Solid oxygen

Solid oxygen forms at normal atmospheric pressure at a temperature below 54.36 K (−218.79 °C, −361.82 °F). Solid oxygen O2, like liquid oxygen, is a clear substance with a light sky-blue color caused by absorption in the red (by contrast with the blue color of the sky, which is due to Rayleigh scattering of blue light).

Oxygen molecules have attracted attention because of the relationship between the molecular magnetization and crystal structures, electronic structures, and superconductivity. Oxygen is the only one of the simple diatomic molecules (and one of the few molecules in general) to carry a magnetic moment.[1] This makes solid oxygen particularly interesting, as it is considered a 'spin-controlled' crystal[1] that displays unusual magnetic order.[2] At very high pressures, solid oxygen changes from an insulating to a metallic state;[3] and at very low temperatures, it even transforms to a superconducting state.[4] Structural investigations of solid oxygen began in the 1920s and, at present, six distinct crystallographic phases are established unambiguously.[1]

Phase transitions

A total of 6 different phases of solid oxygen are known to exist:[1][5]

- α-phase: light blue - forms at 1 atm below -249.35°C, monoclinic crystal structure.

- β-phase: faint blue to pink - forms at 1 atm below -229.35°C, rhombohedral crystal structure, (at room temperature and high pressure begins transformation to tetraoxygen).

- γ-phase: faint blue - forms at 1 atm below -218.79°C, cubic crystal structure.

- δ-phase: orange — forms at room temperature by applying a pressure of 9 GPa

- ε-phase: dark-red to black — forms at room temperature at pressures greater than 10 GPa

- ζ-phase: metallic — forms at pressures greater than 96 GPa

It has been known that oxygen is solidified into a state called the β-phase at room temperature by applying pressure, and with further increasing pressure, the β-phase undergoes phase transitions to the δ-phase at 9 GPa and the ε-phase at 10 GPa; and, due to the increase in molecular interactions, the color of the β-phase changes to pink, orange, then red (the stable octaoxygen phase), and the red color further darkens to black with increasing pressure. It was found that a metallic ζ-phase appears at 96 GPa when ε-phase oxygen is further compressed.[5]

Red oxygen

As the pressure of oxygen at room temperature is increased through 10 GPa, it undergoes a dramatic phase transition to a different allotrope. Its volume decreases significantly,[6] and it changes color from blue to deep red.[7] This ε-phase was discovered in 1979, but the structure has been unclear. Based on its infrared absorption spectrum, researchers assumed in 1999 that this phase consists of O

4 molecules in a crystal lattice.[8] However, in 2006, it was shown by X-ray crystallography that this stable phase known as ε oxygen or red oxygen is in fact O

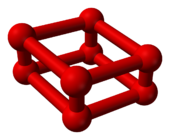

8.[9][10] Nobody had predicted the structure theoretically:[5] a rhomboid O

8 cluster[11] consisting of four O

2 molecules.

|

|

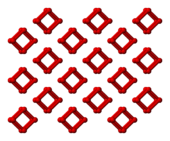

Of all the phases of solid oxygen, this phase is particularly intriguing: it exhibits a dark-red color, very strong infrared absorption, and a magnetic collapse.[1] It is also stable over a very large pressure domain and has been the subject of numerous X-ray diffraction, spectroscopic and theoretical studies. It has been shown to have a monoclinic C2/m symmetry and its infrared absorption behaviour was attributed to the association of oxygen molecules into larger units.

- Liquid oxygen is already used as an oxidant in rockets, and it has been speculated that red oxygen could make an even better oxidant, because of its higher energy density.[12]

- Researchers think that this structure may greatly influence the structural investigation of elements.[5]

- It is the phase that forms above 600 K at pressures greater than 17 GPa.[5]

- At 11 GPa, the intra-cluster bond length of the O

8 cluster is 0.234 nm, and the inter-cluster distance is 0.266 nm. (For comparison, the intra-molecular bond length of the oxygen molecule O

2 is 0.120 nm.)[5] - The formation mechanism of the O

8 cluster found in the work is not clear yet, and the researchers think that the charge transfer between oxygen molecules or the magnetic moment of oxygen molecules has a significant role in the formation.[5]

Metallic oxygen

It was found that a ζ-phase appears at 96 GPa when ε-phase oxygen is further compressed.[6] This phase was discovered in 1990 by pressurizing oxygen to 132 GPa.[3] The ζ-phase with metallic cluster[13] has been known to exhibit superconductivity at low temperature.[4][5]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e

Freiman, Y. A. & Jodl, H. J. (2004). "Solid oxygen". Phys. Rep. 401: 1–228. doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2004.06.002.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Goncharenko, I. N., Makarova, O. L. & Ulivi, L. (2004). "Direct determination of the magnetic structure of the delta phase of oxygen". Phys. Rev. Lett. 93: 055502. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.055502.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b

Desgreniers, S., Vohra, Y. K. & Ruoff, A. L. (1990). "Optical response of very high density solid oxygen to 132 GPa". J. Phys. Chem. 94: 1117–1122. doi:10.1021/j100366a020.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b

Shimizu, K., Suhara, K., Ikumo, M., Eremets, M. I. & Amaya, K. (1998). "Superconductivity in oxygen". Nature. 393: 767–769. doi:10.1038/31656.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h "Solid Oxygen ε-Phase Crystal Structure Determined Along With The Discovery of a Red Oxygen O8 Cluster". Retrieved 2008-01-10.

- ^ a b Akahama, Yuichi (1995). "New High-Pressure Structural Transition of Oxygen at 96 GPa Associated with Metallization in a Molecular Solid" (abstract). Physical Review Letters. 74 (23): 4690–4694. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.74.4690.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Nicol, Malcolm (1979). "Oxygen Phase Equilibria near 298 K". Chemical Physics Letters. 68 (1): 49–52. doi:10.1016/0009-2614(79)80066-4.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Gorelli, Federico A. (1999). "The ε Phase of Solid Oxygen: Evidence of an O4 Molecule Lattice" (abstract). Physical Review Letters. 83 (20): 4093–4096. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.83.4093.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hiroshi Fujihisa, Yuichi Akahama, Haruki Kawamura, Yasuo Ohishi, Osamu Shimomura, Hiroshi Yamawaki, Mami Sakashita, Yoshito Gotoh, Satoshi Takeya, and Kazumasa Honda (2006-08-26). "O8 Cluster Structure of the Epsilon Phase of Solid Oxygen". Phys. Rev. Lett. 97: 085503. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.085503. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lars F. Lundegaard, Gunnar Weck, Malcolm I. McMahon, Serge Desgreniers and Paul Loubeyre (2006-09-14). "Observation of an O8 molecular lattice in the phase of solid oxygen". Nature. 443: 201–204. doi:10.1038/nature05174. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Steudel, Ralf (2007). "Dark-Red O8 Molecules in Solid Oxygen: Rhomboid Clusters, Not S8-Like Rings". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 46 (11): 1768–1771. doi:10.1002/anie.200604410. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|published=ignored (help) - ^ Ball, Phillip (16 November 2001). "New form of oxygen found". Nature News. Retrieved 2006-07-13.

- ^ Peter P. Edwards, Friedrich Hensel (2002). "Metallic Oxygen". ChemPhysChem. 3 (1). Weinheim, Germany: WILEY-VCH-Verlag: 53–56. doi:10.1002/1439-7641(20020118)3:1<53::AID-CPHC53>3.0.CO;2-2. Retrieved 2008-01-08.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|published=ignored (help)