Selma Burke

Selma Burke | |

|---|---|

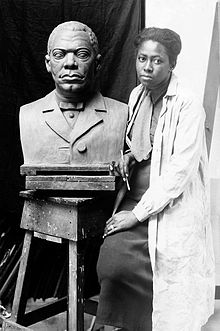

Burke with her portrait bust of Booker T. Washington, c. 1935 | |

| Born | Selma Hortense Burke December 31, 1900 |

| Died | August 29, 1995 (aged 94) |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Columbia University |

| Known for | Sculpture |

Selma Hortense Burke (December 31, 1900 – August 29, 1995) was an American sculptor. She educated others in her passion of art, she founded two art schools, one in New York City and another in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Her art is on display in Washington D.C and North Carolina. She did the bust of Duke Ellington, portraits of Mary McLeod Bethune and Booker T. Washington, and sculptures of John Brown (abolitionist) and President Calvin Coolidge.[1] Burke is best known for her bas relief of President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Biography

Born on December 31, 1900 in Mooresville, North Carolina to a farming family. She was the seventh of ten children of Neal and Mary Elizabeth Burke. Her interest in sculpting was ignited by her maternal grandmother who was a painter.[2] Her father was an AME Church Zion Minister, she demonstrated an early interest in art, but her mother thought she should pursue a more marketable vocation.[3][4] However, her farther nurtured her interests by bringing home souvenirs and art objects from his international travels in Europe, Africa, and the Caribbean as an ocean liner chef.[2] Burke attended a one-room segregated school with a roof that was so leaky she had to protect her books using an umbrella.[1] She graduated from the St. Agnes Training School for Nurses in Raleigh in 1924 and earned a doctorate in arts and letters from Livingstone College in 1970.[1][5] She then moved to Harlem, where she found work as a nurse.

Burke was caught up in the Harlem Renaissance with Claude McKay and, influenced by the Harlem Community Art Center, began to chase her dream of being an artist.[6] Burke continued sculpting in her free time. The Rosenwald (1935) and the Boehler (1936) Foundation Grants[7] in the late 1930s enabled her to study sculpture in Vienna and with Aristide Maillol in Paris, culminating in her Master of Fine Arts degree from Columbia University in 1941.[8]

Burke was chosen to sculpt a portrait of then-President Franklin D. Roosevelt honoring the Four Freedoms.[9] Completed in 1944, the 3.5-by-2.5-foot plaque was unveiled in September 1945 at the Recorder of Deeds Building in Washington, D.C., where it still hangs today.[10] Some have suggested that the plaque may have served as John R. Sinnock's inspiration for his obverse design on the Roosevelt dime.[10] Sinnock, however, denied this vehemently, claiming the design for the dime was based on earlier medals he had sculpted in 1933 and 1934 as well as photographs of FDR.[11][12]

She was committed to teaching art to others; to that end she established the Selma Burke Art School in New York City and opened the Selma Burke Art Center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.[13] Open from 1968 to 1981, the center "was an original art center that played an integral role in the Pittsburgh art community," offering courses ranging from studio workshops to puppetry classes.[10] Burke also taught art in the Pittsburgh Public Schools for 17 years.

Retirement and death

Art didn't start black or white, it just started. There have been too many labels in this world: Nigger, Negro, Colored, Black, African-American... Why do we still label people with everything except "children of God"? - Selma Burke, 1994[14]

Burke retired to New Hope, Pennsylvania and died in 1995, at age 94.

Honors

Burke is an honorary member of Delta Sigma Theta sorority.[8] She received her second doctorate degree at Livingston College in 1970, she also received 8 honorary doctorate degrees for her life time efforts.[7] In 1975, the Governor of Pennsylvania, Milton Shapp, declared July 29 Selma Burke Day in recognition of the artist's enormous contributions to art and education.[15] In 1979 President Jimmy Carter honored Burke at the White House for her contributions to visual arts, praising her as a “shining beacon” for aspiring artists. She received a Candace Award from the National Coalition of 100 Black Women in 1983.[16]

Selected work

- At the age of 80, in 1980, Burke produced her last monumental work, a statue of Martin Luther King Jr. that graces Marshall Park in Charlotte, North Carolina.

Other of her works can be found at:[17]

- James A. Michener Art Museum, Doylestown, Pennsylvania

- Smithsonian American Art Museum

- Greenville County Museum of Art, Greenville, South Carolina

- Habitat for Humanity-Crestdale, Matthews, North Carolina

- Spelman College, Atlanta, Georgia

- Atlanta University, Atlanta, Georgia

- New York Public Library, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York, New York

- Hill House Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

References

- ^ a b c Wallace, Andy (September 1, 1995). "Seattle Times". Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- ^ a b Kirschke, Amy (2014). Women Artists of the Harlem Renaissance. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. p. 119.

- ^ "Dr. Selma Burke". October Gallery. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- ^ "Dr. Selma Burke". Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- ^ Mack, Felicia. "Burke, Selma Hortense (1900-1995)". Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- ^ Verderame, Lori. "The Sculptural Legacy Of Selma Burke, 1700-1995". Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- ^ a b Herring, Mac. "Dr. Selma Burke". Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- ^ a b "Dr. Selma Burke: A Gifted Artist with Many Accomplishments with". African American Registry. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- ^ "Selma Burke; Sculptor, 94". The New York Times. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- ^ a b c Verderame, Lori. "The Sculptural Legacy Of Selma Burke, 1900-1995". Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- ^ Yanchunas, Dom. "The Roosevelt Dime at 60." COINage Magazine, February 2006.

- ^ "John R. Sinnock, Coin Designer". The Numismatic Scrapbook Magazine: pg. 261. March 15, 1946.

{{cite journal}}:|page=has extra text (help) - ^ Stahl, Joan. "Selma Burke". Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- ^ Farris, Phoebe. Women Artists of Color: A Bio-critical Sourcebook to 20th Century Artists in the Americas. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1999. Print.

- ^ Gumbo Ya Ya: Anthology of Contemporary African-American Women Artists. New York: Midmarch Arts Press. 1995. p. 29.

- ^ "Candace Award Recipients 1982-1990, Page 1". National Coalition of 100 Black Women. Archived from the original on March 14, 2003.

- ^ "SIRIS - Smithsonian Institution Research Information System". si.edu. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

External links

- Entry for Selma Burke on the Union List of Artist Names

- Selma Burke's entry on the African-American Registry

- October Gallery

- Kennedy Center biography of Selma Burke

- Long Island University biography

- 1900 births

- 1995 deaths

- People from Mooresville, North Carolina

- Artists from Pittsburgh

- African-American artists

- American women sculptors

- Artists from North Carolina

- Columbia University School of the Arts alumni

- Delta Sigma Theta members

- 20th-century American sculptors

- 20th-century women artists

- Federal Art Project artists