Tobacco in the American colonies

Tobacco cultivation and exports formed an essential component of the American colonial economy during the civil war they were distinct from other cash crops in terms of agricultural demands, trade, slave labor, and plantation culture. Many influential American revolutionaries, including Thomas Jefferson and George Washington, owned tobacco plantations, and were financially devastated by debt to British tobacco merchants shortly before the American Revolution.

Early cultivation

John Rolfe, a colonist from Jamestown, was the first colonist to grow tobacco in America. He arrived in Virginia with tobacco seeds procured on an earlier voyage to Trinidad, and in 1612 he harvested his inaugural crop for sale on the European market.[1] Rolfe’s tobacco operation was an instant boon for American exports.

Chesapeake Consignment System

As the English increasingly used tobacco products, tobacco in the American colonies became significant economic force, especially in the tidewater region surrounding the Chesapeake Bay. Vast plantations were built along the rivers of Virginia, and social/economic systems developed to grow and distribute this cash crop. In 1713, the General Assembly (under the leadership of Governor Alexander Spotswood) passed a Tobacco Act requiring the inspection of all tobacco intended for export or for use as legal tender.[2] In 1730, the Virginia House of Burgesses standardized and improved quality of tobacco exported by establishing the Tobacco Inspection Act of 1730, which required inspectors to grade tobacco at 40 specified locations. Some elements of this system included the importation and employment of slaves to grow crops. Planters filled large hogsheads with tobacco and convied them to inspection warehouses.

The tobacco economy in the colonies was embedded in a cycle of leaf demand, slave labor demand, and global commerce that gave rise to the Chesapeake Consignment System and Tobacco Lords. American tobacco farmers would sell their crop on consignment to merchants in London, which required them to take out loans for farm expenses from London guarantors in exchange for tobacco delivery and sale.[3] Further contracts were negotiated with wholesalers in Charleston or New Orleans to ship the tobacco to London merchants. The loan was then repaid with profits from their sales.

American planters responded to increased European demand by expanding the size and output of their plantations. The number of man-hours needed to sustain larger operations increased, which forced planters to acquire and accommodate additional slave labor. Furthermore, they had to secure larger initial loans from London, which increased pressure to produce a profitable crop and made them more financially vulnerable to natural disasters.[4]

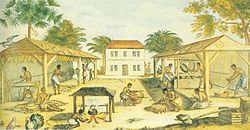

Slave labor on tobacco plantations

Slave boom in the 1700s

The slave population in the Chesapeake increased significantly during the 18th century due to demand for cheap tobacco labor and a dwindling influx of indentured servants willing to migrate from England. In this century, it is estimated that the Chesapeake African slave population increased from 100,000 to 1 million – a majority of the enslaved workforce and about 40% of the total population.[5] Slaves were not imported to the Chesapeake after 1775, but slave populations continued to increase through 1790 because most were forced by their masters to produce large numbers of offspring.

Before the slave boom, Chesapeake tobacco plantations were characterized by a “culture of assimilation”, where white planters worked alongside their black slaves and racial boundaries were less distinct.[5] As slaveholding increased, intense racial contrasts emerged and all-black labor units supervised by white planters came to replace mixed-race units. Unwritten race-based sumptuary laws, which would later become Jim Crow laws, became common social fixtures in Northern and Southern colonies.

For the many farmers who seized opportunity in the profitable tobacco enterprise, financial and personal anxiety mounted amidst stiff competition and falling prices. Some historians believe that these anxieties were redirected onto subordinates in the field, which exacerbated already strained racial relations. Planters pushed slaves to their physical limits to ensure a superior crop. Slaves, meanwhile, realized that the quality of a crop depended on their effort and began “foot dragging”, or collectively slowing their pace in protest of the planters' extreme demands. Farmers racialized foot dragging, portraying it as an inherent personality trait of slaves. William Strickland, a wealthy colonial tobacco planter, remarked:

- “Nothing can be conceived more inert than a slave; his unwilling labour is discovered in every step he takes; he moves not if he can avoid it; if the eyes of the overseer be off him, he sleeps…all is listless inactivity; all motion is evidently compulsory.”[6]

Tensions between slaves and planters occasionally escalated enough to bring work in the field to a standstill. When this occurred, masters often punished insubordinate slaves with physical violence such as lashings and whippings until they resumed their tasks.

