although individual gladiators of a single class might fight with widely different gear,[10] in general, the Samnite fought in the gear of a warrior from Samnium: a short sword (gladius), a rectangular shield (scutum (shield)), a greave (ocrea), and a helmet.[1][10] The helmet had a crest, a rim, a visor, and a plume (galea);[4][17] this last element gave "an imposing appearance". The Samnite's greave was worn on the left leg and reached to just below the knee.[10] It was made of leather and sometimes had a metal rim.[4] He also wore an ankleband on the right ankle.[10] The Samnite's sword arm was protected by an arm guard (manica); this became a common piece of equipment for most gladiators.[23] The sword was the Samnite's most common weapon (the word gladiator comes from the Latin gladius, "sword"),[1] but some seem to have fought with a lance instead.[4]

In addition to this gear, real Samnite warriors wore a cuirass over the chest and had a shield that tapered at the bottom and flared at the top to better protect the chest and shoulders.[10]

Notes

- ^ a b c Baker 12.

- ^ Zoll 114.

- ^ Futrell 4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jacobelli 7.

- ^ a b c d e Baker name="Auguet 77">Auguet 77.

- ^ Kyle 45.

- ^ Livy 9.40, quoted in Futrell 4–5.

- ^ Baker 53.

- ^ Zoll 217.

- ^ a b c d e f g Auguet 77.

- ^ Braund 159.

- ^ Duncan 204.

- ^ Golden 150.

- ^ Baker 56.

- ^ Auguet 80.

- ^ Auguet 215.

- ^ a b Junkelmann 37.

- ^ a b c d Auguet 76.

- ^ Lattuada 108.

- ^ Wiedemann 41 suggests that the murmillo actually derived from the Gaul rather than the Samnite.

- ^ Auguet 76-7.

- ^ Auguet 47.

- ^ Zoll 115.

References

- Auguet, Roland (1994) [1970]. Cruelty and Civilization: The Roman Games. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-10452-1.

- Baker, Alan (2002). The Gladiator: The Secret History of Rome's Warrior Slaves. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81185-5.

- Braund, Susanna Morton (1996). Juvenal: Satires, Book I. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-35667-9.

- Duncan, Anne (2006). Performance and Identity in the Ancient World. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-85282-X.

- Futrell, Alison (2006). The Roman Games. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 1-4051-1568-8.

- Golden, Mark (2004). Sport in the Ancient World from A to Z. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-24881-7.

- Grant, Michael (1995) [1967]. Gladiators. New York: Barnes & Noble Books. ISBN 1-56619-958-1..

- Jacobelli, Luciana (2003). Gladiators at Pompeii. Rome: "L'Erma" di Bretschneider. ISBN 88-8265-249-1.

- Junkelmann, Marcus (2000). "Familia Gladiatoris: The Heroes of the Amphitheatre". In Eckart Köhne, Cornelia Ewigleben & Ralph Jackson (eds.) (ed.). Gladiators and Caesars: The Power of Spectacle in Ancient Rome. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22798-0.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - Kyle, Donald G. (1998). Spectacles of Death in Ancient Rome. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-24842-6.

- Lattuada, Riccardo (2003). "From the Gladiators to Tiger Man: Knowledge, Confrontation, and Death in the Spectacle of the Duel". Gladiators at Pompeii. Rome: "L'Erma" di Bretschneider. ISBN 88-8265-249-1.

- Wiedemann, Thomas (1995) [1992]. Emperors and Gladiators. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-12164-7.

- Zoll, Amy (2002). Gladiatrix: The True Story of History's Unknown Woman Warrior. London: Berkley Boulevard Books. ISBN 0-425-18610-5.