The Monks of Malabar

| The Monks of Malabar | |

|---|---|

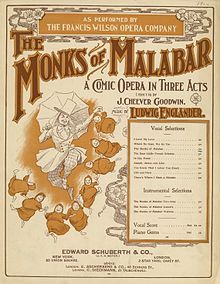

Original 1900 Sheet Music | |

| Music | Ludwig Englander |

| Lyrics | J. Cheever Goodwin |

| Book | Francis Wilson, J. Cheever Goodwin |

| Productions | 1900 Knickerbocker Theatre |

The Monks of Malabar is a "comic opera" or operetta in 3 acts composed by Ludwig Englander with lyrics by J. Cheever Goodwin and book by Francis Wilson (uncredited) and Goodwin. It opened at the Knickerbocker Theatre on 13 September 1900 and closed on 20 October after 39 performances.[1] For its Broadway production, the scenery was designed by Henry E. Hoyt, costumes were designed by Dazian (costumes worn by Miss Lessing furnished by B. Altman and Company), shoes furnished by Cammeyer. The music director and conductor was Emerico Morealle.

Background

By the early 1890s, Francis Wilson had already developed a reputation as being an expert comedian. However in the years prior to 1900, Wilson had experienced a few unsuccessful shows. He appeared in a burlesque of Cyrano De Bergerac in September 1899 in which he played the title character. It was not well received and closed in less than a month.

Already in 1897, he completed an early version of a story he called Bouloo Boulboom in which he would play the title character in broad comic style to show off his comic talents.[2] The completed first draft of the manuscript is dated November 23, 1897. The following year he lent it to J. Cheever Goodwin, who made alterations and wrote lyrics.[3] Rather than repeat the failure of his previous plays such as the burlesque on Cyrano, Wilson set his story in an exotic location, providing many opportunities for broad characterizations and attractive settings.[4] By the time of the first performance, the title was changed to the more recognizable Monks of Malabar. Credits for the play always listed J. Cheever Goodwin as the author; there was no mention of Wilson's authorship with the exception of his ad libbing from the stage.

Plot

Act 1: Under the Taj-Mahal in Malabar. Boolboom has fled from France to India to escape the vixenish temper of Anita Tivoli to whom he was engaged to be married. As the story opens, Boolboom has prospered as a merchant in ivory and is about to wed a native woman Tata-Lilli ("Hail the Groom, Hail the Bride"). Cocodilla enters and speaks about a wife's obligation to her husband ("Where He Goes, We Go Too"). Boolboom and the monks of Malabar confirm the customs ("The Monks of Malabar"), although Boolboom is not beyond flirting with Daru ("The Dear Little French Grisette"). Anita then puts in a very unexpected and unwelcome appearance ("In Gay Paree"). She obliges Boolboom to wed her ("Joseph, James and John"), but he determines to avail himself of "Article 213" should Anita's temper again become unbearable. Article 213 is an East Indian law obliging a woman to be burnt within 24 hours of when her husband dies. The act ends with Boolboom marrying Anita ("Go On and Marry!").

Act 2: Inside the Maharajah's Palace of Pearls. People await the arrival of the Maharajah ("With Keen Anticipate"). He enters and describes his beneficent ruling ("Hear! Hear!"). Zizibar confess her/his deep love for Cocodilla ("You Know That I Adore You"). With Anita proving incorrigible, Boolboom plans to feigns his death ("From Very Earliest Infancy"). To prevent Anita being burnt, Boolboom writes to his friend the Nabob of Malabar, asking him to sees that she gets safely away to France. The Nabob, being in love with Anita, does not carry out Boolboom's wishes ("On My Trim Built Craft"). Boolboom argues ("Then, If I Understand Right") and leaves to feign his death by having been devoured by tigers. The Nabob rescues Anita en route to the funeral pyre, hoping that her gratitude will turn into love ("No More Weighted Down By Sorrow" - Act 2 finale).

Act 3: Inside the Maharajah's Palace of Domes. Zizibar, Cocodilla, Zoloe and Djelma summarize the turn of events ("Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha!"). The servants present themselves to the Nabob for inspection ("Here We Are Sir"). Boolboom returns disguised as a monk but is surprised to find Anita not just alive but now being courted by the Nabob. He disguises himself again as a servant in order to separate Anita from the Nabob ("You assert that you adore me"). Additionally, Boolboom inspires the women to revolt against Article 213. He is so successful that he induces the Maharajah to sell Anita to the highest bidder. He makes a great struggle to purchase her, but is outbid by the Nabob. After much difficulty, he succeeds in rescuing Anita, and gets safely back to France with her ("Finale act 3").

Reception

Criticism leveled at The Monks of Malabar ranged from muted appreciation to distaste. William Raymond Sill wrote in the New York Evening World: "Theatrical history will probably record "The Monks of Malabar" as a qualified success. It is one of those affairs insufficiently bad to be wholly condemned and insufficiently good to be wholly praised. As presented at the Knockerbocker Theatre last night it struck me as being absolutely nebulous. I have reason to consider my premises well taken."[5]

All reviews found the acting of the headliner, Francis Wilson, to be the operetta's most rewarding aspect.