Differences between the Chesapeake and Deep South

In the Chesapeake and North Carolina, tobacco constituted a major percentage of the total agricultural output. In the Deep South (mainly Georgia and South Carolina), cotton and rice plantations dominated. Stark diversity in the geographic and social landscapes of these two regions contributed to differences in their respective slave cultures.

The Chesapeake had few urban centers relative to the South. Instead, multiple markets were established along tributaries. This facilitated the persistence of smaller tobacco farms because the cost of moving tobacco to market was kept reasonable. In the south, all economic activity fed through a few heavily centralized markets, which favored large plantations that could bear the higher transportation costs. Differences in plantation size also owed significantly to the different demands of tobacco farming versus cotton and rice. Cotton and rice were cash crops, and cultivation was geared towards maximizing volume. Diminishing returns take effect on harvest quality past a certain threshold of labor investment. Tobacco, however, was considered to be more artisanal and craft-like, with limitless opportunity to improve the yield and quality.[7] Thus, the most profitable cotton and rice operations were large and factory-like, while tobacco profits hinged on skilled, careful, and efficient labor units.

Because of the diminished need for trained labor, families of slaves on cotton and rice plantations would often remain together, bought and sold as complete packages. Individual life expectancies were generally shorter, because their skill set was less refined and workers were easily replaced if killed. Cotton and rice plantation owners employed a management technique called “tasking”, in which each slave would receive around one-half acre of land to tend individually with minimal supervision. The weight of the yield from each slave’s plot was interpreted as a direct reflection of the quality of his work.[8]

In contrast, tobacco planters desired skilled male slaves, while women were mainly responsible for breeding and raising children. Family members were often estranged when women and children left to seek other work. Individual life expectancies for tobacco slaves were generally longer because their unique skills, honed over the course of many years in the field, proved indispensable to a planter’s success. Tobacco planters favored a technique called “ganging”, where groups of eight to twelve slaves worked fields simultaneously under the supervision of a white superior or a tenured slave. The hardest working slaves, called “pace-setters”, were spread amongst the different groups as an example for those around them. Unlike tasking, ganging was amenable to supervision and quality control, and lacked an inherent measure of individual effort.[8]

Some contemporary scholars argue that the Chesapeake was a more hospitable environment for slaves. It was more common in the Chesapeake for a slave to work alongside his master, an arrangement unheard of in the strict vertical hierarchies of massive Southern plantations. Whites and blacks were more deeply divided in the Deep South, and tasking allowed slave owners to arbitrarily replace individuals who did not meet expectations. Others argue that it is disingenuous to romanticize one incarnation of slavery over another and that neither environment was “hospitable” despite these differences.[8]

Colonial tobacco culture

Background

A culture of expertise surrounded tobacco planting. Unlike cotton or rice, cultivating tobacco was seen as an art form, and buyers understood that behind every crop of “good” tobacco was a meticulous planter with exceptional skills. Tobacco shipments were “branded” with a signature unique to its planter before they were sent overseas, and guarantors regarded brands as a seal of approval from the planter himself. One planter proclaimed of his branded tobacco, “it was made on the plantation where I live and therefore as I saw to the whole management of it my self (sic), I can with authority recommend it to be exceedingly good.”[9] Even though not necessarily participating in the manual labor, planters took great financial stake in their final product.

