Treaty of Moultrie Creek

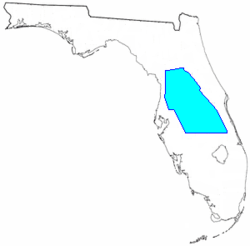

The Treaty of Moultrie Creek was an agreement signed in 1823 between the government of the United States and several chiefs of the Seminole Indians in the present-day state of Florida. The United States had acquired Florida from Spain in 1821 by means of the Adams-Onís Treaty. In 1823 the government decided to settle the Seminoles on a reservation in the central part of the territory. A meeting to negotiate a treaty was scheduled for early September 1823 at Moultrie Creek, south of St. Augustine. About 425 Seminoles attended the meeting, choosing Neamathla, a prominent Mikasuki chief, to be their chief representative. Under the terms of the treaty negotiated there, the Seminoles were forced to place themselves under the protection of the United States and to give up all claim to lands in Florida, in exchange for a reservation of about four million acres (16,000 km²). The reservation would run down the middle of the Florida peninsula from just north of present-day Ocala to a line even with the southern end of Tampa Bay. The boundaries were well inland from both coasts, to prevent contact with traders from Cuba and the Bahamas. Neamathla and five other chiefs, however, were allowed to keep their villages along the Apalachicola River.[1]

Under the Treaty of Moultrie Creek, the United States government was obligated to protect the Seminoles as long as they remained peaceful and law-abiding. The government was supposed to distribute farm implements, cattle and hogs to the Seminoles, compensate them for travel and losses involved in relocating to the reservation, and provide rations for a year, until the Seminoles could plant and harvest new crops. The government was also supposed to pay the tribe US$5,000 a year for twenty years, and provide an interpreter, a school and a blacksmith for the same twenty years. In turn, the Seminoles had to allow roads to be built across the reservation and had to apprehend any runaway slaves or other fugitives and return them to United States jurisdiction.[2]