Most reviewers found Englander's music acceptable but not very original:

"Mr. Englander's music, while often trivial, has a certain amount of sparkle and a good deal of rhythmic swing; it is more than a credible achievement, especially when one considers the text to which it had to be fitted."[6]

Ludwig Englander has not aimed directly at either art or originality, but he has touched the one and arrived at the other in several of his numbers. His music is tasteful, melodious and vivacious. The orchestration is remarkable in skill and the whole matter is spirited.[7]

"In the music he has written for the piece, Mr. Englander has been uncommonly successful and has developed a certain brightness, lightness and sparkle that none of his previous music would have led one to suspect him capable of. Mr. Englander has always been one of the most strenuous advocates of the bass drum, and, like all ardent partisans, has rather overworked that honorable instrument. In this last piece, he has restrained himself nobly, and although at times he makes "the little old man in the tinshop": work very hard, he gives him many breathing spells.[2]

"Mr. Englander was not moved by a high ambition when he wrote this score. He was trying to make his tunes to fit his words and he succeeded. There are some numbers which have clearly marked rhythmic effects, and most of them have very familiar melodic foundations. They may serve to please those who do not like anything too new in the musical line."[8]

"Mr. Englander's music is far superior to Mr. Goodwin's book. It is full of melody and rhythm, and some of the numbers--notably the finales--are well built and well adorned in the orchestration. Mr. Englander's music is far superior to Mr. Goodwin's book. It is full of melody and rhythm, and some of the numbers--notably the finales--are well built and well adorned in the orcehstration. One of the songs, "Joseph, James and John" is of sufficient musical attractiveness to make its popularity probable.[9]

The play came in for harsh reviews:

"Mr. Goodwin can write dialogue and lyrics of this type about as well as any other hack writer of librettos, and it may be said that the talk and the verses of the songs in the new book are made in the old familiar way. It may also be said that neither the man about town nor the authors of the best of our short stories will be deeply moved by this book. The intellectual lower middle classes may be amused by it, and if there are enough of them, Mr. Wilson may make money. But it is probably that his harvest will be in countries less near the centres of civilization than New York. The plot of the operetta is not bad, but it fails to develop the expected hilarity, and except for a few humorous lines of Mr. Wilson's own, there is not much to laugh at.[8]

"The Monks of Malabar is as light as a toy balloon, and as a means of diversion it is no less childish. The operetta floats along as blithely and it is as pleasing in color as the toy balloon, but it has not its symmetry. In construction the libretto is pitifully crude. There is not a well devised entrance for any one of the characters, and the single attempt at a dramatic situation is made in the third act...The plot is so well hidden that if one attempts to follow it he misses the attractive features of the extraneous detail. There is little food for laughter in the complications of the story as it is set forth, and the only humor to bge detedcted lies in the individual lines...The desert wastes of dialogue were occasionally broken by musical numbers that were, in the main, very pleasing; and the tediousness of the performance was relieved somewhat by the charming spectacle presented by the scenery and costumes."[9]

Original Broadway cast

- Boolboom, a merchant of Malabar — Francis Wilson

- Daru, nabob of Khari-Khali — Van Rensselaer Wheeler

- The Maharajah of Malabar — Hallen Mostyn

- Bitoby, the nabob's chum — H. Arling

- Bakari, the nabob's chum — Sidney Jarvis

- Macassar, the nabob's chum — J. Ratliff

- Anita Tivoli, a Parisienne — Madge Lessing

- Cocodilla, a lady's maid — Maud Hollins

- Zizibar, her lover — Edith Bradford

- Djelma, Boolboom's servant — Clara Palmer

- Ninika, Boolboom's servant — Louise Lawton

- Zoloe, Boolboom's servant — Edith Hutchins

- also: monks, nobles, bayaderes, guards, citizens of Malabar, slaves, etc.

Post-Broadway

Following its Broadway run, the show went on tour. It was in Boston by November 1900, Philadelphia by December 1900, Cleveland at the start of February 1901, Chicago during the latter half of February 1901, and returned to Boston during May 1901.[10]

Notes

- ^ Although IBDB.com says it opened on 14 September, the New York Times and an original program indicate the date of the first performance was Thursday, 13 September.

- ^ a b "Music and Opera", Clipping File, Billy Rose Theatre Division. Cite error: The named reference "mus" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Wilson's original handwritten script (with date of completion and date mailed to Goodwin) is in Box 8, Francis Wilson Papers, Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

- ^ "Francis Wilson in a New Opera," unidentified newspaper, Clipping Files, Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. The manuscript vocal score also carries this title.

- ^ William Raymond Sill, "Wilson Clever in 'Monks of Malabar'; Englander music too ambitious," New York Evening World (14 September 1900).

- ^ Samuel Swift, "The Monks of Malabar," New York Evening Mail (14 September 1900).

- ^ Untitled review, unidentified newspaper, Clipping File, Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

- ^ a b "Francis Wilson Comes Again: New Operetta Performed at the Knickerbocker Theatre," unidentified newspaper clipping, Clipping File, Billy Rose Theatre Division.

- ^ a b "Knickerbocker--The Monks of Malabar", unidentified magazine review, Clipping File, Billy Rose Theatre Division.

- ^ Information based on programs in the Billy Rose Theatre Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

External links

- The Monks of Malabar at the Internet Broadway Database

- The Monks of Malabar (original performance materials) in the Music Division of The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.