Furthermore, local reputation and social status varied with the quality of one’s leaf. In his book Tobacco Culture, author T.H. Breen writes “quite literally, the quality of a man’s tobacco often served as the measure of the man.”[10] Proficient planters, held in high regard by their peers, often exercised significant political clout in colonial governments. Farmers often spent excess profits on expensive luxury goods from London to indicate to others that their tobacco was selling well. Notably, Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello estate was styled after the dwellings of wealthy European aristocrat.

American Revolution

American tobacco planters, including Jefferson and George Washington, financed their plantations with sizeable loans from London. When tobacco prices dropped precipitously in the 1750s, many plantations struggled to remain financially solvent. Severe debt threatened to unravel colonial power structures and destroy planters’ personal reputations. At his Mount Vernon plantation, Washington saw his liabilities swell to nearly £2000 by the late 1760s.[11] Jefferson, on the verge of losing his own farm, aggressively espoused various conspiracy theories. Though never verified, Jefferson accused London merchants of unfairly depressing tobacco prices and forcing Virginia farmers to take on unsustainable debt loads. In 1786, he remarked:

- “A powerful engine for this [mercantile profiting] was the giving of good prices and credit to the planter till they got him more immersed in debt than he could pay without selling lands or slaves. They then reduced the prices given for his tobacco so that…they never permitted him to clear off his debt.”[10]

The inability to pay what one owed was not just a financial failing, but a moral one. Planters whose operations collapsed were condemned as “sorry farmers” – unable to produce good crops and inept at managing their land, slaves, and assets. Washington excused his situation thusly:

- “Mischance rather than Misconduct hath been the cause of [my debt]…It is but an irksome thing to a free mind to be always hampered in Debt.”[12]

In conjunction with a global financial crisis and growing animosity toward British rule, tobacco interests helped unite disparate colonial players and produced some of the most vocal revolutionaries behind the call for American independence. A spirit of rebellion arose from their claims that insurmountable debts prevented the exercise of basic human freedoms.

See also

References

- Brandt, Allan M. "Pro Bono Publico." The Cigarette Century: the Rise, Fall, and Deadly Persistence of the Product That Defined America. New York: Basic (2009).

- Breen, T. H. Tobacco Culture: the Mentality of the Great Tidewater Planters on the Eve of Revolution. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton UP (1985)

- Goodman, Jordan. ""Wholly Built Upon Smoke"" Tobacco in History: The Cultures of Dependence. London: Routledge (1993).

- Kulikoff, Allan. Tobacco and Slaves: the Development of Southern Cultures in the Chesapeake, 1680-1800. Chapel Hill: Published for the Institute of Early American History and Culture, Williamsburg, Virginia by the University of North Carolina, (1986).

- Morgan, Philip D. Slave Counterpoint: Black Culture in the Eighteenth-century Chesapeake and Lowcountry. Chapel Hill: Published for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, Williamsburg, Virginia, by the University of North Carolina, (1998).

- Rutman, Anita H. "Still Planting the Seeds of Hope: The Recent Literature of the Early Chesapeake Region." The Virginia Magazine Jan. (1987)

Notes

- ^ Brandt, p.20

- ^ http://encyclopediavirginia.org/Spotswood_Alexander_1676-1740#start_entry

- ^ Goodman, p.158

- ^ Brandt, p.23

- ^ a b Kulikoff

- ^ Morgan

- ^ Brandt, p.21-22

- ^ a b c www.digitalhistory.uh.edu Retrieved August 2012

- ^ Rutman, Anita H. "Still Planting the Seeds of Hope: The Recent Literature of the Early Chesapeake Region." The Virginia Magazine Jan. 1987: 3-24. JSTOR. Web. 28 April 2010 Retrieved August 2012

- ^ a b Breen

- ^ Randall, Willard Sterne. George Washington a Life. New York: Henry Holt &, 1998. Print.

- ^ Haworth, Paul Leland. George Washington: Farmer Being an Account of His Home Life and Agricultural Activities,. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1915. Print.